AIR TRANSPORT Airbus A321XLR development

Extra long-range, extra near future

Already a single-aisle sales success, the Airbus A321 is set to power further ahead with the longer-range XLR version, now under development. JOHN WALTON reports.

Airbus

Airbus

In its three decades of service, Airbus’ A321 has evolved from a niche higher-density short-haul hopper to its latest form: the A321XLR version of the A321neo, the largest, longest-range and most capable version of Airbus’ most successful aircraft family.

At present, more than 420 A321XLR – that’s for ‘extra long-range’ —are on the order books. That is roughly as many A350s as Airbus has built and that number is due to rise, especially as airlines seek flexibility in their fleeting and operations in the Covid-19 context.

AEROSPACE sat down with Antonio Da Costa, Airbus’ Head of Single-Aisle Marketing, for the latest on the aircraft’s prospects. “First and foremost,” Da Costa begins as he sets the scene, “the A321 XLR is a fully-fledged member of the A321 family, which is itself a fully-fledged member of the A320 family.”

At its most basic level, he explains, the A321XLR is “no more than taking a regular A321neo and doing some small but significant modifications to it.” The principal changes are the rear centre fuel tank, located just aft of the wing centre box, and increasing the maximum take-off weight.

“Putting all of this together,” Da Costa explains, “gives you the capability for the A321XLR to fly up to 4,700nm, which is roughly speaking ten hours.” That would be roughly the equivalent distance of Beijing to London, Perth, Addis Ababa or Vancouver.

A late-model standard A321ceo, the current engine option version with range-increasing sharklet winglets, can fly 3,200nm (roughly London to Dubai), while some earlier models maxed out at around 2,300nm (London to Baku).

It is a big range boost for an aircraft that was, prior to the neo generation, and even more so prior to the sharklet era that started in 2012, a higher density, shorter-range workhorse. Introduced in 1994, some six years after the original A320, the A321 allowed airlines already operating the smaller A320 to flexibly size up to the larger A321.

The A321neo’s immediate predecessor, the A321ceo, enjoyed moderate success, particularly in its later years as range —and airline passenger capacity demand – increased, eventually selling 1,791 models compared with 4,770 of the smaller A320ceo and 1,486 of the shortened A319ceo.

For the neo generation, however, the larger A321neo models are substantially more popular, with 3,448 orders compared with 3,852 for the A320neo (and just 72 for the A319neo). Indeed, given a number of factors, it would not be surprising if, at the end of the A320neo family’s production run, the A321neo outsold its smaller sibling.

More than 500 A321neos have already been delivered and its latest version, the A321XLR, is being built right now. “We’ve had the first components, especially on the rear central tank, manufactured and delivered to us in the summer of 2020,” Da Costa says. “We’re now proceeding with the assembly of the major components. In terms of the overall milestones, we will then be producing the aircraft, testing it and delivering it – for delivery in 2023.”

As for the A321XLR sub-variant of the neo, “order book wise,” explains Da Costa, “it’s part of the A320 family first and foremost, of which we have 5,700 orders still on backlog out of nearly 15,500 orders in total. And, of these, we have over 420 orders for the XLR with over 20 customers.”

Upsizing your order

However, there is another factor at play too and it may mean that the order numbers for the A321neo –and indeed the A321XLR – may be soft compared with what is eventually delivered. It revolves around the way that airline orders are bought, paid and accounted for, and the marginal cost (or lack thereof) of producing aircraft.

Airbus

Airbus

To perhaps oversimplify, if Ruritanian Airways puts in a firm order for 50 A320neos, it pays a lower price for the smaller and cheaper aircraft than it would for 50 A321neos, both on signing and on delivery. Cost structures are more complicated than that, so this is something of a simplification.

While Airbus no longer publishes list prices, its last list in 2018 had the A320neo at $110.6m and the A321neo at $129.5m, so the difference is not insignificant even before getting into the more complex and more expensive A321LR and A321XLR family members.

Airbus, for its part, has a certain number of slots for A320 family aircraft on its production lines, whether that is an A319neo or an A321XLR, so the marginal cost to the manufacturer of producing a larger aircraft is, materially, in the cost of components. Airbus is thus happy to have airlines upgrading to larger aircraft, even until relatively late on in the process.

So, if Ruritanian Airways(or indeed Ruritania Air Leasing) wants to minimise its outlay on signing, it might order 50 A320neos but later decide to take 25 of those as A321XLRs, and only have to pay the difference at a later date.

“Some customers have indeed engaged with new orders; some are upsells from existing orders,” Da Costa confirms. “Some people are interested in converting some of their orders from whatever aircraft type they had to an XLR and that’s the beauty of having a family of aircraft: we can offer that possibility to our customers.”

Yet, even before Covid-19 threw airline planning and strategy into disarray, “the true value it brings is that we understand that our customers’ environment changes,” Da Costa says of the flexibility between models. “These orders that they’re putting in are sometimes for over 100 aircraft, with a delivery flow that spans several years. You can’t expect the environment to be the same ten years from now as what it is today. Therefore, it is important for us to offer that flexibility to our customers: that they are allowed to change their mind, and we can find solutions that are suited for a changing business environment.”

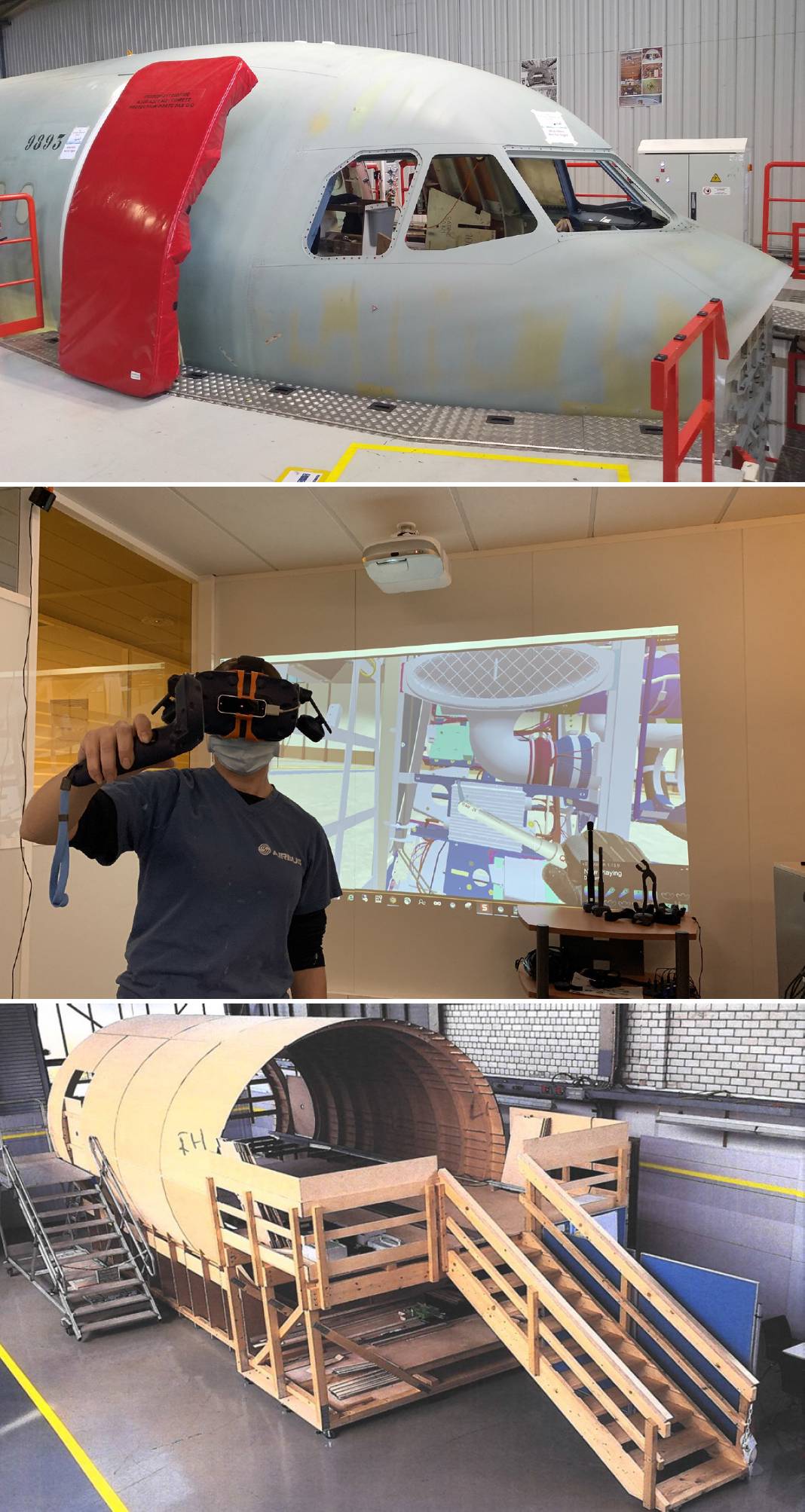

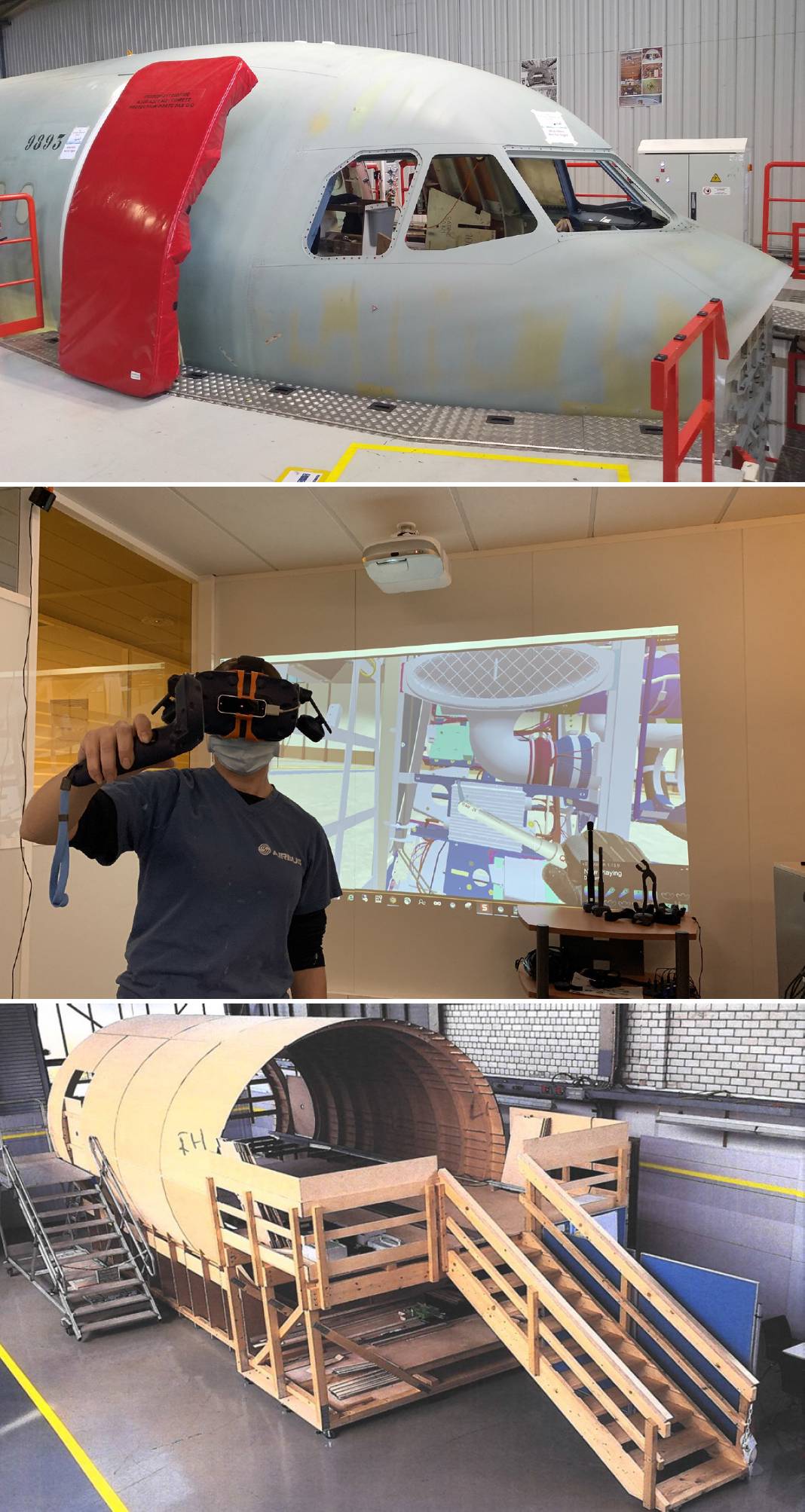

A321XLR Physical Mock Up (PMU) for the Nose and Forward Fuselage (NFF) in St Nazaire. It is based on a standard A321 fuselage from the production line. Airbus

A321XLR Physical Mock Up (PMU) for the Nose and Forward Fuselage (NFF) in St Nazaire. It is based on a standard A321 fuselage from the production line. Airbus

As the 757 flew off into the sunset, airlines wanted their MoM

Until the Covid-19 crisis, the hot topic in aviation was the set of missions known as the middle of the market or ‘MoM’: the edge cases between medium and long-haul, which do not quite need the capacity and range of a 787 or A330, but could not quite be served by a standard A321neo or 737 MAX.

These had previously been served with the Boeing 757-200. However, with the 757 line dismantled as the 787 was produced, the remaining suitable airframes ageing substantially —and no 757 replacement produced by Boeing despite a number of concepts and proposals – the gap in the market became more pronounced.

In the long-haul world, Da Costa summarises: “there are routes which are not quite suited for widebodies, because simply there’s not enough passenger demand to fill a widebody. The next largest aircraft in the portfolio today is the A321. Hence the question of ‘what can we do with this size to go further?’”

The answer to that question? “The A321LR, which was already giving the transatlantic capability to the A321 to go 4,000 nautical miles,” Da Costa says. “This only further excited the interest of our customers, saying ‘this is great, and we would certainly like to go even further on the transatlantic routes, or even further across Asia, or from Europe into Asia.’”

From the outside, it is hard to distinguish any changes from the A321neo in the high-commonality A321XLR variant. The 12,900l rear centre tank, electronic rudder system, optimised trailing edge flap, centre wing box, new fuel lines and hydraulics, larger wastewater tank, single-slotted inboard flap and upgraded maximum take-off weight (MTOW) landing gear are either entirely internal or by no means the kind of visible generational leap like the sharklets or indeed the 737 MAX’s split winglets.

“The majority of the aircraft is exactly the same as the stock neo,” Da Costa says, “which is great because it gives that flexibility to customers: if they want to operate long haul they can; if they want to operate short haul they can as well.”

This high commonality makes it low-risk for manufacturing, particularly compared with, say, a further stretch to the aircraft (though an A322neo would not be beyond the realms of possibility) or a new composite wing.

Low-risk manufacturing has been a point of principle for the programme. Even the most visible cabin enabler for the XLR, the revised door layout that the airframer calls Airbus Cabin Flex, debuted on an earlier A321neo.

Iterative development

Internally, the larger XL overhead bins from FACC arrived on American Airlines’ first A321neo in 2019, while the remainder of the redesigned Airspace cabin will first fly with JetBlue later this year.

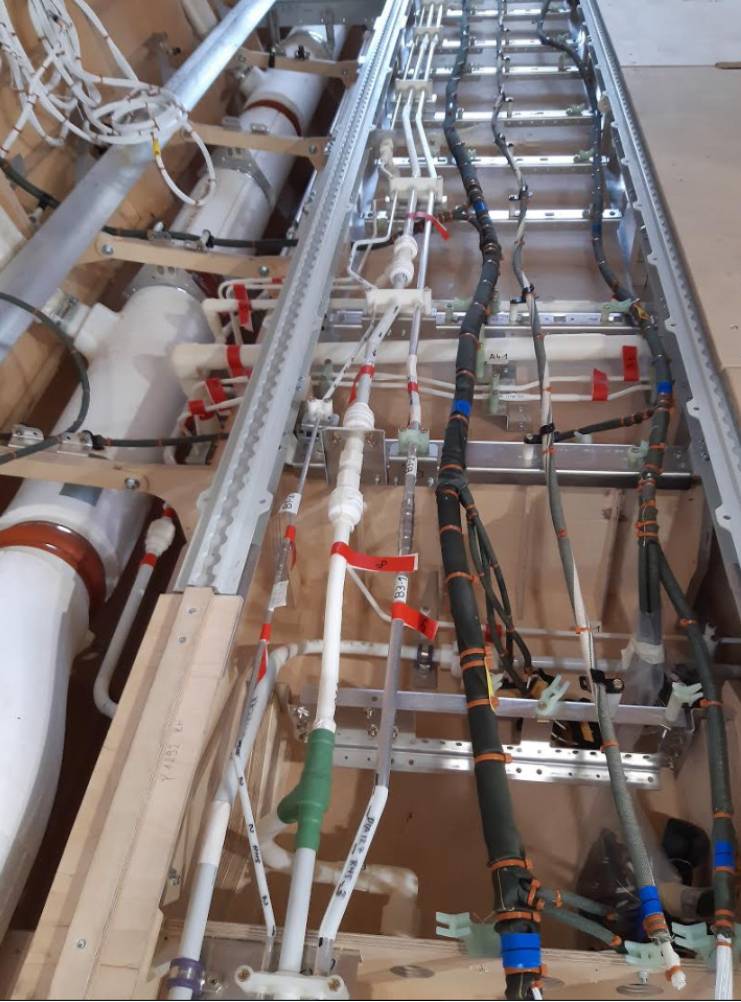

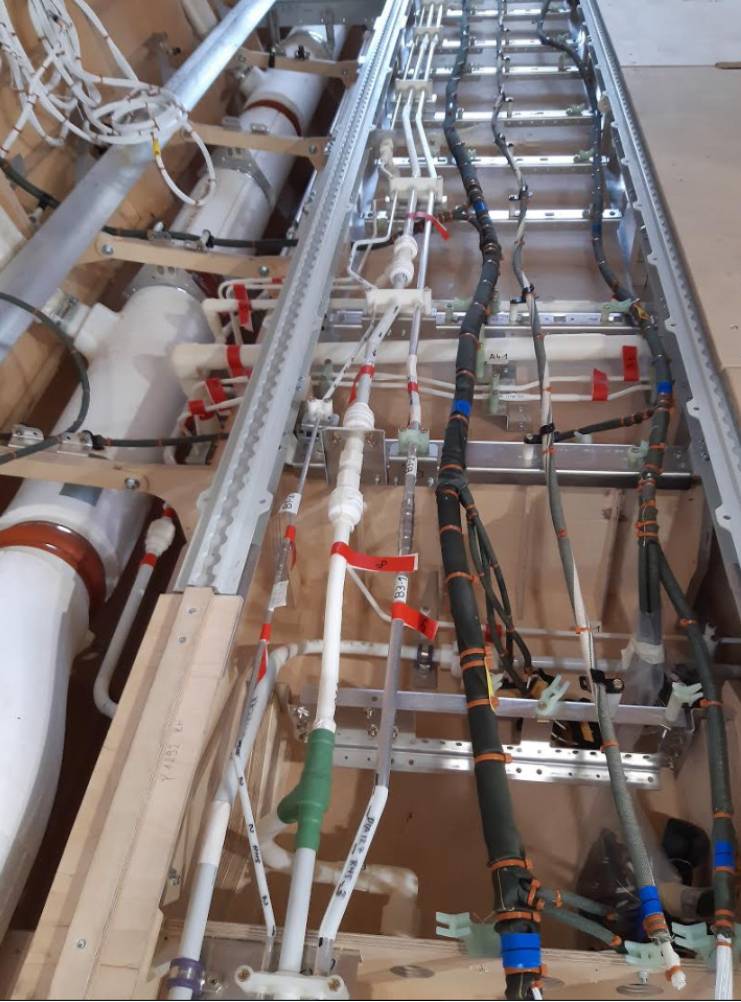

Underfloor cables and pipes in a A321XLR mock-up. Airbus

Underfloor cables and pipes in a A321XLR mock-up. Airbus

It is this sort of ‘little bang’ industrialisation strategy, with its continuous and iterative improvement, that has served Airbus well so far. While there were issues in some areas – wiring issues around the Airbus Cabin Flex door layout in particular – the consequences were problematic rather than catastrophic in terms of production. Assembly line hiccups are difficult enough in the widebody world but, in the high-volume narrowbody arena, keeping hold-ups off the line is critical.

“Our primary assembly line is in Hamburg for the A321XLR: that’s where the first XLRs will be assembled,” Da Costa says. “We’ve even set aside a dedicated hangar to start dealing with what we call the major component assemblies of the XLR separately.”

In essence, these larger component assemblies bring together key parts of the A321XLR that are materially different to your average A321neo before they get to the final line. Rolling them into the final assembly hangar, already sub-assembled, means that the high-volume A320 family line isn’t disrupted in the event that, say, there’s an issue with getting the new fuel tank into place.

“We are dealing with these components’ assemblies in a special way for the first aircraft,” he notes, “but the final assembly line itself will be the same one as any other A321 in Hamburg.”

There are no details yet, however, on the completion side, particularly around the more complex cabins. Installing, say, a dozen business class seats and a dozen premium economy seats, plus in-flight entertainment systems, power (via either or both USB standards, AC outlets, or wireless), and on-board wi-fi, compared with 239 basic slimline seats with neither bells nor whistles, is a complicated endeavour. It is one that has resulted in delays in the past, especially when business class seats miss certification and production deadlines.

Airbus is not exactly lacking in space in Hamburg with the A380 programme ending, so a smart bet might be on taking over some of this space as a postfinal assembly line finishing post for cabin completion, which is the company’s Hamburg specialty.

While all XLR eyes are on Hamburg at present, there are, Da Costa notes, “options of considering final assembly lines elsewhere should there be market demand justifying it.”

Airbus is using new techniques to keep the lines rolling

Airbus is de-risking the A321XLR programme with a variety of demonstrators and pathfinders, both digital and physical. This started with a mixture of 3D digital data, including virtual and augmented reality, to model the aircraft in three dimensions. Physical demonstrators, whether the classical wooden mockup or additive/3D printing parts, also assisted in turning that model into reality.

A blend of physical and virtual mock-ups. Airbus

A blend of physical and virtual mock-ups. Airbus

Most recently, the full-size Pre-Industrial System Accelerators, or PISAs, for the centre and aft fuselage and nose and forward fuselage sections have been installed in Hamburg and Saint Nazaire respectively.

For the forward section PISA, says A321XLR airframe leader Martin Schnoor, “we are focused on the XLR’s structure reinforcement due to the different loads and also on the new systems improvement for cabin comfort. The physical mock-up gives us the opportunity to bring all modifications together from airframe, systems and cabin to confirm the industrial interfaces.”

Hamburg’s centre and aft fuselage mock-up, meanwhile, involved pulling a ‘Standard-008’ (for the A321LR) centre and aft fuselage section off the production line to turn it into the demonstrator for both that LR model and the ‘Standard-009’ (for the A321XLR) example. Below the cabin floor, the demonstrator is being configured in full XLR mode. However, in the cabin the shared Airspace cabin elements means that it can be used for either.

A blend of physical and virtual mock-ups This mock-up is “focusing on the XLR’s major components, including the rear-centre-tank integration, water tank integration, the extended fuel system and the modified hydraulic system,” Schnoor explains. “Here, we take full advantage of the proximity of the rear fuselage physical mock-up to the final assembly line to provide production operator training before they go into the first serial produced aircraft.”

More widely, says Hauke Delmas, Head of SingleAisle XLR, equipping “all these demonstrators help us to observe the systems, activities, workflows and premises under holistic real conditions at an early stage before start of production. The demonstrators, along with classroom training and VR/AR training, will be an integral part of our employee training and onboarding in the future. They provide a protected space for learning and further development. It is thus possible to learn from mistakes on the mock-ups without endangering production or safety.”

“Of course,” Delmas concludes, “it also makes sense from a business point of view to decouple ongoing production from design changes, modifications, new installations and the training of new employees.”

Moreover, Airbus is also using demonstrators for customer support and maintenance, repair and overhaul teams in order to enable them to create the technical and repair documentation that will be used by operators when the aircraft are in service.

Scores on the doors: Airbus’ Cabin Flex options

When the A321neo first flew, it offered four pairs of doors: one at the front of the aircraft, one ahead of the wing, one behind it and one at the rear of the fuselage. In some cases, this led to cabin inefficiencies where emergency exit spacing requirements meant extra-legroom rows were installed or seats immediately next to the door were omitted from the layout.

To solve this problem – and indeed the problem of the 757 where operators were able to choose between multiple door configurations at the time of purchase that did not necessarily reflect the priorities of the aircraft in later use – especially in the context of higher-comfort, lower-density, long-haul cabins where not all the exit capacity would be required, the Airbus Cabin Flex system was devised.

La Compagnie’s A321neo has doors 3 over the wing and doors 4 behind it deactivated. John Walton

La Compagnie’s A321neo has doors 3 over the wing and doors 4 behind it deactivated. John Walton

This replaces doors two ahead of the wing with two smaller overwing exits. Doors three are moved four frames rearwards and a selection of these doors can be deactivated at the time of cabin configuration to allow for cabin optimisation.

“By doing so,” explains Antonio Da Costa, “we are freeing cabin space, which allows customers to either offer a higher level of comfort to their passengers – which is what we expect to see on the XLR being flown long-haul routes with 2, 3 or 4 class layouts – or, for low-cost carriers, allowing to carry more passengers and therefore making those flights even more affordable to passengers.”

Eagle-eyed plane-spotters can determine whether doors are activated or deactivated by looking for a thin band of contrasting colour around an active door. Doors not required to be used as emergency exits remain installed but are physically locked and hidden behind the sidewall so that most passengers would not even notice them and are not outlined in contrasting colours on the outside of the aircraft.

All business class La Compagnie’s 76 seats require just one of the sets of overwing exits active, with the behind-wing doors and the other overwing exits deactivated. At present, the highest capacity A321neo flying is the Wizz Air version at 239 seats, which has all three sets of doors and two sets of overwing exits active.

That is not even the maximum-passenger or ‘max pax’ layout for the aircraft. Cabin Flex allows the A321neo to be certified for up to 244 passengers, with what Da Costa calls “a well-designed cabin layout, in terms of the monuments and the way the seats are placed at 28-inch pitch. Should a customer want to have that, we can offer that solution.”

Let us say that La Compagnie decided that it wanted to add an economy or premium economy section, or its aircraft passed to another operator. The process for door reactivation, Da Costa explains, “is actually very simple” once airworthiness certification with regulators for the new seat layout has been agreed upon.

Once the operator secures that, “should there be a change of the layout from the customer, or the aircraft moving from one customer to another customer,” Da Costa explains, leading to a need to reactivate the doors, “all you need to do is change the sidewall panel.”

Certification on track for 2023

With the 2023 delivery date on the horizon, Airbus explains that it is “working with the certification authorities, including EASA and FAA, just like with previous development programmes. Anything raised along the way will be dealt with to fulfil all requirements for the type certification.”

This, of course, includes the regulators putting the aircraft’s changes out for consultation from interested parties, and indeed Boeing Director for Global Regulatory Strategy, Mildred Troegeler filed two of the three total responses to EASA’s consultation document around the idea of an additional fuel tank.

Boeing, of all companies, commenting on narrowbody safety regulation may raise eyebrows from some – as, indeed, may the fact that the company’s 737 MAX family also intends to offer an additional fuel tank.

“Special conditions and public consultation are a normal part of this process and our work with the authorities will ensure full compliance,” Airbus confirmed to AEROSPACE in a statement. “We will also undertake a flight test campaign with three aircraft. Certification will be fully documented in the normal way.”

Airbus’ delivery dates are likely to come at just the right time, with many in the industry expecting 2023 to be a year of much change and reacceleration for commercial aviation, especially for longer routes.

“This is the lowest-risk aircraft to open long-haul routes,” Da Costa emphasises, highlighting a 30% fuel and emissions reduction compared with “the previous generation of long-haul single-aisles”, and “significantly lower” emissions and fuel burn compared with widebodies.

“In a recovery where long haul has suffered very deeply because of the Covid crisis, starting with a low-capacity low-risk aircraft is the right way to reinject energy into long-haul networks,” Da Costa says.

The crux for Airbus will be managing the return to manufacturing pace for the A320 family line, and to securing production capability.

“Our main priority really is to gradually increase our production rate from 40 a month, where we are right now, towards 45 by the end of this year, and then see how we will move ahead from that into the future,” Da Costa says. “Our big challenge really is on ensuring that we are producing the right number of aircraft to our customers. The XLR fits in perfectly, because this is an aircraft that we see a very strong demand [for] as part of this recovery.”

Airbus

Airbus