SPACEFLIGHT Return to the Moon 50 years on

Walking on the Moon again?

From his vantage point of working on the Apollo Program in the 1960s in Houston, PAT NORRIS FRAeS looks at current attempts to return humans to the surface of the Moon.

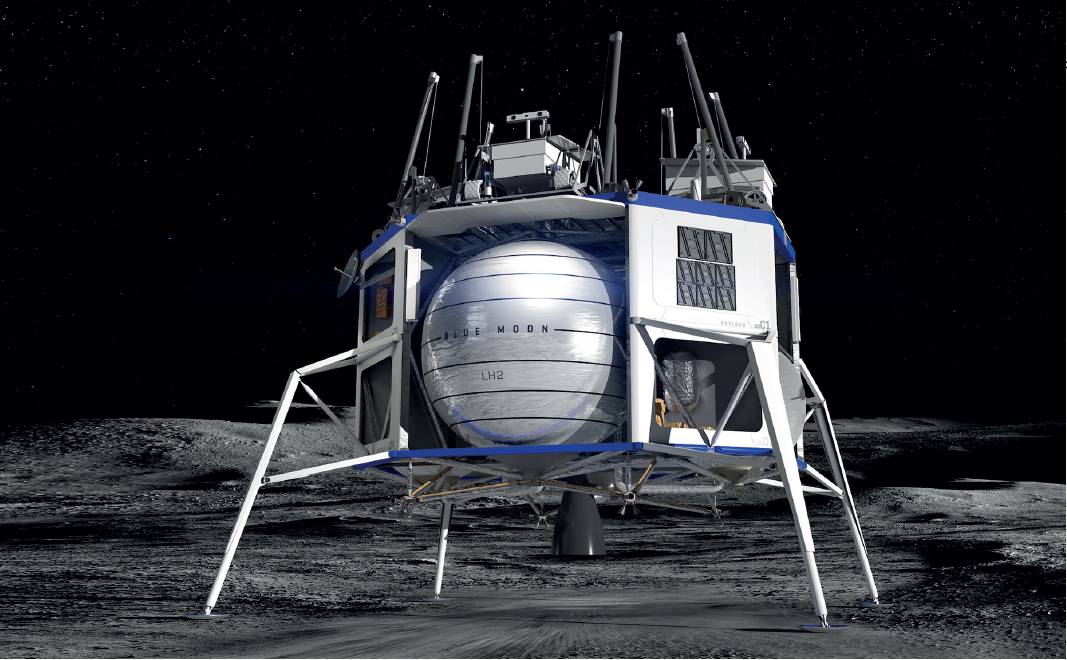

In May of this year, Jeff Bezos, founder of Blue Origin, unveiled this concept for a Lunar lander the company has been working on. NASA

In May of this year, Jeff Bezos, founder of Blue Origin, unveiled this concept for a Lunar lander the company has been working on. NASA

It is hard to get to the Moon, especially if you want to come back! The first humans stepped onto the Moon’s surface 50 years ago this month but no one has been back there since the last Apollo mission in 1972. The details of that first mission, Apollo 11, highlight the technical challenges involved.

The Apollo 11 Lunar Module that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin piloted down to the Sea of Tranquillity on 20 July 1969 weighed just over seven tons. It had weighed 15 tons when it left Michael Collins in the Command & Service Module (CSM) two and a half hours earlier, then burned up 97% of its eight tons of propellant in landing. Of the seven tons that landed, about two and a half tons were left on the surface – the descent engine, used equipment, science instruments, the spindly landing legs, etc. Half of the estimated five tons that took off from the Moon was fuel to get them back to the CSM – you have to reach a speed of about 3,800mph to go into orbit around the Moon, made easier by virtue of the Moon’s gravity being only one-sixth of that of the Earth.

The CSM weighed 17 tons as the three astronauts cast the Lunar Module adrift and fired up its engines to get out of lunar orbit and head for the Earth, in two and a half minutes the engine consumed four and a half tons of propellant. As they approached the Earth they jettisoned the Service Module part of the CSM so that the vehicle that landed on Earth weighed slightly less than five tons.

Pat Norris speaking

at RAeS HQ.

Pat Norris speaking

at RAeS HQ.

The 15-ton Lunar Module and 17-ton CSM that were in lunar orbit started out together as a 46 ton vehicle hurled away from Earth at 23,300mph by the massive Saturn V rocket. That velocity was a lot more than the 17,000mph needed to get the Apollo capsules into a low Earth orbit and required the Saturn V third stage rocket to burn an additional 71 extra tons of propellant. More than 11 of the 46 tons were propellant consumed in getting into orbit around the Moon.