DEFENCE E-3D Sentry retrospective

A kind of MAGIC

A ceremony at RAF Waddington on 28 September 2021 closed three decades of Royal Air Force operations with the E-3D Sentry airborne early warning (AEW) platform. Rarely away from the front line, the E-3D and its crews delivered their game-changing capability quietly and efficiently, as PAUL E EDEN explains.

UK MoD/Crown copyright

UK MoD/Crown copyright

Royal Air Force E-3D Sentry ZH103 taxied in at Akrotiri, Cyprus on 31 July 2021, at the end of another mission in support of Operation Shader, the UK’s contribution to the international Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve effort against ISIL insurgency in Iraq and Syria. Formally designated Boeing Sentry AEW. Mk 1, but universally known in service as the E-3D or Sentry, as ‘the AWACS’ in the media and by the call sign MAGIC to its ‘customers’, the E-3D had completed its final operational sortie.

It was entirely fitting that the RAF Sentry should deliver critical front-line capability to the last, upholding a standard its crews had maintained since 1991, when the type flew its first missions. Ironically, this last deployment also saw the E-3D operating alongside the latest expression of British airpower, HMS Queen Elizabeth, its embarked UK/ US F-35B force, and accompanying vessels of the significant Carrier Strike Group 21 under way as the key element of Operation Fortis. The Sentry did what it had always done best, monitoring the airspace around CSG21 as it passed through the Suez Canal from the Mediterranean, into the Red Sea and onward.

Yet the true significance of that final E-3D deployment runs deeper, as Officer Commanding (OC) 8 Squadron, Wing Commander Victoria Williams, explained: “My outstanding E-3D memory is of that final deployment to RAF Akrotiri in support of Op Shader and Op Fortis, and NATO assurance measures missions. We operated across the ‘Med’, Black Sea, Northern Europe and, of course, over Iraq. To have the opportunity to conduct maritime integration training with the Carrier Strike Group on its maiden voyage was fantastic. It was a great opportunity for the Royal Navy to practise tasking the E-3D in preparation for its integration with E-7.”

Williams came to the E-3D in 2013, spending a significant portion of her career involved with it. She continued: “I feel extremely privileged to lead such a historic squadron and such an iconic aircraft out of service.”

All change

In March 2021, Ben Wallace MP, Secretary of State for Defence, delivered the Defence in a Competitive Age paper to Parliament. Among other information under the heading Modernised Forces for a Competitive Age, the document notes: “We will retire the E-3D Sentry in 2021, as part of the transition to the more modern and more capable fleet of three E-7A Wedgetail in 2023. The E7A (sic) will transform our UK airborne early warning and control capability and the UK’s contribution to NATO.”

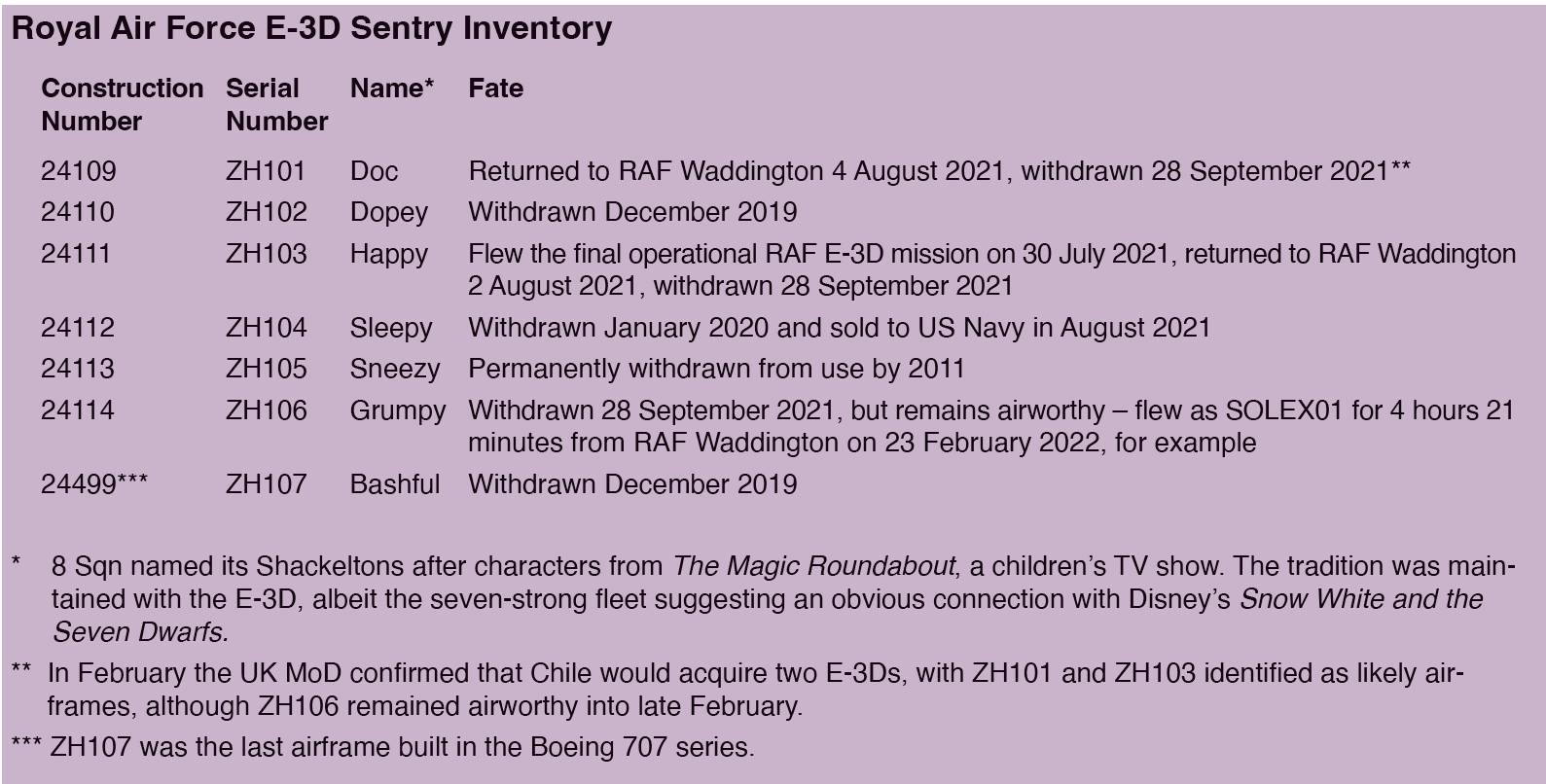

RAF Air Controllers aboard an RAF Boeing E-3D Sentry, conducting a mission in support of NATO. UK MoD/Crown copyright

RAF Air Controllers aboard an RAF Boeing E-3D Sentry, conducting a mission in support of NATO. UK MoD/Crown copyright

The reality of this optimistic statement was a downward adjustment of the government’s intention, announced in October 2018, to purchase five E-7s. At that time, the original seven-strong E-3 fleet had been nominally operating at a strength of six airframes for several years, although serviceability challenges frequently reduced this. Against this backdrop, the exchange of six ageing platforms for five modern, considerably more capable machines seemed reasonable in an era where capability is generally emphasised over fleet size.

Royal Air Force commanders are justifiably proud of their units’ abilities to ‘sweat the asset’, that is, to extract every last drop of capability from every available platform. Time and again, the RAF has succeeded in this way against the odds, achieving results that ought not be possible with limited assets. However, considering the likelihood that one E-7A will generally be in the hangar for maintenance or upgrade, then a three-aircraft Wedgetail force is almost certainly inadequate, regardless of capability.

The UK’s E-7A programme will produce an aircraft formally designated Wedgetail AEW.Mk 1, adopting the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) name for the Boeing 737 AEW&C, through the modification of a used BBJ airframe and two new-build machines. Conversion of the first aircraft is under way with STS Aviation in the UK, with initial operating capability expected in 2024.

Speaking in March 2021, the Secretary of State for Defence was willing to accept a two-year capability gap in UK airborne early warning (AEW) cover. When the Nimrod maritime patrol force was withdrawn in 2010 – coincidentally providing a number of highly skilled operators to the Sentry – Project Seedcorn was established to place RAF personnel within the maritime patrol cohorts of services, including the US Navy and Royal New Zealand Air Force. A similar effort is in place to bridge the AEW gap, a spokesperson for the E-7 Programme Office noting: “The UK has an excellent relationship with the Royal Australian Air Force and will continue to learn from their experience. Importantly, a Seedcorn programme is running with UK personnel embedded with the RAAF on the E-7 Wedgetail. Their experience will form the ‘seeds’ of growth for the future force.”

The Wedgetail will arrive after 8 Squadron moves from Waddington, Lincolnshire, the E-3D’s home station for three decades, back to RAF Lossiemouth, Moray, where it had retired the last of the Sentry’s predecessor aircraft, the Shackleton AEW.Mk 2, in 1991. The Scottish base could be considered the spiritual home of RAF AEW, but also makes considerable sense for the E-7, since it places it alongside the P-8A Poseidon fleet, realising benefits in commonality of service and support, since both are based on the commercial Boeing 737, plus networking of systems and personnel.

Given the small size of the E-7 fleet, pilot training is likely to test airframe availability, but the E-7 Programme Office says: “Personnel will be supported by a range of simulator devices allowing basic conversion training up to high-end warfare replication covering aspects of competency expected from each specialisation.”

From left to right: The E-3D returned to RAF Akrotiri, and Operation Shader, in 2021, having completed its previous deployment in 2016. Here, ZH103 departs for a Shader mission in January 2021; flypast of an 8 Squadron E-3D Sentry during a disbandment parade.

From left to right: The E-3D returned to RAF Akrotiri, and Operation Shader, in 2021, having completed its previous deployment in 2016. Here, ZH103 departs for a Shader mission in January 2021; flypast of an 8 Squadron E-3D Sentry during a disbandment parade.

Sentry drawdown

After persisting with the ambitious Nimrod AEW.Mk 3, an aircraft doomed to failure through insurmountable cooling deficiencies, the UK came late to the Sentry programme, ordering six E-3Ds in December 1986 and taking an option on a seventh the following year. By that time the Sentry was already in Saudi, NATO and US Air Force service, while France ordered the E-3F, sharing the CFM56 engine configuration of the RAF aircraft, in February 1987.

THE E-3D OPERATED CONTINUOUSLY FOR 30 YEARS IN SUPPORT OF NATO AND THE UK. IT WAS INVOLVED IN EVERY UK OPERATION SINCE ITS INCEPTION IN 1991

Wg Cdr Victoria Williams OC 8 Sqn, RAF

The E-3 operators subsequently more or less followed the USAF’s upgrade path for the platform, adopting the Block 40/45 standard of modification as standard during the 2000s. In 2009, the UK elected against Block 40/45, essentially sealing the E-3D’s fate. It would remain highly capable, but inevitably fall behind other E-3s as its modernity plateaued. At the same time, 23 Sqn, one of the two front-line E-3D operators, disbanded, leaving 8 Sqn as the sole operational unit, latterly supported by 54 Sqn (operational conversion unit) and 56 Sqn (essentially developing and honing tactics). Nonetheless, the UK’s 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review foresaw a 2035 out-of-service date (OSD) for the Sentry.

Soon after, fate took an unfortunate hand. A 2016 technical inspection carried out under the Ministry of Defence airworthiness management process revealed issues “…relating to the integrity of the electrical wiring and cabin conditioning systems, resulting in a temporary pause in flying activities”. An 8 Sqn spokesperson detailed the problem: “Unfortunately, the nature of the fault meant that all the aircraft had to undergo a significant inspection regime to ensure the issue had not manifested itself on other airframes. As it turned out, it was not apparent on any other aircraft. But because of the time taken to complete the inspections, the Sentry did not fly for almost three months.”

“This generated significant challenges for crew currency, although a gradual, considered recovery helped us regenerate crews within a couple of weeks. For the most part, subsequent serviceability was relatively good, given the age of the aircraft. There were challenging periods, but serviceability did not result in the loss of any sorties during the Op Fortis deployment over summer 2021.”

Still, when the E-7 deal was signed in March 2019, it was immediately clear that the E-3D would not achieve its 2035 OSD, but the aircraft’s withdrawal, in 2021, was considerably accelerated. Squadron personnel had long envisaged a gradual transition between the E-3D and its replacement, but that was not to be and OC 8 Sqn has been left with the task of helping reassign a team of extraordinarily and uniquely skilled operators. “Sentry personnel have always experienced a bond unlike any other functional area,” she said. “This is particularly important among the mission crew, who came under tremendous pressure to execute orders from higher command and facilitate the requirements of individual platforms during high-intensity operations and exercises worldwide. Long-lasting friendships and working relationships have been forged over the 30 years of RAF Sentry, during mutual participation in these exercises/operations, exchange tours and on academic courses.”

During those three decades’ service, the E-3D operated almost everywhere that British forces were engaged, including over the Balkans, for which the aircraft deployed barely 12 months into its service, during Operation Telic over Iraq, Operation Ellamy, the UK’s part in the international campaign against Libya’s Colonel Gaddafi, and most recently Operation Shader in Iraq.

Unique contribution

It is impossible to summarise the E-3D’s quiet, comprehensive and often unrecognised contribution to UK and coalition campaigns, but the 2011 operation over Libya perhaps provided the aircraft’s finest hour. The 8 Sqn spokesperson provided an operational perspective: “Ellamy was an expeditionary air campaign that epitomised the E-3D’s capability. Because of the location of the area of responsibility, no ground facilities were available, which meant command and control had to be provided by airborne assets 24 hours per day. Thanks to its CFM56 engines, the E-3D could lift (take-off) with more fuel than NATO (TF33-engined) E-3As and so the majority of the daytime tasking was allocated to us.”

“Through the E-3’s excellent 360° radar coverage, the recognised air picture could be produced as tanker and fighter assets reached southern Italy or eastern Spain and, due to the excellent connectivity available, controllers could pass messages directly to higher authorities from the fighters operating ‘feet dry’ over Libya in tactical scenarios – this is known as the ‘kill chain’. It allowed either the red cardholder (a senior commander with the power to approve or deny an attack) or other command representatives in the combined air operations centre to build a mental picture of the tactical situation, including rules of engagement or collateral damage estimation concerns. Decisions could then be made in a very fluid and timely manner to prosecute the target or hold fire.”

Another mission ends at Akrotiri. The E-3 added a comprehensive mission suite to the 707 airframe, most evident through the fuselage rotodome housing the antenna for the AN/ APY-2 radar. UK MoD/Crown copyright

Another mission ends at Akrotiri. The E-3 added a comprehensive mission suite to the 707 airframe, most evident through the fuselage rotodome housing the antenna for the AN/ APY-2 radar. UK MoD/Crown copyright

“Using voice and internet chat-based systems via satcom, information flowed from the fighter cockpit to the CAOC and back again very quickly, taking advantage of fleeting opportunities, yet keeping within the constraints of a very limited understanding of friendly/supported forces’ positions.”

The E-3D flew a complex, easily misunderstood mission set often, far removed from the classic defensive AEW role for which it was commissioned and which had all but disappeared by the time it entered service. Wing Commander Williams summarised the type’s career from a user perspective. “The E-3D operated continuously for 30 years in support of NATO and the UK. It was involved in every UK operation since its inception in 1991 and deployed within a year of entering service. It has operated all over the globe but also remained an integral part of UK homeland defence.”

“Because the aircraft sat away from the action, it is not always apparent to the general public what its impact on an operation was. The E-3D was always there, always watching, providing everyone from pilots in the cockpit, or troops on the ground to commanders in the HQ the whole battlefield picture, in real time, with the ability to talk to everyone concurrently. There will be many fast jet crew out there who have felt the huge relief of having a MAGIC call sign speak to them on the radio and guide them to safety.”

UK MoD/Crown copyright

UK MoD/Crown copyright