DEFENCE Ukraine/Russia War

Air war Ukraine: the first month

Defying many analysts expectations, after nearly a month, the might of the Russian technical aerospace forces has been unable to destroy the Ukrainian air force. TIM ROBINSON FRAeS offers initial thoughts and analysis on the air power aspect of the conflict in Ukraine.

Ukrainian Su-27 fighter. On 1 March, Colonel Oleksandr Oksanchenko, a senior Su-27 display pilot who appeared at the Royal International Air Tattoo was awarded a ‘Hero of Ukraine’ medal after being shot down, reportedly by a S-400 SAM from outside the country. RIAT

Ukrainian Su-27 fighter. On 1 March, Colonel Oleksandr Oksanchenko, a senior Su-27 display pilot who appeared at the Royal International Air Tattoo was awarded a ‘Hero of Ukraine’ medal after being shot down, reportedly by a S-400 SAM from outside the country. RIAT

As this is written, Ukraine is in the fight of its life (its ‘Battle of Britain’ as one commentator noted) after Russian forces invaded on 24 February. As might be expected, details are sketchy, information is unverified and there is a natural tendency for each side to play up successes and downplay setbacks. Despite the granularity of social media videos and photos, which is now backed by open-source intelligence able to geolocate photos from the tiniest details, the ‘big picture’ is somewhat missing – especially from the Russian side and the actual aims of its campaign.

However, we can put together some initial analysis based on observations so far. Firstly, it seems that the Russian invasion has not gone to plan – with one report suggesting the aim was to capture Kyiv and major cities in 48 hours. Some experts predicted that Russia, with investment in cruise missiles, electric warfare, precision-guided munitions, hypersonics and stealth fighters would start with a Gulf War-style ‘Desert Storm’ overwhelming air campaign to destroy the Ukrainian air force on the ground and hit air defence and command centres, before committing its ground forces. Instead, Moscow’s generals appear to have neglected logistics and attempted to initially perform 2003 Iraqi Freedom-style ‘Thunder Runs’ to seize major objectives, without having first achieving air superiority. This has been a very costly mistake.

The campaign opened with Russian cruise and ballistic missile strikes hitting early warning radars and command centres but surprisingly little involvement from tactical aviation – reportedly due to the extremely short notice given to lower commanders that an actual invasion was happening. The major first sign of the Russian plan unravelling was a daring helicopter-borne assault on Hostomel Airport, outside Kyiv, the home of Antonov Aircraft and the giant An225 transporter. In this attack some 6-7 helicopters were reportedly shot down in an opposed landing, along with two of the latest Ka-52 attack helicopters. The Vozdushno-desantnye voyska Rossii (VDV) Russian Airborne Forces involved in this aerial bridgehead were then repulsed, reportingly causing 18 Il-76s with the main force to abort their flight and turn back to base.

Russian Su-25 ground attack aircraft after being hit by a MANPADS. Note blurred serial numbers and unguided rocket pods. Russian State Media

Russian Su-25 ground attack aircraft after being hit by a MANPADS. Note blurred serial numbers and unguided rocket pods. Russian State MediaDespite its massive superiority in combat aircraft (some 300+ combat aircraft vs Ukraine’s fewer than 100), Russia’s air force has been conspicuously absent in the early days of the air war – a fact noted by several defence experts and analysts. Only recently have larger strike ‘packages’ of 10-20 aircraft been observed – but it is unclear how co-ordinated these are. However, these are now attempting to stand off as much as possible, suggesting that Russian attempts to shut down Ukrainians medium SAMs (surface-to-air missiles) have failed.

This is a far cry from the US/Western air power doctrine, which stress large packages of strike, suppression of enemy air defences (SEAD) and escorts to overwhelm the enemy on Day 1 of any air campaign.

The first days also saw little evidence of Russian UAV activity, despite the army’s extensive use of multiple tactical UAVs to cue in massed artillery strikes in Eastern Ukraine since 2014. Only now have Russian-armed UAVs and loitering munitions been seen.

Another observation is that the SA-21/S400 SAM, the ‘big bad’ of NATO planners and a key selling point of the F-35 (buy stealth if you want to fly in airspace where triple digit SAMs are active) has so far failed to clear the skies of the Ukrainian air force – which has amazingly remained operational for longer than expected. This may be down to simple physics, that a SAM system’s effective range is still dictated by the radar horizon while UkrAF tactics in flying low and keeping in the ground clutter may have also helped.

Videos of Ukrainian fighters have seen much low-level footage, which has potentially helped establish the ‘Ghost of Kyiv’ jet ace legend. Russian SAM operators too, may be reluctant to fire into a zone where the majority of their aircraft are operating and where both sides operate similar types. In Georgia in 2008, for example, some three or four Russian aircraft were downed by their own side. As Peter Hoare from the Royal Aeronautical Society’s Air & Space Power Group observes: “Air defence integration has always been Russia’s Achilles heel. Remember how easy it was for Western forces to penetrate Syrian air defences (guaranteed by Russia) to strike chemical weapons’ facilities.”

Additionally, before the crisis, the Ukrainian AF was observed training in dispersed operations from road bases. This, and the difficulty of shutting down airbases completely (NATO planners in the Cold War expected to have to fly repeated strikes against Warsaw Pact bases in East Germany) have potentially assisted the UkrAF to remain operational against a much larger opponent longer than many analysts expected.

As AEROSPACE goes to press, it has been reported that the Ukrainian air force still has around 56 fighters available and is contesting the skies through a small number (10-20) of sorties a day.

Russian Su-34 strike aircraft in Belarus. The fighter-bomber is the only one with a serious PGM capability. Russian MoD

Russian Su-34 strike aircraft in Belarus. The fighter-bomber is the only one with a serious PGM capability. Russian MoD

There have also been calls for NATO or the UN to establish a no-fly zone (NFZ) to protect civilians on the ground from the worst of the air strikes. This would, however, bring NATO pilots into direct conflict with Russian ones, and potentially escalate this into a far wider war, having crossed President Putin’s ‘red line’ of direct involvement in this conflict. The fear is to enforce any NFZ, NATO combat aircraft would have to inevitably attack Russian long-range S400M sites in Russia or face being shot down from afar.

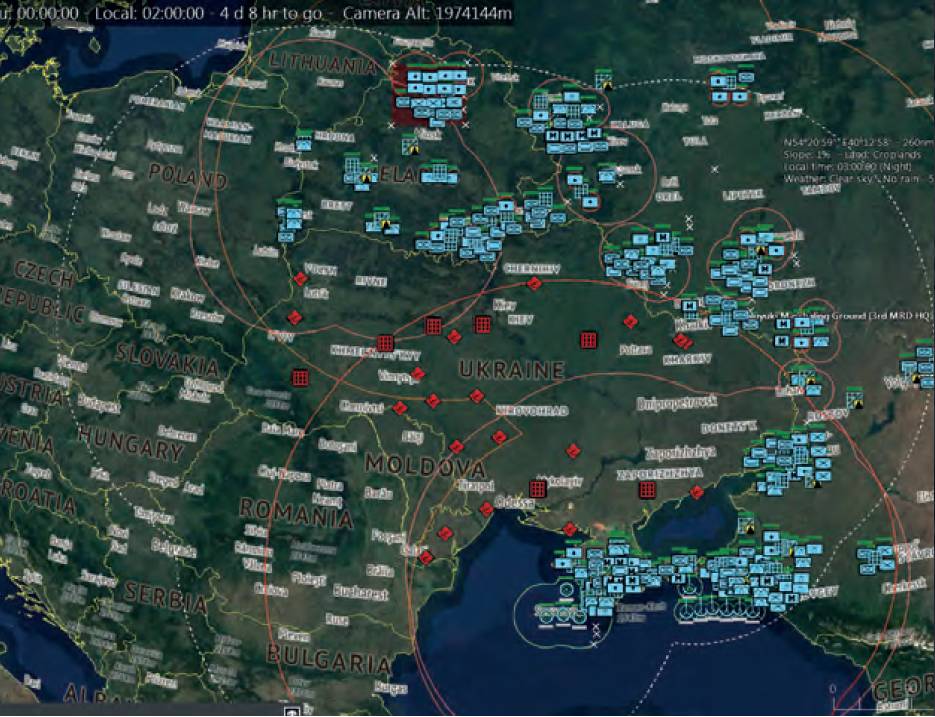

Threat rings of Russian S400 and other SAMs visualised in Command Modern Operations. Command Modern Operations

Threat rings of Russian S400 and other SAMs visualised in Command Modern Operations. Command Modern Operations

However, the President of the UK’s Air & Space Power Association, former senior RAF commander, Air Marshal Greg Bagwell suggested on social media that an NFZ could work – if it was an UN-mandated NFZ, if the risk of escalation was managed (with Western pilots ‘turning the other cheek’ if targeted by SAMs from outside Ukraine) and potentially if F-22/F-35s were used. Using stealth fighters that could ignore S400M’s threat, then engage any airborne aircraft or helicopter (including Ukrainian AF ones) or active air defence units within Ukraine’s own border then, could be a way in which the international community could intervene to protect civilian lives. As Bagwell notes: “would the potential benefits of an International NFZ working outweigh the desire for Ukraine to maintain any indigenous air capability?”

RAeS Air & Space Power Group expert, Peter Hoare, though, warns that despite the Western desire to ‘do something’ and intervene: “Putin’s veiled threat of nuclear escalation makes this [NFZ] a non-starter.”

Meanwhile, on 1 March, UK PM Boris Johnson told the media that an NFZ was “simply not on the agenda of any NATO country” because of the risks of escalation with Russia. “That’s a very, very big step.” NATO leaders and President Biden have echoed this argument.

While an NFZ now seems less likely despite the increase in targeting of civilians, it is reasonable to assume that, having openly supplied weapons and equipment to the Ukraine government, Kyiv is also benefiting from the West’s impressive ISR capability, with satellite, airborne and electric intelligence being passed their way. ISR flights by NATO nations before the conflict while have likely assisted in building up an order of battle and revealing the attackers’ main thrusts.

As AEROSPACE goes to press in mid-March, the Ukrainian MoD claims it has shot down 86 Russian aircraft, 108 helicopters, 11 drones and approximately 20 cruise missiles, with 7,000 Russians killed. Visual confirmation via social media includes three Russian Ka-52 attack helicopters, an An-26 transport aircraft and two Su-34s. A Russian Su-30 fighter was also seen destroyed and on fire at Millerovo Airbase inside Russia that had been hit by Ukrainian Tochka-U ballistic missiles. On 28 February a Russian Mi-35 was seen destroyed in Kherson Oblast – while an artillery strike on a Russian forward operating base at Kherson Airbase destroyed around 16 helicopters. However, while some aircraft may have come down in Russian-held areas, the totals claimed by Ukraine appear to be somewhat exaggerated and it is believed that Russia has lost about 15 fast jets.

Ex-Polish MiG-29s are now in limbo about whether they will be transferred to Ukraine. Polish MoD

Ex-Polish MiG-29s are now in limbo about whether they will be transferred to Ukraine. Polish MoD

Meanwhile, the Russian MoD says it has shot down 11 Ukrainian aircraft, seven helicopters and destroyed 47 aircraft on the ground, while also downing 46 drones. On 1 March the Ukrainian MoD said a high-ranking fighter pilot, Col Oleksandr Oksanchenko (a former display pilot at RIAT) had been shot down and killed flying a Su-27 fighter. Visual confirmation of Ukrainian losses from social media includes An-26 transport, Su-25 ground attack aircraft and a Su-27 fighter, as well as a number of MiG-29s seen destroyed on the ground. However, the snow on these aircraft in the images makes it likely that these were non-operational anyway.

It needs to be remembered however, that these claims from both sides cannot be independently verified. There are also reports that, as well as the ground units experiencing supply and logistics problems, Russia’s air arms may also be running out of their limited stock of precision weapons and countermeasures. Certainly, there does not seem to have been a repeat of the initial cruise and ballistic missile ‘blitz’ where over 300 missiles were launched and Russia now appears to have used around 850 cruise/ballistic missiles, not far off the 1,000 that some analysts assessed were available in total.

On 28 February evidence of unguided air dropped munitions were seen in Kharkiv for the first time – a terrifying prospect for civilians should Moscow decide to raze cities in order to capture them. Peter Hoare explains: “This suggests that aerial bombardment from Su-27s and Su-30s is increasing as heavy ground resistance is being experienced. It is worth remembering that this is very close to the border with Russia so it presents not too much of a challenge for Russian air superiority

Meanwhile, on 16 March, an intelligence update from the UK MoD stated that “given the delays in achieving their objectives and failure to control Ukrainian airspace, Russia has probably expended far more stand-off air-launched weapons than originally planned”, adding “as a result, it is likely Russia is resorting to the use of older, less precise weapons, which are less militarily effective and more likely to result in civilian casualties.” Without NVGs, targeting pods and PGMs – along with RuAF’s lack of training for night operations, this is likely to lead to less effective and more indiscriminate air strikes.

The conflict has also seen geopolitical realities upended overnight, from the assumption that countries with McDonald’s do not go to war, to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline being axed. Germany, in particular, has shifted its stance from its previous pacificist approach to international relations by announcing it would boost its defence spending to 4% to meet and even exceed NATO commitments. Berlin’s decision to acquire F-35 to replace Tornados has been fast-tracked. This is a seismic shift and one where, only a week previously, the German defence industry was on the path to being essentially ostracised from investment markets due to its negative image.

Footage of Ukrainian TB2 drone attacking Russian SA-11 Buk SAM systems on the move. Ukrainian MoD

Footage of Ukrainian TB2 drone attacking Russian SA-11 Buk SAM systems on the move. Ukrainian MoD

Meanwhile, the European Union surprised the world by announcing that it will supply fighter jets to Ukraine via its member states.

This was understood to be either MiG-29s from Poland and Slovakia, as these could be deployed and flown into action by Ukrainian pilots in the quickest time – with the Ukrainian Parliament announcing that it would receive 70 ex-Soviet combat aircraft.

The US State Department also gave its blessing for this idea, only for the Pentagon to reverse its decision after Poland said it was ready to transfer these MiGs to US ownership and deliver them to Ramstein AB in Germany.

It is unknown at this time whether this is because the phase of the conflict is now too late for them to make a difference, and whether this would constitute an escalation in Moscow’s eyes, or whether the upgraded Western MiGs (with, for example, secure NATO radios and IFF) could not be flown by Ukrainian pilots without more training and support than can be undertaken in such a short time.

Meanwhile, Western countries, including nonNATO nations, like Sweden and Finland, are also supplying military aid to Ukraine, including anti-tank launchers and Stinger MANPADS from Germany, Denmark, Poland and the Netherlands.

The conflict is also notable in that, by not framing this as a ‘war’, Moscow has been unable to leverage its slick media and information operations to control the narrative.

In Syria, for example, drone and video cameras, regular war room briefings and embedded Zvezda reporters presented an image of a modern, effective fighting force to the outside world.

In contrast, Ukraine’s determined resistance, charismatic leader and effective messaging has raised morale and also galvanised international support on an unprecedented scale, reversing decades of old assumptions about German and EU political distaste for defence spending, Swiss neutrality and the financial ‘nuclear option’ of blocking SWIFT payments.

Memes and infowar, such as the ‘six-kill’ ‘Ghost of Kyiv’ then, (whatever the reality), have helped internationalise this conflict beyond a local dispute about the Donbass.

It must be borne in mind that this analysis is only an initial one. Events on the ground, and paucity of information mean that it is difficult to assess the situation clearly. However, it does seem that the Russian invasion has not gone to plan and that Moscow’s forces are experiencing high losses in personnel and material – with the Ukrainian air force surviving longer than many analysts expected, given the overwhelming firepower that is arrayed against it. What is true is this conflict has changed everything we know about the post-Cold War world.