AIR TRANSPORT 1921 Channel air transport RAeS position paper

100 years of civil aviation safety thought-leadership

One hundred years ago, in 1921, the RAeS published a position paper on the design of a future British civil aircraft to fly passengers between London and Paris. BILL READ FRAeS and TONY PILMER from the National Aerospace Library consider the historical reasons why such an aircraft was needed and the insights, both past and present, which the paper provides into the safe and reliable development of a new form of passenger transport.

RAeS/NAL

RAeS/NAL

One hundred years ago, the Safety and Economy Committee of the Council of the Royal Aeronautical Society published a position paper on the ‘type of engine and mechanical arrangements required for the safe and economical working of an aeroplane carrying mails and passengers between London and Paris’. The report provides interesting insights, not only on the contemporary state of aeronautical engineering but also in the safe development of new technology in the early days of the development of commercial airlines. It had also been intended to report on an aircraft design for a 500-mile route but this plan was dropped as ‘such benefit as might result would be greater if the report were produced at an early date.’

From this remark it can be deduced that there was some urgency in wanting to get the report published so that work could be started on an actual design. The reason for this urgency becomes apparent when we look at the early history of British commercial aviation.

The dream of a British civil aviation industry

George Holt Thomas (RAeS NAL)In the depths of WW1, George Holt Thomas, the former publisher and then driving force behind Airco, one of Britain’s largest aircraft companies, saw that delivering mail and passengers by air would not only become a commercial proposition but would be of key importance to the future of the British Empire.

George Holt Thomas (RAeS NAL)In the depths of WW1, George Holt Thomas, the former publisher and then driving force behind Airco, one of Britain’s largest aircraft companies, saw that delivering mail and passengers by air would not only become a commercial proposition but would be of key importance to the future of the British Empire.

RAeS 1921 Position Paper. RAeS/NAL

RAeS 1921 Position Paper. RAeS/NAL

As early as November 1916, he had established his own airline, Aircraft Transport & Travel (AT&T). Only four days after the Armistice, AT&T announced that it was making arrangements to establish a route between the Ritz Hotel in London and the Ritz in Paris.

Unsurprisingly, Holt Thomas looked towards Airco and its designer, Geoffrey de Havilland, for aircraft. Airco had experience of converting the rear cockpit of the D.H.4 bomber into a cabin to create the D.H.4A civil aircraft for the RAF and these were also adopted by AT&T.

Airco similarly converted D.H.9s into civil aircraft for AT&T and de Havilland also used spare parts for his D.H.16 bomber to create a four-passenger variant.

Airlines take to the air

Though the first scheduled cross-channel trips would have to wait until the final peace treaty was signed and air international regulations agreed in 1919, four main companies lined up to become Britain’s first airlines.

AT&T was first in the air on 1 May 1919, though its first cross-country run started in disaster with its DH.9 crashing near Portsmouth. AT&T was then followed out of London’s aerodrome at Hounslow by Avro Hire Co on 24 May, British Daimler Air Hire Co on 7 June and Handley Page Transport Co on 14 June.

AT&T’s two main British competitors on the London to Paris route were Handley Page, which converted some of its wartime aircraft for civil use and S. J. Instone, a shipping company which started to use aircraft to transport staff and documents but decided to open up its service to the paying public in February 1920.

It used a selection of aircraft the wartime designs of Vickers Vimy and de Havilland D.H.4A, as well as Westland’s and de Havilland’s first purpose-built civil aircraft, the Limousine and D.H.18. respectively.

The opening and closing of the London-Paris route

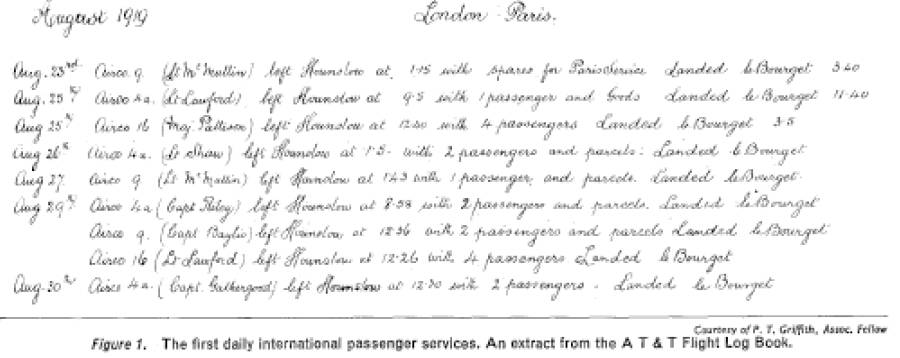

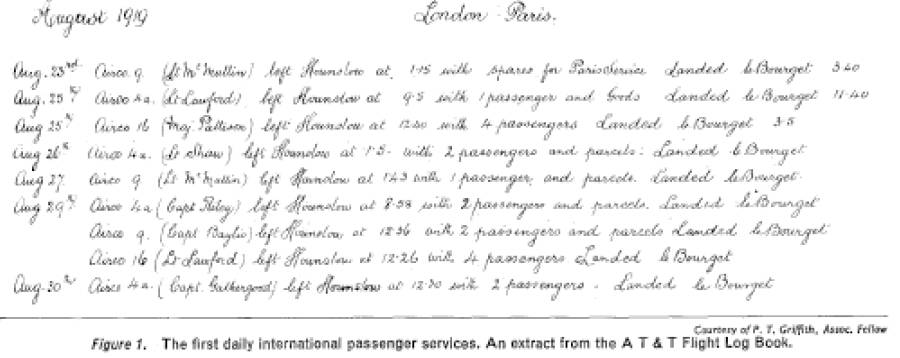

The official opening of the cross-channel route was scheduled for 25 August 1919. Once again AT&T was in the air first with the world’s first international regular scheduled flight, taking off at 12.30pm (a date which British Airways choose to celebrate as the beginning of its centenary in 2019).

The creation of British civil aviation was not all plain sailing. Two AT&T D.H.4As encountered problems in the winter of 1919. The aircraft came down in the English Channel without loss of life, after which both the pilot and his passenger were killed in an accident over Coulsdon Common in Surrey. Handley Page also experienced a crash just after take-off the following winter in which the pilot, mechanic and two of the six passengers also lost their lives.

The de Havilland DH16. RAeS/NAL

The de Havilland DH16. RAeS/NAL

Initially, it appeared that one or two of the new routes would turn the corner financially, which was fortunate, as the British government did not look kindly towards the fledgling industry. On 11 March 1920 the Secretary of State for Air, Winston Churchill, underlined the government’s stance when he told the House of Commons that: “Civil Aviation must fly by itself; the government cannot possibly hold it up to the air”.

However, the new airlines’ luck did not hold, as their continental rivals began to receive state aid. The losses mounted and the British companies stopped flying. However, the suspension of the British service across the channel did not last long. The government did a U-turn and made £60,000 available to subsidise the route.

IT&T London-Paris August 1919 flight log book. RAeS/NAL

IT&T London-Paris August 1919 flight log book. RAeS/NAL

The Royal Aeronautical Society to the rescue

It was at this point that the Council of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain, by then renamed the Royal Aeronautical Society, decided to bring together a number of their leading experts to ‘discuss what is required to ensure the safe and economical working of an aeroplane carrying mails and passengers between London and Paris’.

The references to ‘safe and economical working’ now become clearer, as a response to the air crashes of 1919 and the financial disasters of 1920 and 1921. What was needed was an aircraft design which could carry passengers safely, was reliable in service and economical to operate.

The first AT&T London-Paris flight. RAeS/NAL

The first AT&T London-Paris flight. RAeS/NAL

The fact that there was a need for new aircraft designs is borne out by an article written by Sir Alan Cobham at the time of the RAeS’ centenary in 1966. “In the early 20s, as far as I can remember, there was little worthwhile development in new types of aircraft. Conversions of wartime aircraft to meet the demands of civil aviation, seemed to be the vogue of the day.”

Cobham also commented on aircraft safety and reliability: “In the early days of flying, one lived as a pilot by virtue of one’s ability to accomplish a forced landing, because one never knew ‘from one moment to another’ when the engine would fail to operate. Anything could happen – a faulty propeller, a bad fuel system, pumps that packed up, broken inlet valves, broken valve springs, conrods broken and even a split crank case.”

The Safety and Economy Committee was formed in February 1921 and worked quickly. Within three months the report was put before the Council, adopted and it was decided that it should be published.

The majority of the report concentrates on the technical details of suitable aero engines, followed by some brief remarks on the design of the aircraft and concluding with a few comments on the requirements of the flight itself.

While it was the opinion of the committee that contemporary aero engines were largely reliable, they were still at risk of failure due to other factors, such as poor installation, lack of cleanliness, oil leaks, or faulty fuel feeds and filters. The report recommends that civil aircraft should adopt pressurised fuel systems rather than gravity feed, which would increase fire safety by having fuel tanks in the wings rather than inside the fuselage.

One cause of engine failure was due to faulty valves and springs which were not always a uniform size. Present day quality control managers would no doubt be horrified to learn that the procedure for inspecting new springs in 1921 relied on visual inspections from skilled manual workers. The RAeS recommended that research was conducted on the scientifically precise treatment of the spring material to bring mechanical differences within small and reliable limits of variation.

Fuel and compression ratios

It is also perhaps surprising to learn that fuel gauges were not yet standard equipment. The report states that: ‘The pilot must have knowledge at any given moment of the amount of fuel in his tanks… Urgent efforts should be made to produce a satisfactory distance-reading petrol gauge’.

Safety

The committee also recommended that future aircraft should be fitted with a mechanical engine starter, observing that the ‘present unsatisfactory method of starting the engine by swinging the airscrew’ is an ‘inefficient and dangerous proceeding’.

Ease of maintenance

Ease of maintenance is also considered, with the recommendation that ‘engine cowlings should be completely dismountable or replaceable in three or four minutes without the use of tools, and in such a way as to leave the engine and accessories completely clear.’ Magnetos should also be readily removable and easily replaced.

Sharing information

It was also recommended that the aeroplane designer should give as much information as possible to the engine designer on their proposed designs, since ‘the engine takes much longer to evolve than the aircraft’. In more recent times, an engine design is often ready before the aircraft but the suggestion for more communication and collaboration between designers and manufacturers is an interesting foretaste of the present ‘digital design’ and ‘virtual twin’ interactive aircraft testing and design methods of the 21st Century.

One engine or two?

There was some debate within the committee over whether future commercial aircraft should have one or two propellers. It was felt that, for safety reasons, there should be two engines so that one could continue working in the event of the failure of another. However, there was no clear preference over whether the two engines should each power separate propellers or have them coupled together to one propeller (a design feature used to power rotors in many modern helicopters).

The Croydon air traffic control tower. Brendan and Ruth McCartney/Wikimedia

The Croydon air traffic control tower. Brendan and Ruth McCartney/Wikimedia

Navigation and air traffic control

The paper also issued an early call for the creation of what eventually evolved into air traffic control, saying that there was a need to establish ‘some means to warn pilots of each other’s presence’.

Again highlighting the need for a future ATC system was a recommendation that pilots should have the means to communicate with the ground by wireless so that warnings could be issued regarding local fog or cloud: ‘The committee strongly recommend that a complete organisation of meterological warnings by wireless should be developed.’

The emergency exits are here – or you can just go out through the wall

The committee briefly commented on the emergency evacuation of aircraft, a recommendation that is again worth quoting in full: ‘It is not always possible for passengers to make their exit from aeroplanes in certain positions, in the event of a crash and even where it may be possible to escape by making a hole in the fabric covering the fuselage, experience shows that passengers are not aware of this fact. It is recommended that the provision of emergency exits for rapidly discharging passengers in the event of a crash, in whatever position the aeroplane may be and the notification of such means of egress, should be made compulsory.’

Fire precautions on aircraft were also highlighted as an important factor but not included as a subject for discussion.

Finally, because the aircraft was going to operate across the Channel, the committee included a recommendation that the design include ‘provision for safe alighting on water and for the flotation of the aeroplane for at least half an hour, coupled with some means of signalling for assistance.’

What happened next

The RAeS position paper was mostly well received. The RAeS 1922 Annual Report heralded it as a ‘valuable report…(which) was most favourably received’. However, the test of the report was whether the findings were adopted by those designing the next generation of aircraft.

The new generation of aircraft

Instone and Daimler, which was born from the ashes of AT&T, relied on de Havilland’s new civil aircraft, the D.H. 34. Though its Napier Lion engine did come out as a unit, there was only room for nine passengers and the pilot’s view ahead was partially obscured by the engine’s radiator header-tank.

Handley Page relied on the Handley Page W.8 and its variants. These were first flown in 1919 but only entered service in October 1921. Though the location of the fuel tanks was moved from the engine nacelles after the publication of the committee’s report, they did not follow their recommendations to put them in the wings but chose to put them on top of the wings.

Instone also purchased three Vickers 61 Vulcans, which was quickly nicknamed ‘The Flying Pig’. However, perhaps the airlines heeded the RAeS report more than the designers, as Instone ordered extra equipment, such as air flotation bags and pneumatic safety belts.

RAeS/NAL

RAeS/NAL

An effect on ATC?

Perhaps the quickest recommendation to come into force concerned the committee’s suggestion that radio should be used to bring aircraft into land. On 3 November 1921, Flight’s Croydon Aerodrome reporter told readers that: ‘Tests on a new wireless apparatus which has been erected in the control-tower were carried out on Saturday with extremely satisfactory results. This apparatus is for guiding aeroplanes once they have approached the air-station on days when visibility is bad and it is difficult to pick out landmarks.’

Vickers Vulcan Type 61 G-EBET. RAeS/NAL

Vickers Vulcan Type 61 G-EBET. RAeS/NAL

Losses mount up

Airline finances continued to decline in 1921. The government’s predictions on cross-channel traffic were overly optimistic and Instone and Handley Page lost £5,398 between them. A longer-term solution was required and, from 1 April 1922, a £200,000 annual government subsidy was given to support the London to Paris route, though this was measly compared to the £1.3m of subsidy given by the French government.

However, even with the new scheme, losses continued to mount up. The longer-term solution was to combine the airlines into one large company backed with a ten-year subsidy from the government and, on 1 April 1924, Imperial Airways was born.

100 years ago, the RAeS was at the vanguard of thought leadership in improving aviation safety. Today, it and its Specialist Groups continue this learned role to advance the art, science and engineering of aeronautics.

A longer version of this article is available online at the AEROSPACE Insight blog

RAeS/NAL

RAeS/NAL George Holt Thomas (RAeS NAL)In the depths of WW1, George Holt Thomas, the former publisher and then driving force behind Airco, one of Britain’s largest aircraft companies, saw that delivering mail and passengers by air would not only become a commercial proposition but would be of key importance to the future of the British Empire.

George Holt Thomas (RAeS NAL)In the depths of WW1, George Holt Thomas, the former publisher and then driving force behind Airco, one of Britain’s largest aircraft companies, saw that delivering mail and passengers by air would not only become a commercial proposition but would be of key importance to the future of the British Empire. RAeS 1921 Position Paper. RAeS/NAL

RAeS 1921 Position Paper. RAeS/NAL The de Havilland DH16. RAeS/NAL

The de Havilland DH16. RAeS/NAL IT&T London-Paris August 1919 flight log book. RAeS/NAL

IT&T London-Paris August 1919 flight log book. RAeS/NAL The first AT&T London-Paris flight. RAeS/NAL

The first AT&T London-Paris flight. RAeS/NAL