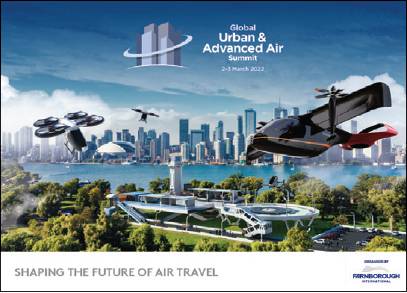

GENERAL AVIATION Global Urban and Advanced Air Summit

Looking at the bigger picture

With the technical development of air mobility eVTOL vehicles now well advanced, attention is turning to the wider infrastructure in which they will operate. BILL READ FRAeS reports from Farnborough on the key issues discussed at the third Global Urban & Advanced Air Summit (GUAAS).

Eve

Eve

On 2-3 March, the Farnborough International Exhibition & Conference Centre hosted the third meeting of the Global Urban & Advanced Air Summit (GUAAS) in which UAM manufacturers met with regulators, government, investors and infrastructure providers to share knowledge and discuss plans for the implementation of the aerial transport systems of the future.

Coming soon to a city near you

At the first meeting of this event in September 2019, then called GUAS (Global Urban Air Summit), speakers predicted that the first commercial flights of urban air mobility (UAM) systems would be operating over cities within two to three years. This year, two to three years later, the speakers at GUAAS (the extra A was added to the acronym to broaden the definition of UAMs beyond just urban transport) told us that the first flights would be operating – within two to three years.

It might be thought that the most obvious reason why the first flights have not yet materialised, has been the two years of the Covid-19 pandemic which paralysed air transport networks around the world.

It might be thought that the most obvious reason why the first flights have not yet materialised, has been the two years of the Covid-19 pandemic which paralysed air transport networks around the world.

However, the onset of Covid has proved to have little effect on the technical development of advanced air mobility (AAM) platforms.

A second virtual version of the conference (GUAS 2.0) held in July 2020, included a number of presentations from UAM manufacturers who were busy continuing the development of their projects, despite the restrictions of Covid lockdowns.

Although AAM technology is maturing fast with several prototype vehicles now being flight-tested, speakers at this year’s GUAAS conference agreed that there are still many challenges to overcome before AAM networks can be created to offer alternative transport systems across or between cities.

Preparing for take-off

Despite the restrictions caused by Covid-19, the past two years have seen huge investments into AAM projects with manufacturers taking great strides in the development of electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) platforms with a number of prototypes now being flight-tested.

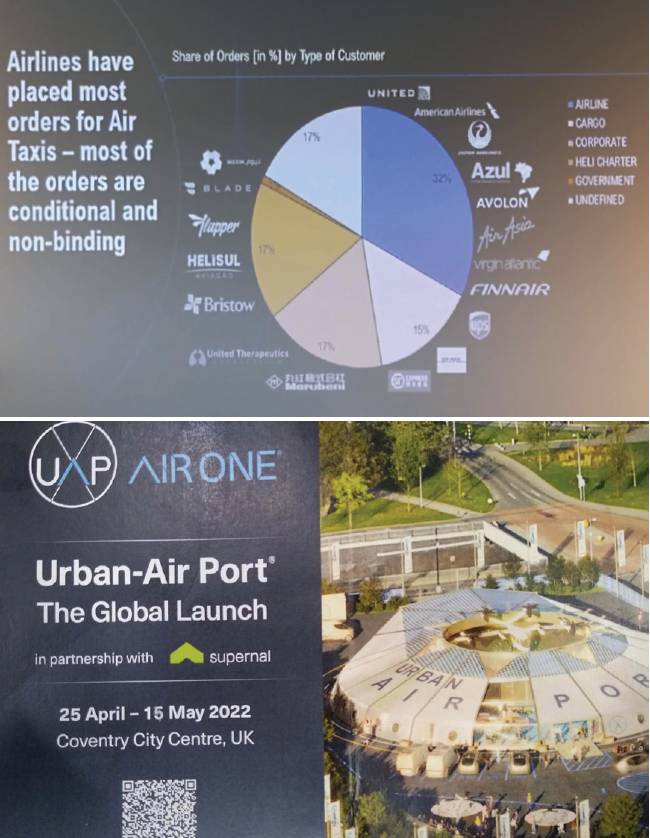

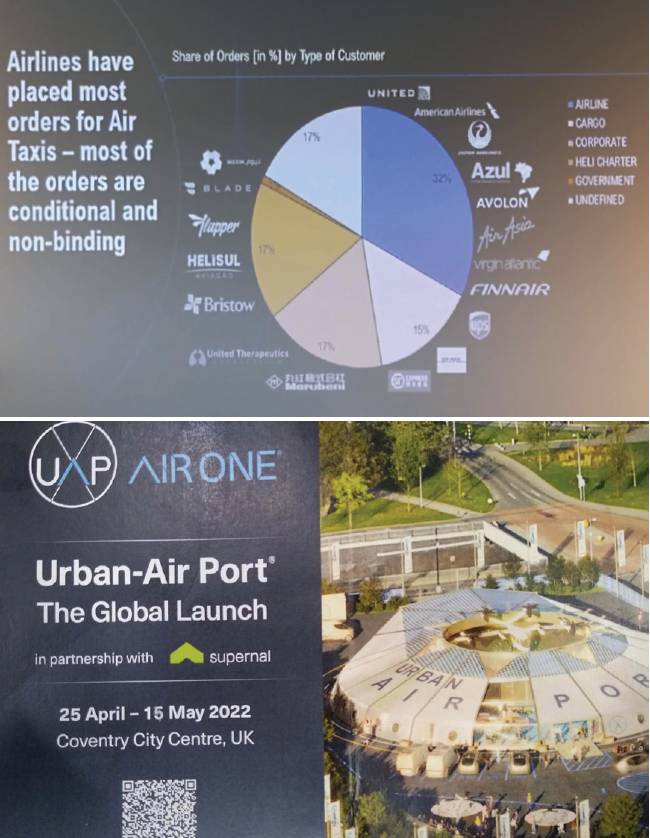

Manfred Hader, Head of Aerospace, at Roland Berger explained how 2021 saw a huge increase in investment into AAM projects totalling $7.535bn – more than is spent by some airlines. Most of this investment was in platforms and cargo applications, although there was now a move towards passenger transport. Hader also added that recent years have seen a number of large commitments for AAMs, many of which have come from airlines.

WHILE PEOPLE WOULD SEE THE ADVANTAGES OF MEDEVAC AND EMERGENCY SERVICE EVTOLS SAVING LIVES IN THEIR COMMUNITY, WOULD THEY BE SO KEEN ON RICH PEOPLE FLYING OVERHEAD IN AERIAL TAXIS THAT NO ONE ELSE COULD AFFORD?

However, while making a flying eVTOL prototype is one achievement for an AAM manufacturer, mass producing thousands of flying vehicles for passenger transport is quite another. To be certificated to carry passengers, AAMs may need to carry additional safety systems, including avionics, transponders, navigation systems, AI systems and even flight recorders.

Each variant will need to be tailored to its operational environment, including hot and cold climates, altitude above sea level, wind conditions, rain, fog and snow. Some AAMs may also need additional hot/cold weather equipment, such as de-icing systems for safe operations in cold weather or air conditioning for passenger comfort in hot weather. All these extra systems will add to weight and reduce payload.

Looking further to the future, Robin Riedel from McKinsey & Co predicted that: “AAMs will need six advances in technology – autonomy, power sources, lightweight materials, distributed electric propulsion, aircraft configuration and smart customer experience.” Matheu Parr, Customer Business Director at Rolls-Royce, said that current battery technology limited the size and range of electric aircraft. To achieve carbon-free travel over longer distances, future operators would have to fly aircraft powered by hybrid gas turbines, fuel cells and hydrogen.

Airbus

Airbus

Who will fly them?

Speakers were agreed that the first AAMs are likely to have to be piloted until such time as regulators are convinced of their safety and remotely piloted, autonomous or multiple platform swarming systems reach sufficient technological maturity to replace them.

“AAMs will initially be piloted but will be ‘autonomous ready’,” said Swanson Aviation Director, Darrell Swanson. “The technology is there but we need time to demonstrate to regulators that autonomy is safe.” Training will be both for pilots and remote pilots and a couple of manufacturers are now looking at AAM flight training simulators.

“AAMs will initially be piloted but will be ‘autonomous ready’,” said Swanson Aviation Director, Darrell Swanson. “The technology is there but we need time to demonstrate to regulators that autonomy is safe.” Training will be both for pilots and remote pilots and a couple of manufacturers are now looking at AAM flight training simulators.

AAM manufacturers are taking different approaches with regard to who operates the passenger-carrying eVTOLs. “We’re going to stick to manufacturing; we’re not trying to be an airline,” said Michael Cervenka from Vertical Aerospace. Volocopter, however, prefers to maintain control of its AAMs by operating them themselves, as the company believes that it is best qualified to fly them safely, rather than relying on a less experienced third party. Joby Aviation plans not only to build and operate its own aircraft but also to design the wider ecosystem in which they operate.

MRO

Many of the practices already used in the air transport industry could also be applied to AAMs – such as predictive maintenance, MRO services, battery management and ground handling operations. Digital technology is expected to take a lead role in this in both aircraft design and operations.

A Skybus across London. Skybus/pascall watson

A Skybus across London. Skybus/pascall watson

Regulators – friends rather than foes

AAM manufacturers are currently moving from the development of prototypes to working with regulators on flight safety certification. Tim Johnson, Policy Director from the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) envisages a dual role for regulators – to supply regulatory approvals and also to create regulatory frameworks to enable innovators to safely come to market. Together with Jay Merkle, Executive Director, UAS Integration Office from the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Johnson explained how the two national regulatory bodies are working together, along with other regulators, to create bilateral safety agreements in which eVTOLS certified by one authority can be validated by another. “Regulators are learning from each other,” he explained.

Looking beyond platforms

Two slides from the conference. RAeS/Bill Read RAeS/Bill Read

Two slides from the conference. RAeS/Bill Read RAeS/Bill Read

Much of the discussion at GUAAS was not about new eVTOL platforms but the wider ‘ecosystem’ which will be needed for them to operate in. No AAM will be able to fly until it has somewhere to take off and to land.

A number of companies are working on designs for vertiports, some next to airports, some on the top of high buildings and some built in new locations. Careful planning is needed to ensure that AAMs can safely operate in and out of these new locations and that they are designed to operate efficiently and are financially viable.

However, the costs of creating this new infrastructure, both physical and air traffic management systems, will not be cheap. Both airports and high-rise buildings in central urban areas will charge high prices for landing fees.

This is likely to result in high prices to use the new air taxis which means that, at least initially until economies of scale are built up, the service will only be affordable to high-value customers.

Flying through urban canyons

Additional research is also needed to study the unique flying environment posed by city infrastructure and how AAMs will navigate through a crowded lower airspace and cope with adverse atmospheric conditions, such as urban canyon crosswinds and invisible vortices.

AAMs, particularly those that operate autonomously, will also need to be resilient against cyber-attacks and jamming devices.

They must also be designed to avoid the risk of signal blackouts due to high buildings blocking GNSS global navigation satellite system line-of-sight communications and the risk of overlapping communications spectrum at lower altitudes.

The conference heard from Starr Ginn, AAM National Campaign Lead at NASA which is working on a number of projects to explore the different challenges that AAMs will have to overcome – including new methods of operations.

AAMs (first piloted and then unpiloted) will have to navigate around moving and fixed obstacles in a complicated and continually changing low-level urban airspace, fly safely through unique air conditions, including urban canyon crosswinds and invisible vortices and use steep approaches to land on top of narrow buildings.

One question also discussed was who should be responsible for the low-level airspace in which the AAMs should operate – the national air navigation service provider, local government or a private air traffic management company.

Uber’s vision of a future vertiport. Uber

Uber’s vision of a future vertiport. Uber

A risky business

A cautionary note was issued by Dr Elmar Giemulla, Professor and Legal Aviation Consultant, Giemulla Associates who stated bluntly that: “Technology kills and this technology will kill. There are air crashes and we accept this. The role of safety regulations are to attempt to reduce this number to the lowest point possible. The disadvantages (ie the death toll) must be outweighed by advantages.”

Other safety risks that might be faced by autonomous AAMs were explained by Steve Vance, Director of UK Aerospace, CGI. There have already been a number of incidents around the world in which drones fell out of the sky due to spectrum interference, including China and Las Vegas where members of the public were hit by drones, as well as a 16kg drone which crashed in Wallsend, Northumberland. Steve Vance explained how it was currently possible for the general public to buy electronic jamming devices which could down drones – even though their actual use was illegal. Military and security services also use jamming devices to down drones which fly close to restricted areas. There were also ‘position spoofers’ which may have been the cause of the Chinese drones falling out of the air during a public display because their navigation systems were fooled into thinking they were in restricted airspace and they landed immediately. Such devices could potentially also be used to take down larger passenger-carrying AAMs operating using autonomous navigation systems

Even without the threat of malicious attacks, there are also risks to AAMs from overlapping spectrum where signals intended for one purpose become mistaken for another – as has recently been in the news in the airport landing systems vs 5G phone signals controversy in the US. Communication systems which rely on line-of-sight can also experience problems in the urban environment where high buildings can block satellite coverage. AAMs need to be built to include redundancy in equipment, such as receivers which are resilient to attack and multiple forms of navigation should there be a loss of signal.

Winning hearts and minds

However, for AAMs to succeed, it is important to have the support of the communities in which they would operate. AAM system developers will have to reassure the public that eVTOLs are safe, quiet and of benefit to the community.

A Joby Aviation prototype eVTOL in flight. Joby Aviation

A Joby Aviation prototype eVTOL in flight. Joby Aviation

To encourage public awareness and acceptability of AAM operations, eVTOLs are expected to follow the same path as drones, in which they were seen to be used for the public good.

Elmar Giemulla cited the example of how, 15 years ago German regulators were not keen on drones but subsequently became more enthusiastic after drones were used in 2021 to help with the Rhine flooding, including flying into houses to look for survivors.

As a result, not only regulators but the German public began to approve of drones. The first AAMs operating in a city could be used in a similar way with pilot projects using them as emergency service vehicles.

However, opinion was divided on whether people would accept the introduction of AAMs.

While people would see the advantages of medevac and emergency service eVTOLs saving lives in their community, would they be so keen on rich people flying overhead in aerial taxis that no one else could afford?

A number of speakers stressed that, for AAM transport systems to succeed, there is a need not just for public acceptance but pro-active enthusiasm.

An interesting suggestion came from Jack Withinshaw, Chief Commercial Officer at flying car manufacturer Airspeeder, who suggested that staging aerial vehicle races could stimulate public interest into the potential of AAMs.

“Consumers love sport,” he stated.

“Air races, such as the Schneider Trophy in the 1920s, were key to popularising flying in the past and could do the same for electric aircraft and AAMs in the future.”

Use cases

The conference also looked at a number of scenarios in which AAMs could be introduced into the transport infrastructure. Hristo Hristov, Manager, Business Development, DRONAMICS explained how his company had looked at a number of potential use cases for AAMs – as a low-cost helicopter replacement, for intercity trunk routes and regional routes of up to 200 miles and as regional starts in the UK, US, China and within Singapore.

Sunil Budhdeo from Coventry City Council gave details of plans for Coventry to become the first UK city to operate an AAM vertiport which he claimed was the solution to reducing congestion and achieving zero-carbon goals.

Sunil Budhdeo from Coventry City Council gave details of plans for Coventry to become the first UK city to operate an AAM vertiport which he claimed was the solution to reducing congestion and achieving zero-carbon goals.

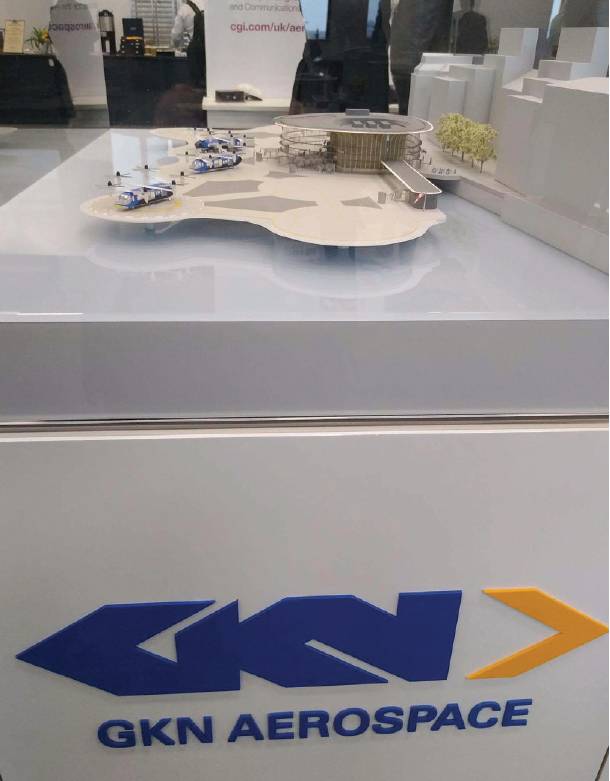

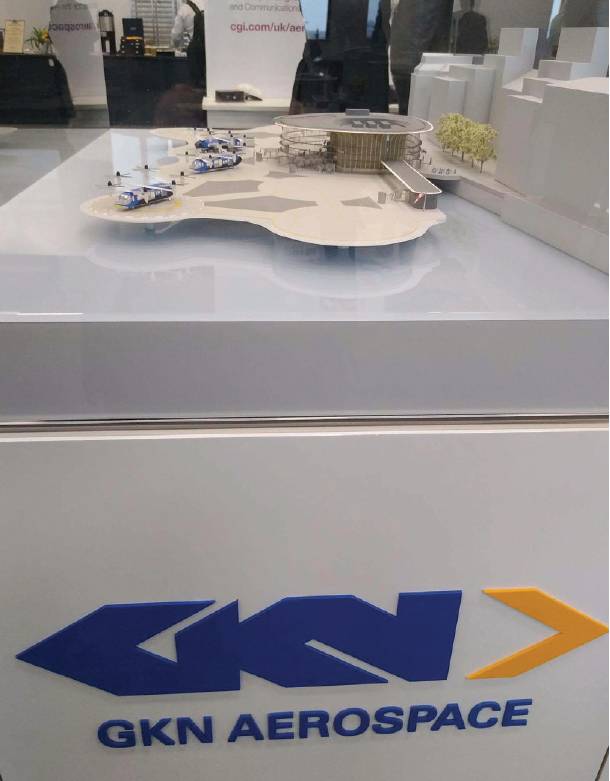

Darrell Swanson, Director, Swanson Aviation described a concept proposal for a Thameside vertiport designed to operate the 30-passenger GKN Skybus eVTOL design.

The proposal covered a large number of different factors to be considered – including provision for lots of landing ramps, space to store eVTOLs on the ground, passenger security, 15min turnaround times, other transport links (including eScooters), stylish appearance and retail opportunities.

Oddly enough, the concept did not seem to include any provision for carrying luggage – a question on this posed by this author at the conference got the reply that passengers would be expected to book their luggage to travel separately on a slower ground-based route.

Conclusion

Progress on introducing AAMs is expected to be slow at first but will quickly build up once the concept is proved successful.

According to Manfred Hader from Roland Berger, there could be as many as 160,000 AAMs operating by 2050 – the majority in Asia and the US.

However, AAM development can only succeed if all interested parties (manufacturers, regulators, investors and local government) work together.

Will the public prove that AAMs will be a benefit to the community?

In the words of Manfred Hader: “People want this to happen: we’re just waiting for things to really fly. The scene is set – it’s becoming more real every day.”

Eve

Eve It might be thought that the most obvious reason why the first flights have not yet materialised, has been the two years of the Covid-19 pandemic which paralysed air transport networks around the world.

It might be thought that the most obvious reason why the first flights have not yet materialised, has been the two years of the Covid-19 pandemic which paralysed air transport networks around the world.