AIR TRANSPORT Female airline instructors

Breaking the flight deck glass ceiling

A new report from the RAeS and the University of the West of England, Bristol looks at why so few airline instructors and type examiners are female and identifies the barriers to career progression for female pilots. BILL READ FRAeS summarises the main conclusions.

Pilots from left to right: Iberia, Lufthansa, British Airways and Air France. (Iberia, Lufthansa,BA, Air France).

Pilots from left to right: Iberia, Lufthansa, British Airways and Air France. (Iberia, Lufthansa,BA, Air France).

In March an independent study, commissioned by the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) and the University of the West of England (UWE), was published which examined why so few pilot trainers are female and what are considered the barriers to career progression for female pilots. According to the International Federation of Airline Pilots (IFALPA), in January 2020 there were 185,143 airline pilots in the world. Of these, 9,746 were women (5.26%) and 2,630 were captains (1.42%) (IFALPA 2021). This percentage has since fallen even further as female pilots were adversely affected by redundancy policies due to Covid-19, resulting in some US airlines seeing their numbers of female pilots dropping from 5.1% to 4.1%.

The RAeS/UWE report, entitled, What is the future for gender diversity in the pilot trainer role? Myth or reality, highlights that, while only around 5% of the global pilot workforce is female, the number taking up training roles is even fewer. According to 2022 statistics from the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), fewer than 0.9% of type rating examiners (TREs) are women.

The study gathered responses from over 700 airline pilots worldwide, 75% of whom were male. Although the report did not specifically ask about sexism, it reported multiple examples of sexism and sexual harassment, with respondents frequently citing an ‘old boys’ network’ and a lack of female role models and mentors.

Becoming a pilot

Before women can be flight trainers, they need first to become pilots, a career which involves both emotional and financial investment. Pilot training is expensive: a basic licence costs around £120,000, while further training on passenger aircraft may cost around £30,000.

Before women can be flight trainers, they need first to become pilots, a career which involves both emotional and financial investment. Pilot training is expensive: a basic licence costs around £120,000, while further training on passenger aircraft may cost around £30,000.

Even having gained a basic qualification, pilots then have to try and find jobs in a highly competitive market. For those women who are pilots, the airline cutbacks due to the Covid pandemic had a disproportionate effect, with 62% of the female pilots in the survey having been furloughed, compared to only 31% of the male respondents.

Over the past six years there have been a number of initiatives to address the lack of female pilots which have focused upon outreach work with young people to dispel the myths surrounding the profession and to support those interested in investing in a pilot career. However, the report says that both women and minority group pilots currently working within the aviation industry say that they are still experiencing discrimination.

Becoming a flight trainer

There is no official career path to become a pilot trainer and recruitment is almost exclusively conducted by internal staff (who are overwhelmingly male) and departments who have no formal industry recommendations with which to work. Men were more likely to know where to find information about their training department recruitment process, be given support and encouragement to apply and, in some cases, invited into the role without a formal interview, unlike women who were generally not actively encouraged, and all went through a formal interview process.

Another reason cited for the scarcity of women in the flight trainer’s role is the requirement by airlines for trainers to work full-time, which has a disproportionate effect on women who have family commitments. Although it has become more acceptable in recent years for pilots to work part-time, this has not yet moved into pilot training, despite a preference from both male and female trainers and pilots for the role to be offered on a more flexible part-time basis.

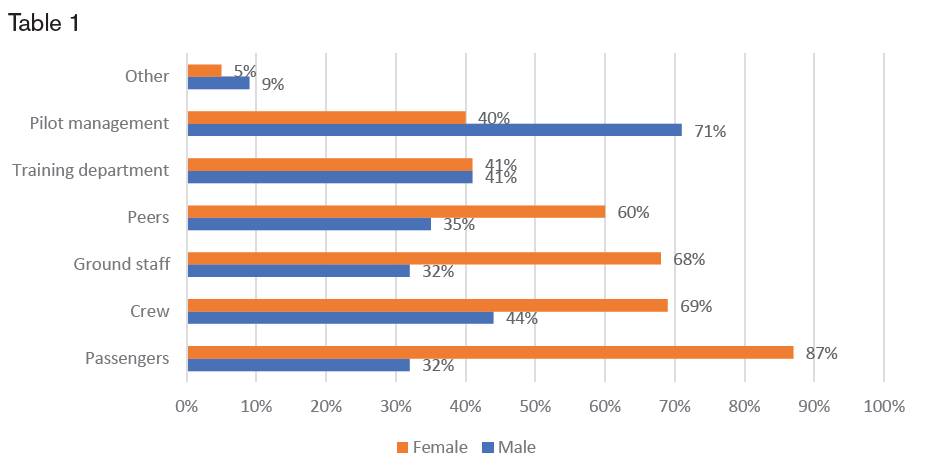

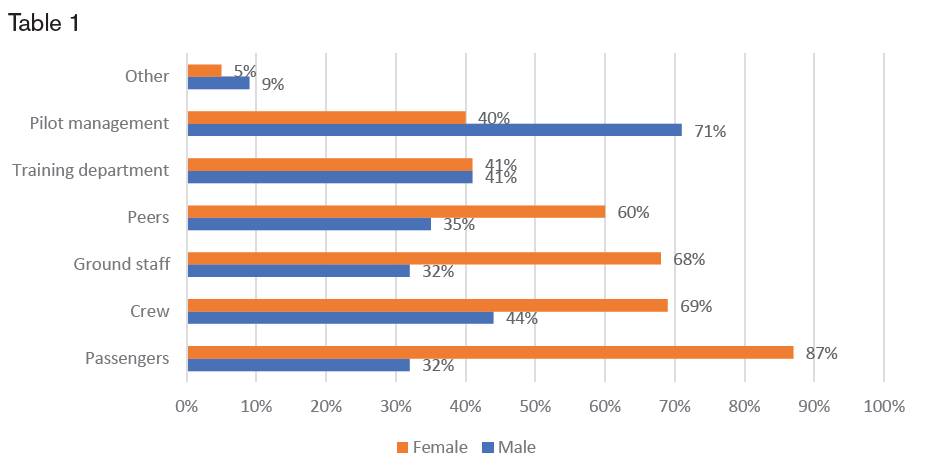

A table showing those who treated women differently because of gender by whom (by gender).

A table showing those who treated women differently because of gender by whom (by gender).

Old boys’ network

However, one of the biggest barriers for women becoming flight trainers is what has been described as a ‘toxic environment’ for women. Many training departments were reported to be run by ex-military men who ‘tended to recruit their own’. Many of the male respondents recognised the presence of the ‘old boys’ network’, with some feeling excluded from it themselves.

The report also quoted multiple examples of incidents in which female pilots and trainers had encountered sexism, sexual harassment and bullying during training. Many of these incidents went unreported by women due to the lack of safe reporting processes in place and a fear of being labelled ‘difficult’. Employers were not perceived as being supportive of women and, in some cases, exacerbated the already challenging situation in which the women found themselves. There were also incidents of sexism from airline passengers towards female pilots.

What can be done?

Some action is already being taken. The CAA recently launched a confidential reporting channel, through the Confidential Human Factors Incident Report Programme (CHIRP) for members of the industry to report bullying, harassment, discrimination and victimisation.

However, the report urges that a more fundamental cultural change is needed. Women need more support from their employers and to be treated with respect by both peers and passengers. Professional and appropriate behaviour is fundamental to the safety of all aircraft.

AIRLINES AND TRAINING COMPANIES SHOULD OFFER TRAINER ROLES ON A PART-TIME BASIS TO BOTH MEN AND WOMEN

Training is the first point of contact for new entrants into the aviation industry and is currently conveying a message that this is a male-dominated career. Training departments are key to the growth and recovery of the airline industry and are essential to the cultural change that needs to occur to make the industry more inclusive. Airlines and training schools have a duty of care towards their employees, as do regulators, who need to be more involved with training organisations to ensure that individuals are safe at work and free from harm.

All trainees (both male and female) need to be educated in appropriate behaviour towards their colleagues. Those in management positions should openly advocate good behaviour and respect to all fellow colleagues and trainees. Organisations should be responsible for ensuring they have adequate reporting processes in place to record negative behaviours and should also encourage a non-punitive reporting culture in the interest of safety.

One suggested way to address these issues is for airlines to become more connected to training delivery. Nearly all airlines outsource initial pilot training, meaning that operators may lose sight of the quality of the training and the opportunity to influence the training culture environment.

Pilot students’ classroom. Swinburn University of Technology

Pilot students’ classroom. Swinburn University of Technology

Role models

Because there are so few female pilot trainers, this means that there are very few role models available. The study stated that the presence of more role models and mentors would also tackle the problem that women were less likely than men to receive support when applying for training and less likely to be made aware of their opportunities early in their careers.

Conclusions

The report had four main conclusions:

- To combat the issues of sexism, sexual harassment and the ‘old boys’ network’, the study recommended mandatory gender diversity awareness training and professional standards training at airlines.

- Airlines and training companies should offer trainer roles on a part-time basis to both men and women.

- To tackle the lack of transparency in the recruitment and selection process, the report recommended that companies approach women directly to encourage them to apply and to look at targeted recruitment campaigns.

- Current female trainers should be made more visible as role models and a formal mentoring scheme should be set up for female pilots and trainers, especially those in the initial phase of their pilot training.

The report also urged the aviation industry to relook at funding structures. Some airlines and training providers are looking at sponsorship schemes and these may go some way in supporting future pilots and diversifying the intake, if diversity and inclusion is to be taken seriously by the airlines.

Skyborne

Skyborne

Achieving diversity

The main objective of the survey is to achieve representative percentages of aircrew at all levels among diverse groups in flight crew by 2035 and to develop a diversity and inclusion (D&I) strategy for the RAeS and the wider airline industry which will provide an effective framework for managing D&I in recruitment, selection and training for the pilot training role. A key focus will be to influence the female pilots who aspire to be pilot trainers, as well as businesses in the industry and the global aviation training market.

What is the future for gender diversity in the pilot trainer role? Myth or reality? – Available to view at the aerosociety.com/media

Pilots from left to right: Iberia, Lufthansa, British Airways and Air France. (Iberia, Lufthansa,BA, Air France).

Pilots from left to right: Iberia, Lufthansa, British Airways and Air France. (Iberia, Lufthansa,BA, Air France). Before women can be flight trainers, they need first to become pilots, a career which involves both emotional and financial investment. Pilot training is expensive: a basic licence costs around £120,000, while further training on passenger aircraft may cost around £30,000.

Before women can be flight trainers, they need first to become pilots, a career which involves both emotional and financial investment. Pilot training is expensive: a basic licence costs around £120,000, while further training on passenger aircraft may cost around £30,000.