AEROSPACE Human factors in air traffic management

The safety factor

RHIAN WILLIAMS-SKINGLEY, Dr ANNE ISAAC and CHRISTINE DEAMER from NATS and the Royal Aeronautical Society’s Human Factors ATM subgroup look at Day-2-Day safety surveys.

NATS

NATS

Aviation is considered an ‘ultra-safe’ system with very small numbers of serious incidents and accidents. However, even in ultra-safe industries, accidents happen that surprise us, where nobody saw the accidents coming. Often in these cases, performance of the individuals, teams and organisation itself ‘drift into failure’. Small changes occur over time that are hard to notice because they gradually become normal. Alternatively, performance can simply become more variable, with no specific trend.

Most safety-critical organisations have systems for event reporting, incident investigation and lesson learning. However, even mature systems related to these functions have three problems. Firstly, the data is reactive rather than proactive; the event has already happened. Secondly, accidents and incidents are often unique events with different patterns of contributing factors. Therefore, preventing future incidents is rarely possible. Lastly, since there are few accidents and serious incidents, we should not rely exclusively on such data for safety monitoring and improvement.

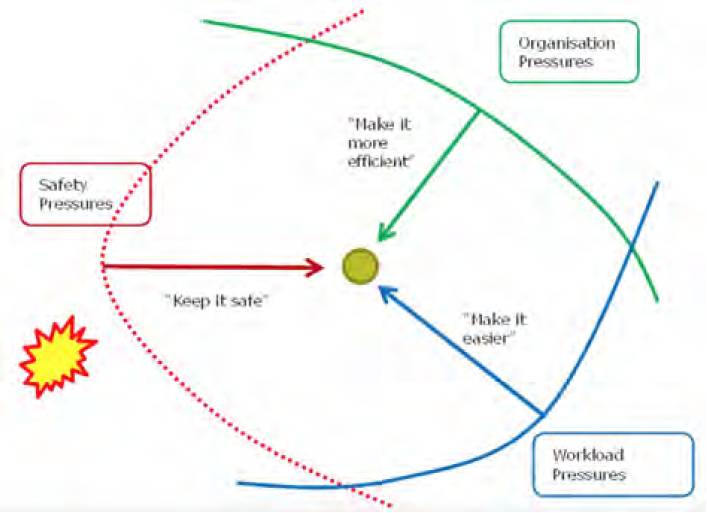

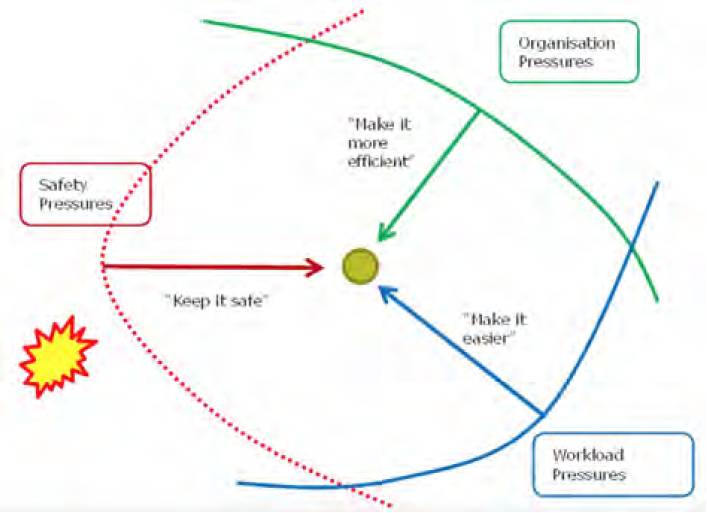

Safety experts also agree that traditional approaches to improving safety are coming up against the laws of diminishing returns and are looking towards other leading safety indicators to help them understand safety and human performance. Figure 1 shows the different pressures which all operations are continuously under.

Increased safety efficiency

Organisations place pressure on the operation to ‘make it more efficient’. For example, we cannot fund every initiative, provide every variant of equipment or have unlimited funds for operational staff. All organisations must make the best use of their resources and there will always be a drive towards greater efficiencies.

The green line in Fig. 1 indicates this. Individually, there is only so much work which can be done and therefore workload pressures also play a part. If workload is too high, then overloads can result, and the work stream may break down, resulting in stopping some activities. Similarly, if there is too little work, individuals and teams may be ‘underloaded’ and there may also be safety incidents, often more critical. The failure of the organisation due to workload imbalance is shown by the blue line and the arrow shows the pressure to reduce workload.

Figure 1. A Safety II framework (adapted from Rasmussen, 1997).

Figure 1. A Safety II framework (adapted from Rasmussen, 1997).

Lastly, there are safety culture programmes, safety initiatives, assurance methods and other activities all pushing away from the safety line where an accident could occur. These activities ensure that we keep the operational environment safe.

These three pressures change constantly and the point where we operate will be in a different place from day to day and from minute to minute. Gaining an understanding of the dynamics of these stressors tactically is going to be key to supporting a safe operation especially when we know the frequency of serious adverse events is low and the complexity of large safety critical teams continues to grow.

It is for this reason the relatively new concept of Safety II may deliver improvements to safety. The following principles of Safety II need to be considered when developing this alternative perspective:

- Understand current performance, and how performance varies, to understand safety.

- Understand the pressures which cause the operating point to vary its position and drift towards danger.

- Develop the safety actions which will counter this increased pressure.

- Understand the trade-offs which are made in the operation to support efficiency, workload, and safety.

- Understand the gap between work as imagined and work as done.

- Understand what actions we take to anticipate risk and whether we are approaching our safety margins.

Alternative safety observation methodologies have therefore been developed to examine these issues, known as the Day-2-Day Safety Survey approach. These safety survey methods of the operational environment have several things in common:

- They focus on safety improvement.

- They are ‘over the shoulder’ observations by trained observers.

- The observations are confidential and nonpunitive.

- The observations focus on the whole system not individuals per se.

- They are periodically recurring rather than continuous programmes.

Day-to-day safety survey measures can be captured from everyday operations and include positive indicators of safety. These indicators will enable safety performance to be better understood over a short period of time and provide a means of obtaining rapid feedback on the impact of safety improvement actions. They will also complement the analysis of incident data and provide a better understanding of safety performance, enabling proactive safety management.

In NATS, and other related high-risk, high-performance industries, this approach is associated with the philosophy of Safety II, which emphasises how operational staff ‘do things well’, was developed and has successfully evolved over the last ten years.

The following paragraphs explain this methodology and its application in aviation and medicine.

Experience from air traffic management and beyond

Amongst the myriad of non-technical behaviours utilised by air traffic controllers (ATCs), visual scanning has long been of interest to human performance and safety specialists. In the ATC environment, poor visual scanning is thought to be an aggravating factor in a variety of errors. Visually, it can lead to controllers not seeing or miss-seeing an element of the visual scene, eg a conflict or misidentifying an aircraft. There are several reasons as to why this may occur, including tunnelling of the visual field, expectation, and distraction. This situation can also be exacerbated by the controller being over or underloaded. Poor scanning is also thought to affect judgement, planning and decision-making as these actions are dependent on the quality of information that is assimilated in the perception stage of information capture. In the dynamic world of air traffic control, missing a critical piece of visual information can have serious consequences, leading to operational errors.

USING A MORE PROACTIVE APPROACH TO ‘DESIGNING IN’ SAFETY PERFORMANCE ENABLED A 70% REDUCTION IN NATS’ SAFETY RISK INDEX BETWEEN 2007 AND 2010

The NATS Day-to-Day (D2D) Safety Observation programme recognises ‘effective’ visual scanning techniques as a strong mitigation against certain perception errors. In instances where data from D2D observations reveals that positive behaviours are less frequently seen, human factors specialists work closely with safety managers and operational staff to prioritise and define safety improvement activities. Utilising this early, indicative data, activities were designed and developed, which formed the basis of new training packages for controllers and trainees and also assisted in the design and implementation of new systems. As a result of these types of activities, an increase in the presence of positive scanning behaviours was noted. Furthermore, it was also realised that, where D2D and incident data were correlated, improvements in the day-to-day operational performance reduced incident rates.

Having now been utilised for over ten years in NATS, several safety improvement activities at aerodrome, approach and en route centres/units have been carried out as a result of the findings from the Day-to-Day Safety Observation programme. Early identification of ‘weak signals’ allows operational units and teams to put in place proactive and preventative safety measures. Examples within NATS include: the development of handover checklists, updates to procedures, telephone discipline, defensive controlling simulations and hearback/readback exercises for use in training. The findings are also being used to inform the development of future changes to both technology and airspace. Using a more proactive approach to ‘designing in’ safety performance enabled a 70% reduction in NATS’ Safety Risk Index between 2007 and 2010, which was a weighted average of all significant incidents.

Programme developments have also allowed the extension of day-to-day safety observations into the flight deck of two of the United Kingdom’s major airline carriers, adjacent ATC units, and ground handling staff. Numerous recommendations have resulted from these observations relating to training, procedure changes and equipment enhancements.

NATS

NATS

Further developments

In terms of human performance issues, ATM does not differ from other industries in which individuals work in highly coupled teams within high-risk, high-reliability environments. Highly-coupled complex organisations demand that individuals follow well-founded rules and procedures and have clear, concise and often standardised communication protocols. The individuals in these situations also rely on others to work in close collaboration with little room for errors which are unrecoverable. Although in many cases individuals work on their own individual tasks, they continuously interact and co-ordinate their activities which are jointly monitored and supported where appropriate. These characteristics can be found in all aviation situations, as well as construction, transport, emergency response, nuclear and medicine. It is for this reason that the approach and method described is so successful.

Typically, therefore, in the last few years many further developments have evolved, both in aviation and in medicine. Observation criteria have now been developed for the following situations:

- standard human performance behaviours

- team-working

- students within college training

- on-the-job training instruction

- supervisory activities within live operations

- intra-team co-ordination

- inter-unit/centre co-ordination, including across international interface sectors

- new technology simulations in live operations

- flight deck operations, across all flight phases

- flight deck interface operations, including with cabin and ground crews

- communication and co-ordination between aerodrome ground handling teams

- clinical processes in specialist blood and organ transplant teams

This approach can be used in two ways – firstly by organisations, such as NATS, who want to monitor their safety status on a continuous basis and compare the results from one time period to another. This has the advantage of also monitoring the efficacy of improvement activities. Secondly, this activity has also been used when an organisation believes there has been an increase in safety data in a specific operational area, such as an increase of events associated with airport or runway occurrences or a particular flight phase in an airline.

Focusing on observing the presence of ‘good behaviours’ allows us to build a picture of where our latent risks in the system may be, as well as including positive indicators of safety.

However, it should also be realised that the latent risks in a system are complex and fluid, and every opportunity should be explored to view and identify these risks from differing perspectives to assist our understanding and subsequent safety management. The competency of individuals, as part of the system, can be valuable information and allows us to understand the manifestation of latent risk. This is only meaningful, however, if there are complementary methods of performance standards which include measurements of capability and confidence.

These indicators, among others, enable safety performance to be better understood in a proactive manner, allowing for a better appreciation of safety performance, particularly for front-line operational staff.

NATS

NATS Figure 1. A Safety II framework (adapted from Rasmussen, 1997).

Figure 1. A Safety II framework (adapted from Rasmussen, 1997).