AIR TRANSPORT Optimised operational efficiencies

Fly smarter, fly greener

DAVID LEARMOUNT looks at ways in which ‘greener flying’ with highly fuel-efficient flight profiles and optimised trajectories, is now set to be incorporated into airline operations and even pilot training.

Still seen as the environmental bad boy of the global transportation business – whether justifiably or not – commercial air transport is under more pressure than ever before to reduce its global warming impact. Air travel’s environmentally-unfriendly reputation might haunt post-pandemic business, because passengers have had their air travel habits forcibly interrupted for an extended period, and there is no guarantee they will return to prepandemic travel behaviour when the Covid-19 risk recedes.

The industry cannot protect its image solely with promises of future clean power units or developing and producing sustainable fuel products because the benefits of these are not realisable in the medium term, except perhaps at the level of general and business aviation.

Trailblazing UAM

The first commercial aviation sector to go fully electric is likely to be the new urban air mobility (UAM) business, starting out as a provider of air taxi services in metropolitan areas and urban peripheries where battery range limitations are not a problem.

The trouble with claiming this electricallypowered service as an aviation industry eco-success is that electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) vehicles promise – mostly – to replace a small number of existing helicopter operations which have been confined to a niche marketplace by their noise and vulnerability to power failure. The eVTOL operators may also hope to lay claim to a reduction in surface transport congestion and pollution but sceptics will argue that such air taxi services will aid only the wealthy few, at least in their early days. If the more optimistic claims predicting urban eVTOLs’ wide popular usage are realised in reality, UAM will be an entirely new business, not a replacement.

So what improvement opportunities remain for the airlines today? Ask most airline chief pilots whether they work hard today to keep fuel burn to a minimum and they will tell you, in a tone indicating the question is something of an insult, that they have been doing that for decades, which they have.

However, the question remains, could they do more?

Some organisations are looking forensically at operations with a view to improving their efficiency which, if achieved, could leave a beneficial legacy even after the arrival of clean power technology across the industry. Two examples of this are UK air navigation service provider (ANSP) NATS, which is planning to redesign and improve the efficient use of airspace, and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency’s (EASA) Aircrew Training Policy Group (ATPG), which proposes that pilots should be introduced – from the start of their training – to eco-flying techniques, so as to embed a knowledge-based culture of efficient flying.

Efficiency savings

Thus far, the ATPG idea – when presented to unsuspecting current aircrew – tends to elicit the same response as that of the chief pilot described above. However, if you talk to the head of the ATPG, former Ryanair head of training Captain Andy O’Shea, he says it is all about creating a mindset that results in the effortless, almost instinctive pursuit of efficiency, wherever it is to be found but not at the expense of safety. To make efficiency decisions, the argument goes, it is necessary to know what all the potential tools and techniques are. If pilots’ main source of expertise in this area is on-the-job learning from commanders whose only source was the same, chances are that they could miss a trick or two and not even know they had missed them.

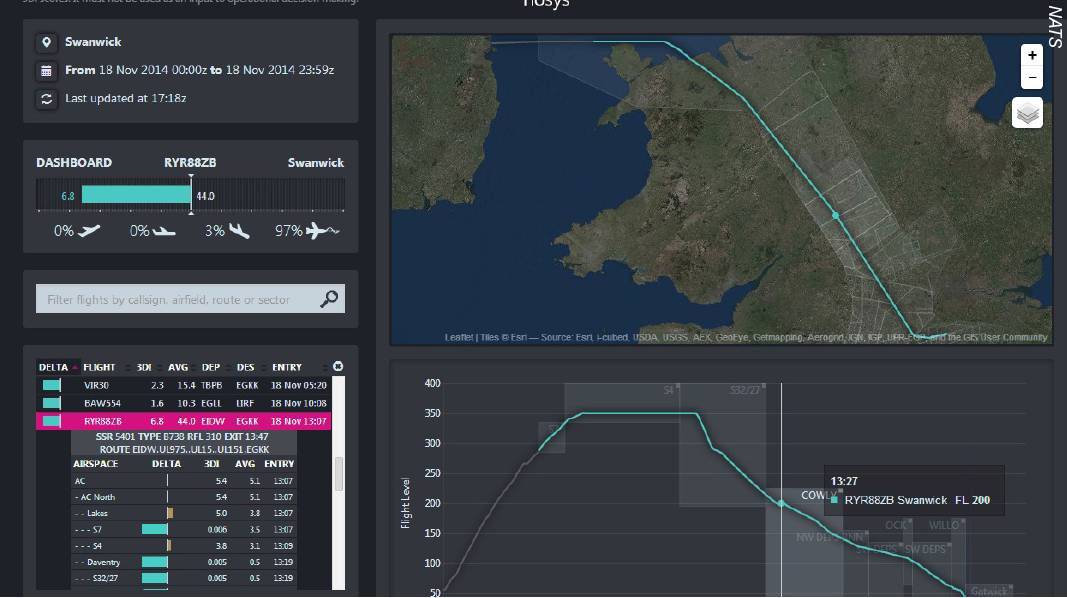

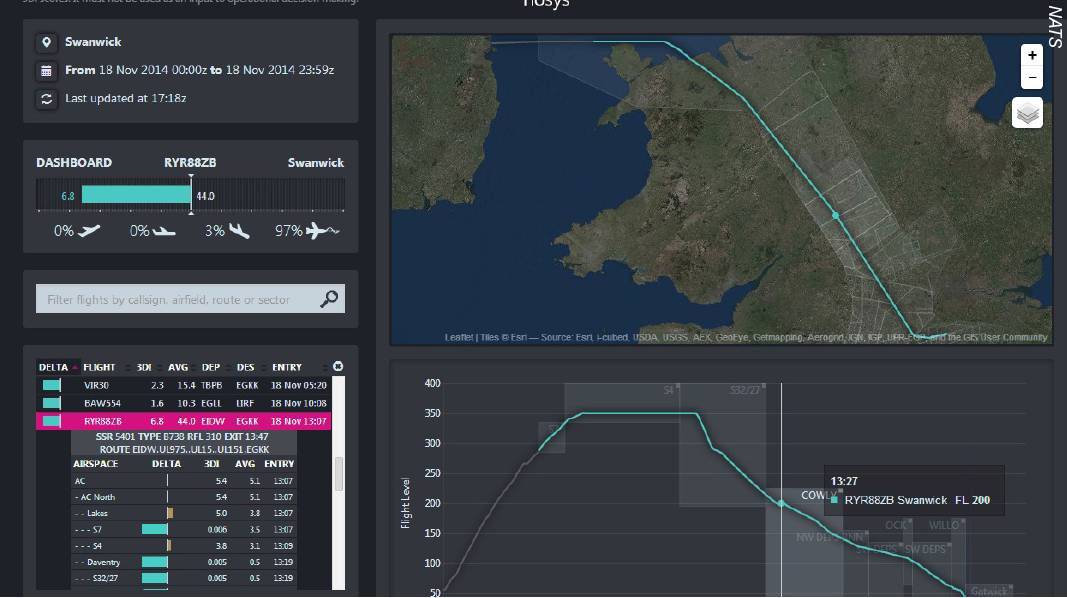

NATS already has a real-time FLOSYS (Flight Optimisation System) to monitor the environmental efficiency of flights. NATS

NATS already has a real-time FLOSYS (Flight Optimisation System) to monitor the environmental efficiency of flights. NATS

NATS’ Head of Sustainable Operations, Ian Jopson, when asked what efficiency advice he would give to aircraft commanders in the commercial air transport industry, replied that they should free themselves (with the co-operation of their operations departments) from an obsession with precise published departure times and manage their departure time so as to achieve the most efficient flight profile that delivers them to their destination precisely at the scheduled arrival time. That sounds so obvious that the average recipient of this advice could, once again, end up feeling insulted.

At present, says Jopson, many flights, using schedules that have not been adjusted for today’s conditions, are arriving early at destinations not ready to receive them efficiently. So, instead of being able to pitch straight into a continuous descent approach to the runway, they end up holding, or having to pursue an extended approach. Sometimes this happens despite air traffic control’s use of arrival phasing systems like AMAN (arrival manager) or EXMAN (extended AMAN).

NATS also uses a system for monitoring real flight profiles and comparing them with ideal trajectories. Called ‘3D Insight’, it enables controllers to review a duty session and compare what they did with what they might have done better. Jopson describes it as a diagnostic tool and explains that it provides scores according to how close to ideal any given flight trajectory was.

Meanwhile, Eurocontrol’s Aviation Intelligence Unit has just published a ‘think paper’, headlined ‘Flying the Perfect Green Flight’. Indeed, Eurocontrol has calculated that, on an average European area flight using current technology, 4,286kg of CO2 2 out of some 16,632kg could be saved per flight just by using what already exists to its best possible advantage. The calculation includes the net benefit of airlines using a fuel mix containing 10% of sustainably generated fuel. The latter, however, is not happening now: the influential IAG Group of airlines promises that it will use 10% of sustainable fuels as standard by 2030. Achieving the ideal flight profile depends not only on the performance of the pilots but of the ANSPs all along the route, and of the airports at both ends. The study provides a useful list of workable actions for airlines to check against their existing practices.

Additionally, Aerion’s recently-cleared spacebased global ADS-B surveillance system has now been integrated with Eurocontrol’s Network Manager Enhanced Traffic Flow Management System (ETFMS), enabling the performance of traffic approaching the European FIRs from any direction to be optimised for entry into the area. Eurocontrol’s Director General Eamonn Brennan says this has the potential to boost air traffic predictability and help with punctuality, improving arrival efficiency and thus reducing emissions.

Trajectory efficiency

NATS, meanwhile, has been taking advantage of pandemic-induced significant traffic reductions, working with commercial airline traffic over the North Atlantic (NAT), to test the feasibility of trajectory efficiency improvement measures. Pre-pandemic traffic levels would not have permitted trials such as this. NATS’ Prestwick-based Scottish Centre, home to the Shanwick Oceanic Area Control Centre (OACC), in partnership with the Gander OACC in Canada, oversees the world’s busiest oceanic airspace. Traffic there is usually managed using the Organised Track System (OTS) but, in early March this year, NATS started using what it calls its ‘OTS Nil’ initiative. Basically, it abandoned use of the OTS in favour of allowing the aircraft commanders to choose their best routing and flight level across the Shanwick oceanic flight information region (FIR), and then to facilitate it.

Overseeing this trial is Jacob Young, NATS’ Manager Operational Performance and Oceanic Group Supervisor. He explained that OTS Nil operations had been ready for use on 1 March but actually were used for the first time on 9 March and, by mid-April, there had been ‘nine or ten days’ on which the Shanwick OACC did not offer an OTS Nil service.

ALTHOUGH PILOTS MAY BE INSTRUCTED IN FUEL-SAVING TECHNIQUES ON COMMAND COURSES, THAT IS NOT THE SAME AS ‘EMBEDDING’ ECOLOGICALLY- FRIENDLY FLIGHT OPERATIONS IN YOUNG PILOTS’ DNA FROM THEIR EARLY TRAINING

This is all very new, Young admits, and the trial is intended to find out if its implementation brings sufficient benefits – without any downsides – to make OTS Nil worth deploying in the long term. He says that, so far, there have been absolutely no snags, aircraft crews had no problem operating the new system, and there was only a very small workload increase for the Shanwick controllers, mainly resulting from simple lack of familiarity. Surveillance can be purely procedural, he explains but, since early 2019 Shanwick and Gander have been benefitting from satellite-relayed aircraft position reports with an approximately eight-second update rate. These position reports are sent automatically via aircraft-mounted automatic dependent surveillance – broadcast (ADS-B) signals which provide the controllers with a radar-like display of aircraft position and data. The crews still report – using HF radio – crossing every 10º latitude.

The OTS system that transatlantic fliers have used for years is basically a set of eastbound routes calculated twice daily to take best advantage of the high-level jet stream and a corresponding set of westbound routes positioned to avoid the jet stream to minimise headwinds. These routes are calculated according to upper wind forecasts and the met information they were based on is 14hr old by the time aircraft use the tracks. If crews can plot their own courses and flight level, they can take advantage of real-time weather information, potentially saving fuel and time. So far, although NATS is gathering comparative data, it does not have sufficient quantities yet results.

Young says that NATS itself does not make any gains through OTS Nil, so it is entirely up to the airlines if they want to take advantage of the greater flexibility the new system provides. Crew feedback has been ‘very positive’ so far, he says, but if airlines want to use it as standard in the future, they will have to work closely with the ANSP, and with the International Civil Aviation Organization, about how best to do it. For example, says Young, the initial flight level allocation scheme would need reorganisation, and at present Gander and other neighbouring oceanic ANSPs are not offering OTS Nil. However, Young is confident, commenting: “We will make this happen in the future if airlines want it”.

Pilot preparation

The world’s busiest oceanic airspace used to be managed using the Organised Track System (OTS) before switching to the ‘OTS Nil’ initiative. NATS

The world’s busiest oceanic airspace used to be managed using the Organised Track System (OTS) before switching to the ‘OTS Nil’ initiative. NATS

On pilot eco-training, EASA’s ATPG has produced an advisory paper that takes – as its starting point – the fact that there is no mention anywhere in training syllabi of preparing pilots to operate in an environmentally-friendly manner. Entitled Environmental Awareness Training for Pilots, the paper points out how incongruous this looks when trade bodies like the International Air Transport Association have, for several years, publicly acknowledged that the industry must strive toward environmental sustainability in the face of accelerating public concern about global warming.

The chief authors of the report – Marina Efthymiou, Assistant Professor in Aviation Management at Dublin City University, and ATPG chairman Captain Andy O’Shea – point out that, although pilots may be instructed in fuel-saving techniques on command courses, that is not the same as ‘embedding ecologically-friendly flight operations in young pilots’ DNA from their early training.’ Efthymiou and O’Shea argue that, if EASA was to accept the paper’s argument and develop appropriate changes, standardising this approach to pilot training – and ATCO training also – it would have the potential to influence a way of thinking, and thus to benefit operational behaviour. Efthymiou adds that fuel management training at airline level is not standardised, neither are its results measured. “The purpose here,” she explains, “is sustainability, not saving fuel costs.’ The group points out that the new generation of pilot trainees are certain to be more accepting of an increased emphasis on sustainable flying than previous generations.

The advisory paper comments: ‘Traditionally the management of these three decision-based functions (fuel, time, noise) has mostly been considered as solely within the remit of the pilotin-command.’ Now, says the study, the proposed incorporation of environmental awareness into all pilot training is intended to ‘encourage good behaviour through early, attitude-forming education, thereby contributing to the improved environmentally aware performance of all pilots.’

The ultimate in green flying training? In February 2021 Green Aerolease placed an order for 50 all-electric Pipistrel Velis Electros with the aim of leasing them to pilot training schools. The Danish Air Force is also to trial the Electro as a zero emission primary trainer. Pipistrel

The ultimate in green flying training? In February 2021 Green Aerolease placed an order for 50 all-electric Pipistrel Velis Electros with the aim of leasing them to pilot training schools. The Danish Air Force is also to trial the Electro as a zero emission primary trainer. Pipistrel

Rebalancing training

ATPG leader Andy O’Shea believes that adopting this proposal need only entail a ‘rebalancing’ of existing training programmes, not radical change, embedding objectives in already-adopted safety instruction concepts like threat and error management (TEM) and competency frameworks. He suggests that ‘by recording objective observable behaviour (OB) and TEM outcome data on how recurrent pilots manage environmental scenarios, powerful insights can be generated to help drive a feedback loop into initial type rating training.’

At the same time, the group is working with the Netherlands Aerospace Centre (NLR) on a start-up zero-emission PPL school and working out how its environmental paper and ‘test-driven development’ concept for rule making and programme design could help them to build an innovative, efficient and quality training programme using electric aircraft.

In its conclusions, the ATPG study calls upon EASA to ‘launch a rule-making task to modify or create a new implementing rule or acceptable means of compliance to achieve these goals.’

Meanwhile, at a time when airlines are spending some of their public relations budget on campaigns to persuade travellers how ecologically aware they are and are offering opportunities for passengers to purchase carbon offsets for their travel, appearances as well as substance matter. Passenger environmental sensitivity is of particular concern in a post-pandemic world, because passengers’ flying habits have been severely disrupted for an extended period and there is a risk that they may have been changed for good. At the same time, movements like ‘Flygskam’ (Flight Shaming) are competing for passengers’ attention. Thus, being able to claim – truthfully – that ‘this airline’s pilots are trained to care about our skies’ just might prove a brand – or even an industry – marketing advantage.

Cutting Aviation’s Climate Change Impact, RAeS Conference 19-20 October 2021, RAeS HQ/Virtual, London