A photo of Yuri Gagarin during training for his first flight backed by stars and galaxies imaged by NASA from the Hubble Space Telescope. Robert Couse-Baker/TASS/NASA

A photo of Yuri Gagarin during training for his first flight backed by stars and galaxies imaged by NASA from the Hubble Space Telescope. Robert Couse-Baker/TASS/NASA

We are 61 years into the human spaceflight era. 61 years since Yuri Gagarin left the known world – indeed ascended beyond the world itself – and looked back on planet Earth.

Hindsight blinds us to the novelty of that moment. We can’t ‘unknow’ what we do now. To find parallels in history, we need to look for moments and people who redefined the maps of their own age and civilizations.

The great ocean explorations of Magellan, Columbus, Cook or Ross widened the chart, while the conceptual transformations of Nicolaus Copernicus and Edwin Hubble changed our own place within it.

The Wright Brothers’ flight at Kitty Hawk (1903) was perhaps another such moment – and we find ourselves as far from Gagarin’s flight as his was from theirs. Gagarin’s personal role was perhaps more symbolic than instrumental – but no less courageous or momentous for that.

The 1960s were a remarkable time. Many of the core features of today’s aviation world were already emerging. The Boeing 747 first flew in 1969. Stealthy supersonic flight had already begun with the Lockheed A-12 (first flight in 1962) and its more famous descendent, the SR-71 (first flight in 1966). The North American X-15 was flying hypersonic and above the von Karman line (100km altitude) in 1963.

Clearly, much has evolved and improved since those days – particularly in avionics – but what really changed, as powered flight reached its hundredth birthday (now almost 20 years ago), was how ‘normal’ it became. In the 1940s, John Gillespie Mcgee Jr in his much-loved poem High Flight, captures the exhilaration of discovering the air:

“Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth of sun-split clouds, — and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of […]"

Today, most of us now take routine flight for granted – but his words have continued to mean a lot to aviators through the years. So much so that Michael Colins took a copy on his Gemini X flight and the poem is reproduced on the memorial for the astronauts of the ill-fated Challenger mission. His words were inspired by propeller flight but seem just as apt for the space era.

“[…] with silent, lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space”

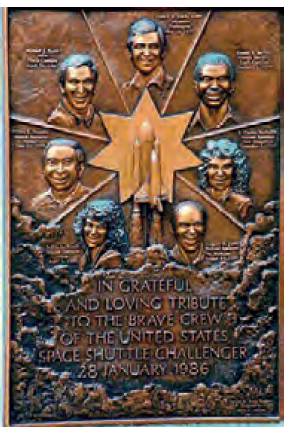

Arlington’s Space Shuttle Challenger Memorial.

Arlington’s Space Shuttle Challenger Memorial.

Since Gagarin’s flight, the Moon landings have provided another clear landmark moment and space stations have sustained presence for longer and longer periods but it seems fair to say that human spaceflight has been expanding the envelope in a relatively incremental way for the last 50 years. Perhaps that is about to change.

Just as the 1960s unleashed aviation, the 2020s are a turning point for space. Ambition is slowly returning to national programmes as political competition reawakens and reviving state interest may yet, itself, be eclipsed by a more agile private sector driven by new-found confidence and a vision of science fiction made real.

In practice, ‘new space’ is a pragmatic world of technology, finance and regulation but that’s a genuine departure from the programmes of the past.

The Moon landings were neither commercial nor scientific. They were politics on a grand scale. The International Space Station has, similarly, been an exercise in gracefully ending the Cold War. So does the lumbering age of geopolitics now give way to the smaller, more agile creatures of the ‘new space’ market economy?

Jeff Bezos, in a recent interview, noted that tourist flights above the von Karman line are a means to ‘practise’. With every flight and system upgrade, experience grows. The operation gets safer; the zero-G gets longer; the possibilities expand and the financing gets easier. Actor William Shatner, made famous as Captain Kirk of Star Trek, made the trip at the age of 90. It is clear that you don’t need to be a steely-eyed, alpha-male fighter ace to visit space. You just need the right ship.

Sub-orbital vehicles, such as those developed by Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic are only a small step from being ‘transport’.

At present, they launch and return to the same site but that is an operational choice, not a technology limitation. Take a different path and these become exotic high-speed transport. Imagine the Friday evening sub-orbital flight from Spaceport America (New Mexico) landing at Honolulu International. A five-hour flight is reduced to a half-hour joyride. It then starts to look like a convenient – if pricey – way to enjoy a luxury weekend break. This globetrotting future is likely to emerge rather slowly though. Airports, regulations, and operational practices all need to fit into the business model, which will take time and a steady supply of affluent customers. What it won not require is a great deal more technology.

It is undoubtedly true that such flights would initially be the reserve of the super-wealthy – but that is much like the early days of air travel - and ocean liners before that. Think of the White Star Line or Concorde in their heyday. Today, the lived experience of air travel is little different to that of a commuter train but the association with aspiration and luxury still clings to the sector. Do you have two hours to kill in Terminal 5? Maybe you should buy a gold watch, some perfume or a fountain pen? We like the thought that air travel is decadent. Sub-orbital transport would reinvigorate that fading cache of travel. New York to Los Angeles or London, San Francisco to Tokyo… “You arrived by supersonic flight? That’s nice. I flew sub-orbital.”.

In January 2022, the US DoD places a $100m contract with SpaceX to demonstrate point-to-point cargo transport for “humanitarian aid and disaster relief”.

Private launch to orbit, with passengers, is now a real thing. For some time, it has been possible to pay for a trip into orbit – but only with the consent of a national space programme. SpaceX and Boeing now both possess the systems necessary to suit you up and put you in low Earth orbit.

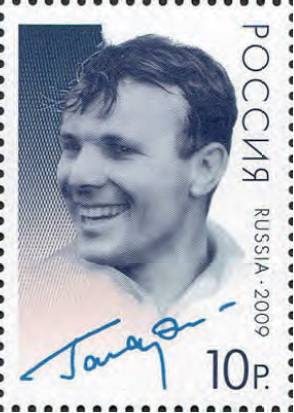

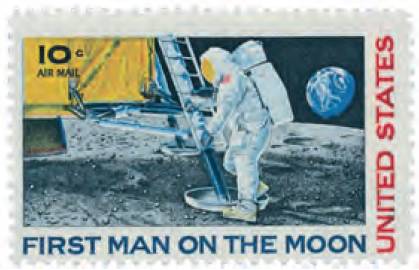

Yuri Gagarin and Neil Armstrong commemorated on their nation’s stamps.

Yuri Gagarin and Neil Armstrong commemorated on their nation’s stamps.

With access to space now in the hands of private enterprise, are the flood gates about to open?

Will holidays on the Moon be happening any time soon?

That, at least, seems unlikely.

A few individuals will have the money and the sense of adventure to try it but a lunar landing is not (yet) a ‘luxury holiday’. These are very personal, risky adrenaline adventures, akin to an Everest expedition or a descent into the ocean abyss. A limited market and one that will wax and wane with fashions for adventure.

Yuri Gagarin and Neil Armstrong commemorated on their nation’s stamps.

Yuri Gagarin and Neil Armstrong commemorated on their nation’s stamps.

Still, hotels – of a sort – do seem credible in low Earth orbit. Imagine taking your good friends for a long weekend in zero-G, floating over the continents and watching the sunrise and fall.

Lightning flashes scatter across the dark clouds below as you clip in for your first night’s sleep, weightless between heaven and Earth.

There are an estimated 56 million millionaires in the world. There is a market.

You may have hired the module for the weekend as a once-in-a-lifetime trip – but if you are seriously wealthy then maybe you got tired of the ocean-going superyacht and traded it in for a whole new type of ship.

With a billion dollars or so splashed on the space-yacht, the few million dollars to get there each time hardly seems to matter. Besides, you can always rent it out to “Big Brother Lifts Off!” when you’re not using it.

Elon Musk notably declared that he would like to “die on Mars, just not on impact”. If he wants to, there appears to be little stopping him. The technology exists to get him there.

Valeri Polyakov spent 437 days in orbit on Mir, between 1994 and 1995. That is substantially longer than needed to get to Mars – albeit without the resupply missions possible in Earth orbit. The Perseverance rover mission has also shown that over a tonne of equipment can be soft-landed on the Martian surface. What makes the trip less appealing is the difficulty in sustaining yourself when you arrive and the difficulty in getting back to Earth in good health (if that was your intent).

It is tempting to view colonisation of Mars as we do Columbus and the Pilgrim Fathers – The first visitors arriving in the New World and establishing a foothold from which to thrive and multiply but it is not like that. In those days of exploration, colonists travelled to create a new life, not unlike that which they left in Europe – farming, building, trading, praying but free from oppression and stifling class structures. They took their way of life with them and started anew. Mars colonists would find a very different world. They would not arrive to uncountable herds of buffalo or virgin forests (nor indigenous peoples, with the skills to get them off the beachheads).

If there ever was life on the Red Planet, then those days are long gone. Humanity will need to work hard for every square metre of Mars that it wants to call home. The most basic resources of human existence – air and water – will need to be managed no less carefully on the surface than they were during the journey through space. Mars is, and will remain, a hostile environment.

Will we see people on Mars within Gagarin’s century? We really might. Will many follow? No.

Jeff Bezos and William Shatner speak after their Blue Origin flight together last year. CNN

Jeff Bezos and William Shatner speak after their Blue Origin flight together last year. CNN

So long as nations compete, the state will retain a major role in space exploration. The space race was not a moment in time. It was a reflection of a basic enduring dynamic: survival of the fittest. If the other team might strive, then I must strive. In their own day, the maritime voyages of HMS Erebus, Endeavour and Beagle were about defending a British position as ‘top dog’. Both the state and private industry will continue to play vital roles in exploration – as they always have.

The International Space Station will be operated until at least 2030. The new chapter in ‘institutional’ space exploration, for the West, is the US-led Artemis program. Artemis now looks set to return humans to the surface of the Moon within the decade. How much further it will go depends a lot on a non-participant: China. From relative ‘space obscurity’, China now has a rover on Mars and a space station of its own. It has landed another rover on the far side of the Moon and returned samples from the surface.

Above left: The Orbital Reef will be a mixed-use privately financed space station in low-Earth orbit for commerce, research, and tourism by the end of this decade. Above right: Inspiration4 was the first private orbital human spaceflight in 2021.

Above left: The Orbital Reef will be a mixed-use privately financed space station in low-Earth orbit for commerce, research, and tourism by the end of this decade. Above right: Inspiration4 was the first private orbital human spaceflight in 2021.

If a new space race has not yet begun, then at least the teams are limbering up – warily eyeing the competition’s every move. China has the skill and the political decisiveness to establish a sustained presence on the Moon. The US does not want to be playing catch-up when potential becomes intent. If a starting gun is fired, the race may be swift. Consider that the time elapsed from Gagarin’s first orbit to Armstrong’s ‘small step’ was just over eight years.

An assertive approach from China will consolidate political will in the West. A lack of Chinese interest will soften resolve.

It is not just about prestigious ‘firsts’ either. When it comes to resource security, then strategic and commercial interests merge. If asteroids and the Moon become a viable source of rare metals then the game changes: commodity price instability, assurance of national supply and arguments over the legal frameworks for exploitation of off-world resources. It will take decades for the metaphorical dust to settle.

Crystal-ball gazing is always a risky business. Nevertheless, it is not entirely fanciful to suggest that the 2061 centennial celebrations of Gagarin’s flight will be celebrated ‘across the solar system’. Perhaps it will also be marked by a new generation of environmental activists campaigning against – or for – human change on other worlds. What are the lessons to take from colonisation of the past and climate change of the present, when applied to asteroids and Mars?

Whatever the debate looks like in 2061, the 2020s will be seen as a turning point when looking back.