GENERAL AVIATION Consumer drone delivery

Drone and deliver

Trial projects are being conducted using drones to deliver fast food and groceries, with plans to expand such aerial services into more widespread use. BILL READ FRAeS examines the pros and cons of using drones for consumer deliveries and asks whether such aerial deliveries are financially viable.

Above left: Manna has begun an autonomous drone delivery service in Galway, Ireland. Above right: Over in Virginia, US, Wing is conducting delivery drone trials. Manna/Wing

Above left: Manna has begun an autonomous drone delivery service in Galway, Ireland. Above right: Over in Virginia, US, Wing is conducting delivery drone trials. Manna/Wing

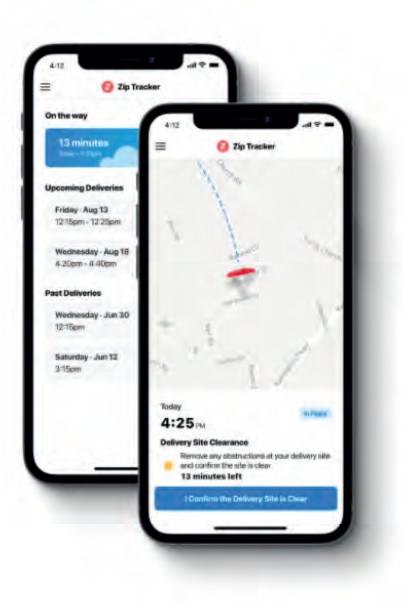

Picture the scene. You are sitting at breakfast and fancy a coffee and a sandwich. No problem – you simply use your smartphone to access your local fast-food supplier and order some. Within a few minutes, a small drone appears and hovers over your garden as it lowers a package containing your purchase onto your driveway. Within ten minutes you are continuing your breakfast.

A vision of the future? Not so – in some places this is already happening and many companies are busy working to introduce this service around the world.

The concept of home deliveries by small cargo-carrying UAVs predates Covid and a number of transport and logistics companies have been working on plans for a number of years, not always successfully. However, as with plans to introduce urban air mobility eVTOLS to carry passengers, there are many challenges yet to be overcome.

Drones are already being used for a wide variety of applications, including monitoring crops and livestock, assisting in search and rescue, inspecting buildings and patrolling vital infrastructure. A particular specialist area is carrying small packages, such as medical supplies, spare parts or military equipment. Deliveries of commercial products direct to customers by drone is also already a reality. A drone delivery company called Wing has conducted trials in the US, delivering consumer goods from local businesses to rural communities in Virginia. Wing also operates a food delivery service from local shops to residents of Canberra in Australia. Over in Ireland, a company called Manna operates an autonomous drone delivery service in Galway, delivering coffee and food products while, in China, transport company JD.com has been operating a rural drone delivery service since 2016.

While small-scale local drone delivery services have so far met with success, attempts to create a wider delivery network have not all been so fortunate. A surprising casualty in the race to implement drone parcel deliveries was global e-commerce mega-corporation Amazon Prime which planned to create a fleet of drones capable of flying up to 15 miles, carrying packages weighing up to 5lb (2.3kg) but abandoned the project in 2021 after failing to fly a single commercial parcel drone. Another company which failed to complete the course was transport logistics company DHL which announced in August 2021 that it would be discontinuing its Parcelcopter delivery drone development programme.

Zipline

Zipline

The creation of a working fleet of commercial parcel-carrying drones for ‘last-mile’ delivery involves a variety of challenges, some technical, some regulatory and some involving non-controllable external factors. The first of these involves navigation. Last-mile delivery drones would have to be able to fly long distances (to reach isolated communities), autonomously, at low levels under 400ft to avoid other airspace users. They, therefore need to be programmed to find their way to and from their destinations without colliding with low-level objects, such as power lines, trees or high-rise buildings, other low-airspace users, such as para-motors, helicopters and military aircraft, ground vehicles and, most importantly of all, people on the ground.

Need a coffee in a hurry? Just order it by Zipline drone

Need a coffee in a hurry? Just order it by Zipline drone

There are currently two main technologies available for drones to detect nearby objects.

The first is radar which sends out radio waves and measures their reflections from obstacles.

The second is lidar, which uses laser beams to provide detailed images of nearby features. Although new technology is improving both systems, they are currently still relatively expensive and heavy which will add to the non-payload weight of a delivery drone.

The drones must also avoid areas with no-fly zones, such as airports, which might lie across their routes.

In addition, the systems also need to be able to identify different objects they might encounter, as well as different types of ground to land on or to place packages – such as the difference between a lawn, a roof and a swimming pool.

In addition, the drone needs to be programmed with algorithms which instruct the systems what to do in an emergency, such as an imminent collision or crash.

In some cases where any action will result in damage or injury, the programmer will need to decide which option to choose.

All these issues needed to be considered over a variety of different scenarios, such as night-time operations, rain, fog, snow or high winds.

Another hurdle is that of regulations. Every country has its own set of regulations governing the use of UAVs.

Many rules for operating personal recreational drones impose restrictions on weight (under 25kg in the US), how high they can fly (not more than 400ft), when they can fly (daylight hours) and where they can fly (must be in the user’s line of sight, must not go near buildings or close to people on the ground).

While many countries allowed exemptions to the standard regulations to permit the testing of long-distance UAVs, many of the rules still do not permit them to be used for autonomous BVLOS flights.

The US, in particular, poses a challenge, in that there are multiple rules to adhere to – from federal agencies, state regulations and city laws.

Above left: DHL’s Parcelcopter delivery drone never got past the proof of concept stage. Above right: Amazon Prime Air delivery drone technology demonstrator. Deutsche Post/Amazon Prime Air

Above left: DHL’s Parcelcopter delivery drone never got past the proof of concept stage. Above right: Amazon Prime Air delivery drone technology demonstrator. Deutsche Post/Amazon Prime Air

In addition to customers planning to use delivery drones as a service, there are also people who are not using them but are living underneath their flight paths whose views will be important to ensuring the public acceptance, or otherwise, of delivery drones. Their opinions will be influenced by two major factors – safety and noise. Delivery drones will have to operate in a thin altitude band, from zero to 500ft, known as very low level (VLL) airspace which will be congested with large numbers of permanent and non-permanent artificial and natural obstacles. Another factor is that delivery drones are expected to be much larger and heavier than recreational UAVs (weighing up to 25kg to enable them to carry large packages) and so could pose a greater risk to both people and property, should they crash due to a malfunction, accident, collision or bad weather.

A major public acceptance issue is that of noise. While the noise of the electric motors in a drone is much quieter than a helicopter, the noise made by a drone’s multiple rotors can be greater, as the smaller propellers have to move air more rapidly to stay aloft. Drones also make higher-pitched buzzing sounds than helicopters, which have much lower frequencies because their larger rotors do not need to rotate as fast to generate the necessary lift.

There are also privacy concerns. In order to navigate to where they are directed to go and to maintain situational awareness, delivery drones would have to have the ability to sense their surroundings, process, transmit and/or record data. This could result in claims of intrusion from third parties, as well as the risk that data gathered by drones related to individuals and property could be misused by third parties.

With growing public awareness and concerns over green issues, a perceived environmental advantage will be an important factor in determining the public acceptance of drones. But how environmentally friendly will a fleet of delivery drones be?

Delivery drones can only deliver over short distances, so more storage and distribution hubs will need to be created from which to operate them, which will increase road traffic. As with other electrically-powered vehicles, there are also hidden environmental costs, such as how the energy to charge the batteries is created and the adverse effects of mining lithium to create the batteries.

There could also be a negative effect on wildlife as birds may view a low-flying drone as a threat or even as prey. There have been multiple recorded incidents in which birds have attacked drones, including one in which Wing had to ground its delivery drones in the Canberra suburb of Harrison after they were attacked by ravens.

In addition to safety, delivery drones could also pose a security risk. UAVs have already been used for illicit purposes, such as smuggling, delivering drugs or weapons and for terrorist attacks. Delivery drone operators would have to set up security systems to protect drones against cyber-attacks which could either cause them to crash or to fly to security-sensitive areas.

Drone deliveries might also trigger a rise in crime as thieves attempt to steal both the drones and their potentially high-value cargoes. There could also be a risk of attacks against drones from individuals reacting against noise, intrusion or environmental concerns or political motivations.

Having looked at the potential pros and cons of drone delivery from a customer and public point of view, it is now time to ask the question – can drone delivery services actually make money? The particular advantage of using drones is that they can fly fast directly to customers and are potentially cheaper to operate than road-based delivery alternatives. Two particular markets have been identified as being ideal for drone deliveries. The first is for local fast food deliveries or small grocery orders – as has already been proved in a number of trial schemes. The second market is for ‘last-mile’ deliveries of consumer goods where it is quicker to use a fleet of UAVs to deliver directly to multiple customers than delivering packages one by one using a road vehicle.

However, although they can fly fast and direct, drones can only deliver over short distances and can generally only carry a single, small, light payload, although some platforms can now conduct multiple drops in one flight.

Above left: The more rotors, the more noisy a delivery drone could be, as seen on this Wing drone. Above right: Drop-off stations do not have to look intrusive – as this stylish Wing drone delivery station at EOC hospital group in Lugano, Switzerland shows. Wing/Matternet

Above left: The more rotors, the more noisy a delivery drone could be, as seen on this Wing drone. Above right: Drop-off stations do not have to look intrusive – as this stylish Wing drone delivery station at EOC hospital group in Lugano, Switzerland shows. Wing/Matternet

The fact that delivery drones today only have a limited range (no more than 15km (10miles) means that they would have to operate from a local hub. If this hub is a local takeaway or grocery store, this would not be a problem but, if the business plan involves last-mile delivery of consumer goods, then each local drone network would need to operate from a local distribution centre. Each of these local warehouses would have to carry a full range of goods which customers might order, as well as facilities for operating drones.

More road vehicles will be needed to take goods to the regional depots which would increase traffic congestion. In addition to the cost of construction, these new distribution centres would require power to operate and staff to work in them which would undermine the cost efficiency of using short-range drones rather than long-distance road vehicles.

Because delivery drones will fly close to people and property, another factor to be considered is that of insurance. Insurance premiums will vary depending on the perceived risk, so drones that operate in populous or high-risk locations will cost more to insure than those in less populated or rural areas.

Another issue is that of delivery points. While having food or groceries delivered by drone may be a viable option for people with large gardens and plenty of open space, it is not feasible for people living in flats or high-rise buildings. The fast delivery option may not always be possible in bad weather or high winds.

Drone deliveries also come with a number of negative elements – most important of which is safety. Suppose the drone or its package lands in a tree, in someone else’s garden, on a roof, a car, a road or even on a passing pedestrian? What happens if the customer who orders a drone delivery has mobility issues and is unable to come out to collect a package? There could be a temptation for antisocial behaviour, such as attempts to shoot down drones carrying high-value equipment or to steal them on the ground. There might even be a risk that the drone navigation systems could be hacked to take them to different destinations. There are also potential issues related to noise, damage to the environment and effects on wildlife.

As with many other drone applications, it could turn out that drone deliveries will operate successfully in specialist niche markets where their twin advantages of speed and point-to-point delivery outweigh the potential disadvantages. In other areas, the issues of safety and noise might turn public opinion against their use. Will the future be being able to order a coffee to be delivered to you in two minutes, or will it be enduring the constant noise of hundreds of large noisy drones buzzing over your head delivering to other people?