AEROSPACE Civil aerospace and Covid-19

Creative Destruction 2.0

Covid-19 and the future of the civil aerospace industry

Clockwise from top right: Temperature testing of passengers at Gatwick Airport. (Matt Alexander/PA Wire) 3D printing of medical visor frames at Airbus Spain. (Airbus) EasyJet cabin cleaning. (Ben Queenborough/PinPep) An empty terminal at McCarran Airport in Nevada. (Anthony Citrano)

Clockwise from top right: Temperature testing of passengers at Gatwick Airport. (Matt Alexander/PA Wire) 3D printing of medical visor frames at Airbus Spain. (Airbus) EasyJet cabin cleaning. (Ben Queenborough/PinPep) An empty terminal at McCarran Airport in Nevada. (Anthony Citrano)

Professor KEITH HAYWARD FRAeS analyses how the destructive impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the global aerospace industry may also be a catalyst for revolutionary change and a shake-up of the sector.

Creative destruction was one of Joseph Schumpeter’s most famous ideas: simply put this is the idea of economic renewal through crisis, continually revitalising capitalism by clearing the ground for new forms of wealth creation. A positive force in the long run perhaps but not something necessarily to experience or be on the wrong side of its consequences.

The Covid-19 pandemic may well qualify as a destructive crisis but will it revolutionise the civil aerospace industry? The current dominance of Boeing and Airbus is the result of several decades of drift into oligopoly – an incremental process rather than an abrupt response to a major change in technology or the economic environment. Things might be fundamentally different after the pandemic, but how far are these likely to change the aerospace balance of power? Is this an opportunity for China, or some other well-supported industry to shake the duopoly? It may be too early to judge, perhaps, but well worth some consideration.

A bit of history

The current civil aerospace landscape has a history. Technological innovation has often been a force for ‘creative destruction’ and Schumpeter was one of the first economists to identify technological change as an independent variable in economics. In a far from exclusive list of technological innovations that have shaped civil aviation, there is a pathway from the all-metal, stressed monoplane in the 1930s; the compounded, pressurised airliner of the late 1940s; jet power in the 1950s; computer-authorised control systems in the 1980s; and maybe composite materials, and electric power now coming to maturity. The advent of the high-ratio bypass fan engines in the 1960s might also be added to the list. All of these events helped to shape today’s civil aerospace industry.

Airbus A350 and Boeing 787 at Farnborough Air Show.

Airbus A350 and Boeing 787 at Farnborough Air Show.

Timing (and cash) is all

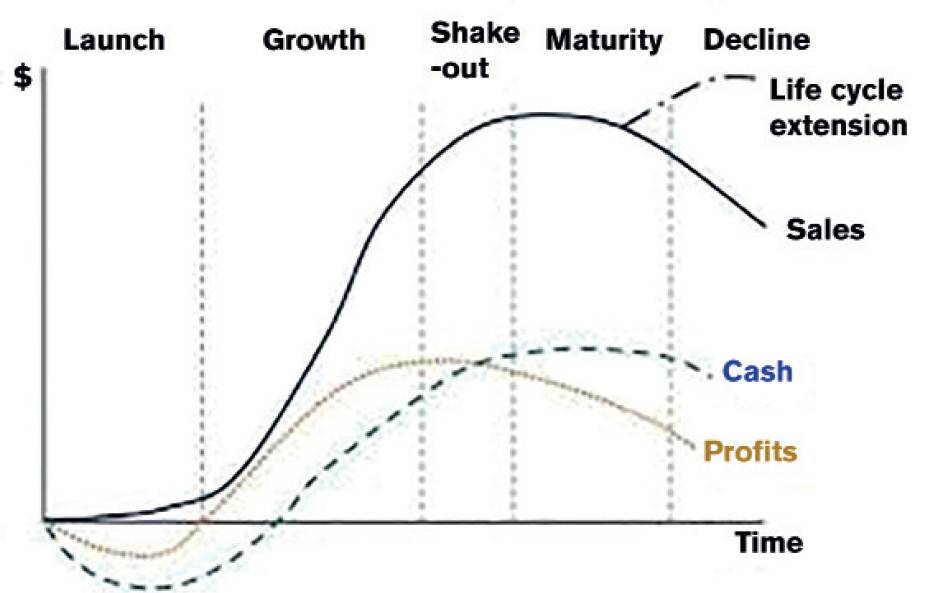

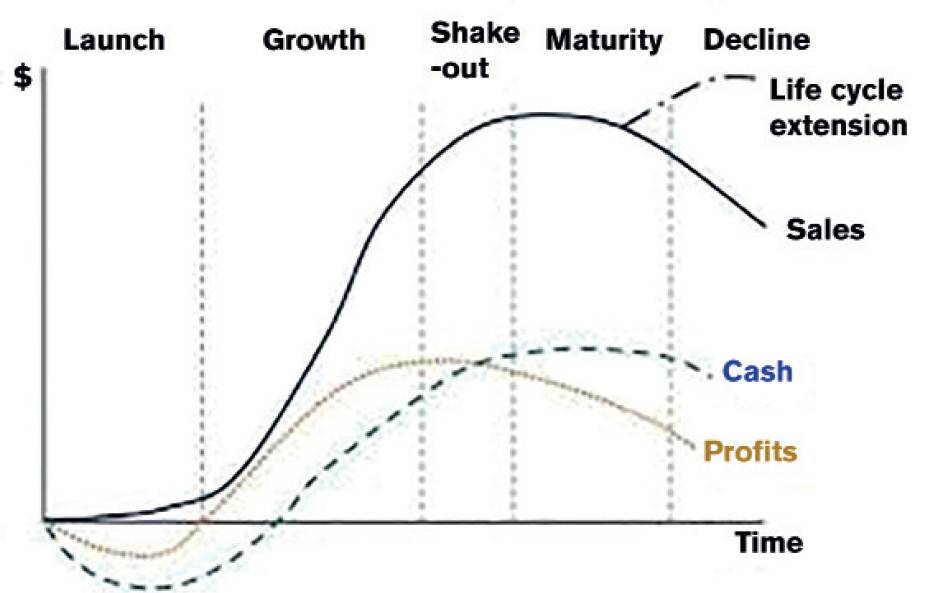

A history of technological innovation does not of itself explain how Airbus and Boeing came to dominate the airliner business. Political economists would immediately look to state funding as either a direct or indirect contributing factor. However, another economic concept, this time the product cycle, coined by Raymond Vernon, might also help our understanding.

The product cycle describes a curve of money over time: first comes the unprofitable initial investment, which puts the curve into a negative quadrant: revenue builds up to put the curve into positive territory: returns build up to a peak, which then begin to decline. Ideally, the positive years are long enough to return the initial investment and profits sufficient to sustain future activity. This may be extended by subsequent smaller investments to renew or upgrade the product but not indefinitely, as competition is almost certainly eroding any early advantage, and which might introduce a superior alternative. The difficult decision is when to initiate a new cycle, which might of course imply a fratricidal effect on the original product’s market.

Oh, but when to take the plunge on a huge new investment, which for a modern airliner is likely to be over $10bn? So it is tempting to keep the old stager going for as long as possible. If this sounds like the Boeing 737 family, and how the 737 MAX debacle may have been one increment too many, the product cycle dilemma is QED. Further back, Douglas had to play catch-up to Boeing when the latter launched the 707 into the market, after Douglas had been reluctant to replace its market leading piston-engined family. Note also a warning for first adopters – de Havilland took advantage of a technological creative destructive moment brought by wartime development of the Whittle turbine with the Comet but could not capitalise on its lead, due primarily to limitations in other technologies and knowledge.

Duopoly is the result of having the cash and good timing

The 737 MAX notwithstanding, and the A380 is probably Airbus’ equivalent failure, commercially if not technically, both Boeing and Airbus have timed new products sufficiently well to stave off credible opposition and in passing to see off established competitors to create their current market dominance (Airbus might also have had some luck in not losing out to the Boeing 787, thanks to faulty battery technology).

A PROTRACTED RECESSION AND DEPRESSED AIRLINER SALES COULD PROVE FATAL FOR MANY IN THE SUPPLY CHAIN.

Without wishing to overload anybody with another economic concept, this has contributed to the ‘high barriers to entry’ in the civil aerospace market. High initial costs, combined with continual R&D ‘learning’, the acquisition of soft skills such as marketing and after-sales service networks, have also encouraged the drift towards duopoly. A similar process has produced an oligopoly in engine manufacturing and other key equipment sectors such as under carriages. State aid somewhere in this process does provide a mighty help in attacking the barriers to entry, but even this is no guarantee that a new entrant can sustain the effort long enough to become a serious contender. And this is a very long-term game remember – it has taken over 50 years for Airbus to reach its current position and for Boeing not far short of 70 years.

In the long run, the duopolists’ power stands and falls on their ability to keep momentum in pushing the product cycle forward, while milking the monetary advantages of an established product range. This is why, all things being equal, the thousands of Airbuses and Boeings on order worldwide, and the imminent threat of innovative additions to the two families, constituted a buttress against new entrants, however, well funded by ambitious governments.

But things may no longer be equal – China lurks

Players still in the game: From top: Boeing’s new 777X-9. Airbus A330-900neo taxiing prior to first flight. Embraer E2 water spray test. Airbus A220s (ex Bombardier CSeries design) under construction in Alabama.

Players still in the game: From top: Boeing’s new 777X-9. Airbus A330-900neo taxiing prior to first flight. Embraer E2 water spray test. Airbus A220s (ex Bombardier CSeries design) under construction in Alabama.

The advent of Covid1-9 and the massive disruption it is causing to the global air transport system may yet be a Schumpeterian moment. For Boeing and Airbus, at almost any other point over the last 20 years, a major recession and its effects might have been less of a challenge (the 2008 financial crisis was one such hiccup) – expensive, yes, but not a realistic opportunity to break the duopoly. China has been knocking on the door for much of this century, but had made little real progress. Now a Covid-induced extended market disruption might just provide China with a breathing space to present a real threat to Boeing and Airbus.

Of course, many countries have tried to break into the civil airliner market – as many as have exited over the years perhaps. Historically, France had one success; Russia never made much of an impact outside its protected national or political markets – and remains a weak player; Germany failed; Indonesia failed; Japan failed. The UK and Holland hung on for a while at the bottom end of the market. Collaboration in Airbus was the eventual route for Europe in general to take on American domination. As the market segmented, Brazil and Canada made a go of it, until Bombardier was swept up into Airbus. Brazil’s Embraer might also have become part of the duopoly and its future may yet be part of a putative ‘creative destruction’ event.

The American and European domination is best explained by reference to a combination the size of their base markets, development of those soft skills mentioned earlier and of course access to some form of state-supported R&D or launch capital. It might also have been relevant that successful civil industries are usually linked to large and technically capable military sectors, either to share the R&D burden or to provide the infrastructure and demand side benefits that increase the scale and scope generally of aerospace activity. This, or its absence, was perhaps a critical reason for Japan’s problems in breaking through in the 1960s, although the FSX national fighter programme at the time was viewed (especially by American critics) as an indirect approach that would spin off into a national civil aerospace industry.

In general, it has been easier to enter and to stay in the regional/feeder airliner market. Three players are still active (excluding Airbus/ Bombardier), Japan, Brazil and China. The latter’s presence depends on the state-pensioner ARJ-21 programme. Moving up from this sector is perhaps the hardest step up the aerospace pyramid; the bigger airliners are technically more challenging, more expensive and require a more sophisticated marketing system to attack a much more demanding set of customers, many of whom like to make package deals across a ‘family’ of products.

China would seem to meet most, if not all of the background conditions to launch a realistic challenge in the 120-seat plus sectors. The country has a large and increasingly capable defence sector supported by heavy national investment to reach regional, if not world super power, status. It has a large and rapidly growing trans-continental economy, evolving under explicit or implicit state intervention and protection. The Chinese economy has achieved a global standing, which will continue to expand after the pandemic. A similarly rapidly expanding national airline industry is subject to political commands to ‘fly the flag’ – the COMAC C919 has 300 orders from Chinese airlines and lessors. Finally, better-placed Western manufacturers have been keen to buy into that market through collaboration – including Airbus’s A320 assembly plant – and offshore sourcing of components.

The now somewhat isolated state of Embraer may provide another option for China. Embraer is a high quality company, with a successful range of products, and an international reputation and market base. This latter feature would be of particular importance for China still struggling to market and support the C919. Although China is not short of engineers and skilled personnel, Embraer’s relatively young and productive workforce was certainly attractive to Boeing, and would be of benefit to COMAC.

Even without the possible addition of Embraer’s civil capabilities, China could lever its advantageous market and financial resources to increase its collaborative range, extracting a higher technical price for its investment. The weaker the current world civil aerospace leadership is post-Covid, the more China might secure from ‘negotiating from strength’, wresting more technology transfer and work share. This might be with the ailing Russian industry but Airbus has more experience of effective and egalitarian collaboration than Boeing. Wider political rivalries might also keep the Americans out.

Technology remains the key to market control

The Product Cycle

The Product Cycle

But let’s not be too quick to dismantle the global airliner duopoly. It is deeply entrenched and China still a long way to go to prove itself a capable civil producer. The C919 150-160 seat airliner, although it has a state-of–the-art Western engine, is a conventional design. Its protracted development also reflects the steep learning curve faced by COMAC as a commercial aerospace systems integrator; and the ChinaRussian widebody project has been delayed due to wrangles between the partners over technology transfers. The duopoly always had the advantage of controlling the location and openness of the technological goalposts, or to apply Vernon’s concept, to time the start of another product cycle. Before Covid, Boeing and Airbus order books were bulging, and despite 737 MAX and A380 setbacks, both were either poised or contemplating innovative products in key market segments. Under normal circumstances, the duopoly might have been content to leave China building an industry based on obsolete concepts, or facing another expensive commitment to stay in touch.

Leapfrogging is another remote and an even more expensive option; Japan sometimes seems to be considering this strategy with second-generation super-, or even hypersonic flight. Well good luck to that; this approach is fraught with huge technical and commercial uncertainties. Meeting the carbonneutral future may provide another entry point, certainly amongst the propulsion community, but the established airframers were also on that case.

However, any significant delay in launching the next investment/product cycle might just provide the strategic opportunity for a new entrant. The loss of two, three, or more years of revenue, underfunding of research activity (which might be mitigated by state intervention) and delays to new launches, might be the point that ‘creative disruption’ hits the market. Boeing has announced a 30% fall in revenue even as the pandemic began to bite and its debt has also risen by $27bn. There is talk of a partnership with Mitsubishi, even as the rites were still being read over the Embraer deal, sunk evidently by Boeing’s financial straits. Boeing has reportedly put off any new launch for five years.

Airbus appears to be in better shape, with a highly liquid financial position, even though its revenues are also down with a ›481m first quarter loss. This is despite ending the A380 and still carrying the cost of A400 development. The acquisition of Bombardier’s CSeries, relabelled as the A220, also seems to have been fortuitous with the market for smaller aircraft promising a quicker recovery. The French government has also been quick to initiate supportive measures. But it too might be pushing new programmes well to the right.

The key question will be just how much spare cash either Boeing or Airbus will have to support expensive new programmes. R&D activity might survive with some reduction in effort, but the real test is when they have to contemplate the large sums needed to launch a new narrowbody or medium-sized airliner.

In addition, moves towards another significant shift in propulsion technology towards electric or hybrid engines are getting more prominence. Green pressures were already pushing strongly in this direction, and investment was rising. Covid-19 has provided another stimulus in the form of government funding designed to help ailing aerospace companies, which have often been linked to carbon neutralising goals. This will afford even more opportunities for new entrants to disrupt established industrial structures.

On their way out – the last of the four-engined passenger aircraft: Left: Due to Covid-19 British Airways has withdrawn its entire fleet of Boeing 747-400s. Production of new 747s is to cease in 2022. Right: A new ANA Airbus A380. Manufacture of the A380 will end next year. British Airways and Airbus

On their way out – the last of the four-engined passenger aircraft: Left: Due to Covid-19 British Airways has withdrawn its entire fleet of Boeing 747-400s. Production of new 747s is to cease in 2022. Right: A new ANA Airbus A380. Manufacture of the A380 will end next year. British Airways and Airbus

A wider disruption in the supply chain?

If it is, in reality, hard to predict outcomes at the top of the civil aerospace pyramid, the supply chain implications are even more problematic. With Airbus and Boeing, along with major OEMs like RollsRoyce, announcing deep production cuts – nearly a third in the case of Airbus – the pain is moving rapidly outwards and downwards. Many suppliers had already been hit by the 737 MAX debacle. Bankruptcy and, in due time, consolidation will affect the supply chain, and not just the weaker firms either, if a company is especially vulnerable to cash-flow issues. The pain is likely to be greater, as many firms had been asked to ramp up to sustain increased rates; some will have over-borrowed on the strength of future revenues.

Among the second tier OEMs there has been a similar structural trend towards, if not duopoly, certainly narrow oligopolies. Below this level, globalisation, driven either by business strategies looking to ‘strategically’ source in order to win market access, political demands for ‘offset’ in some form or another, and good business sense seeking more productive, cost-effective sources, had become the norm.

CHINA WILL BEGIN TO LOOM LARGER AS A POTENTIAL COMPETITOR AND PERMANENT THREAT TO THE ‘BIG TWO’

However, failings in global sourcing had already begun to emerge before Covid. There was evidence of primes and OEMs bringing some aspects of manufacturing ‘in-house’ to ensure greater control over quality and supply. In the case of US-China relations, political tension was again increasingly a feature of supply chain choices. Post-Covid supply disruptions as firms fail, more domestic political demands for national sourcing, and an invariable contraction into national industrial base approaches might apply a salutatory effect on global aerospace supply chains.

And the darkest side of post-Covid disruption – which companies might not survive? Mergers and acquisitions activity has slowed down and, so far, few companies have failed or looked for aid but this might be a lull as reality hits the supply chain. Again, much will depend upon the speed and quality of the upturn. A protracted recession and depressed airliner sales could prove fatal for many in the supply chain.

As one of the key OEMs, Rolls-Royce is already having a torrid pandemic, shedding 9,000 jobs world-wide but especially in its East Midlands heartland. It is asking its suppliers to share the pain and more bad news may yet follow. Suppliers are being asked to slash their prices by 15% or lose Derby’s business.

Rolls-Royce, with much of its civil business tied to long-range widebodies and servicerelated revenues, will not immediately benefit from a revival in short/medium haul traffic and LCC operation. Longer haul traffic is likely to be sticky for some years yet. Although its stock price has slumped, there should not be any alarm bells yet but the UK Government would be advised to check its golden share and a means to make life difficult for potential predators.

A final twist in the saga as far as UK suppliers are concerned (this includes the Airbus wing operation), is the impact of a post-Brexit environment. If EU-located Airbus suppliers see an uptick in repatriated business, there are no guarantees that much of this might come to the UK, especially if a hard Brexit increases overhead and other administrative costs. There is no permanent reason why next-generation wing production should stay in the UK. Unless there is a deal to fix both the future relationship with EASA and retain British access to an increasingly well-funded EU research fund, a postCovid, post-Brexit world looks really tough.

On their way in – the new generation of rivals. Left: Expected to return to the skies – the Boeing 737 MAX. Right: New kid on the block – the COMAC C919. Boeing and COMAC

On their way in – the new generation of rivals. Left: Expected to return to the skies – the Boeing 737 MAX. Right: New kid on the block – the COMAC C919. Boeing and COMAC

Future uncertainties

In the end, only time will tell whether we are entering a new Schumpeterian world. At least one analyst is forecasting that the demand for new aircraft will drop by 50% by 2028, a huge reversal on the growth rates that had underpinned business models throughout the civil aerospace industry for much of the last two decades.

Nevertheless, the Airbus/Boeing duopoly will be hard to dislodge – to reiterate they still have powerful incumbent advantages. Neither are especially exposed to increasingly uncertain global defence markets – Boeing of course has some degree of national defence market protection but a slowdown in defence spending will reverberate throughout the industry, particularly if oil-fuelled customers lose their relish and their ready cash for buying expensive equipment. The market for smaller airliners is likely to pick up quicker than wide-bodies, which again while good for volume cuts into margins. However, Boeing still has to prove the 737 MAX is safe and commercially viable.

However, as someone who once forecast the demise of Airbus in the late 1970s, this is one cautious historian-analyst. The key question will be how long the duopoly has to delay new product/new technology launches. The more protracted that turns out to be, the more China will begin to loom larger as a potential competitor and permanent threat to the ‘Big Two’.

Clockwise from top right: Temperature testing of passengers at Gatwick Airport. (Matt Alexander/PA Wire) 3D printing of medical visor frames at Airbus Spain. (Airbus) EasyJet cabin cleaning. (Ben Queenborough/PinPep) An empty terminal at McCarran Airport in Nevada. (Anthony Citrano)

Clockwise from top right: Temperature testing of passengers at Gatwick Airport. (Matt Alexander/PA Wire) 3D printing of medical visor frames at Airbus Spain. (Airbus) EasyJet cabin cleaning. (Ben Queenborough/PinPep) An empty terminal at McCarran Airport in Nevada. (Anthony Citrano)