SPACEFLIGHT Education and training

The UK space skills gap

CATARINA BALDAIA, and ALEX GODFREY (RAeS Space Group ECS) along with JOSEPH DUDLEY and HEIDI THIEMANN (Space Skills Alliance) look at the results of a recent survey on the skills needed to allow the UK space sector to really take-off.

A young visitor to the RAeS HQ embarks upon her first space-focused training session. ESA / S. Corvaja

A young visitor to the RAeS HQ embarks upon her first space-focused training session. ESA / S. Corvaja

When Apollo 11 set off for the Moon, the average age of the people in mission control was just 26. The average age of everyone working at NASA at that point was 28. Most were hired on CVs alone: no psychometric or analytical test, no group exercises and, in many cases, no interviews. By contrast, today’s 26-year-olds are finishing graduate schemes and thinking about their next steps. Working on a mission of the same scale as Apollo is a five or ten-year career goal. Were the 26-year-olds of the 1960s more skilled than their modern counterparts? How can the UK space industry help produce another stellar crop of scientists and engineers? Have we missed the boat?

What is the current status of the sector?

There have been a few changes in the sector since Apollo. One of the most notable is that space is no longer only the preserve of governments and mega corporations. The commercial space sector has finally come of age – witness NASA’s commercial crew programme – and is growing at breakneck speed.

While NASA has always been popular, it is only in recent years that space in the UK has gone from an ugly duckling to a beautiful swan in the eyes of the media, public and government, thanks to the impact of Tim Peake’s launch and the possibility of domestic launch capabilities. Brexit is likely to intensify this focus as the government looks for post-breakup national success stories and exclusion from the EU Galileo satellite navigation system may force the creation of a homegrown replacement.

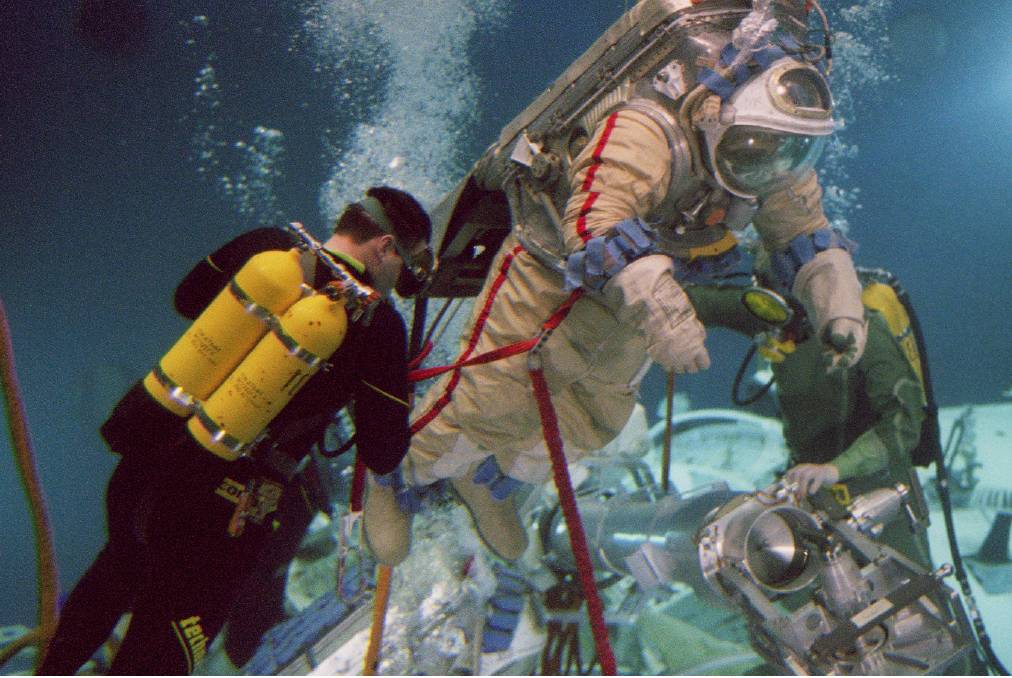

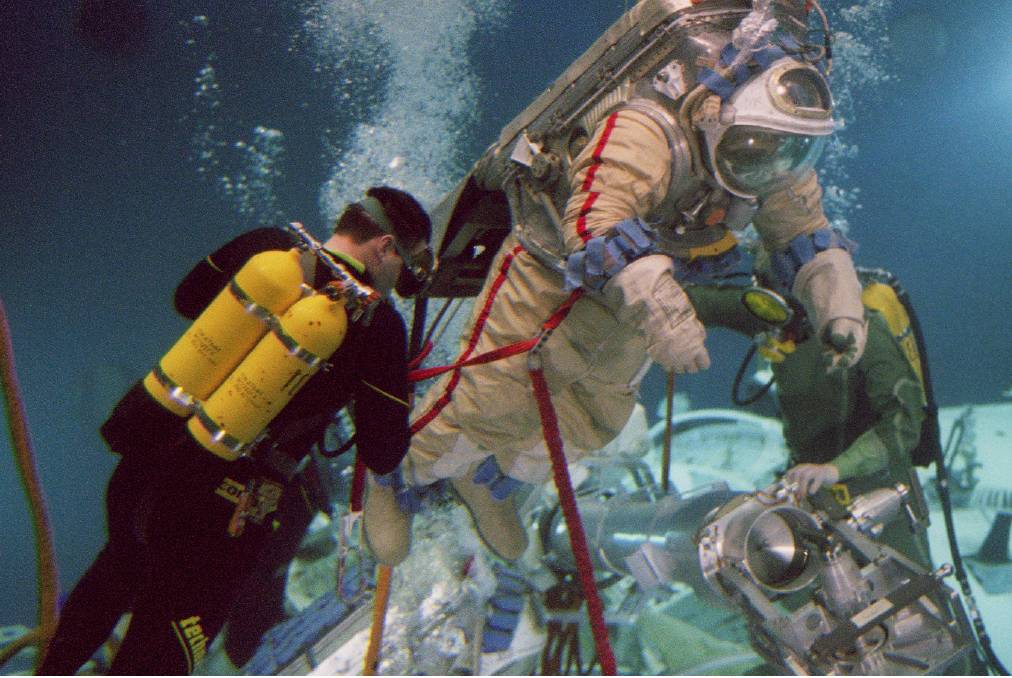

An ESA astronaut is involved in more advanced training.ESA / S. Corvaja

An ESA astronaut is involved in more advanced training.ESA / S. Corvaja

UK growth has been strongest in the downstream sector, which uses data from space for everything from farming to monitoring of criminals on probation. New technologies, such as better cameras, have enhanced the quality of data and machine learning has made it easier to process huge data sets. All this data has attracted tech companies, both big and small, and it is easier than ever to start a new technology company.

The sector set itself a goal of having a global market share of 10% by 2030, double its current share of around 6%. To achieve this, it will need to attract and retain many new recruits while fighting off intense competition from tech and other sectors (who pay a lot more). It will also need to navigate more stringent post-Brexit immigration rules.

What are the barriers to achieving growth?

The space skills shortage is well documented, most recently in the UK Space Agency’s Space Sector Skills Survey (S4), which found that more than half of companies found it difficult to recruit but it is not an easy subject to get to grips with.

One major challenge is the complex structure of the sector and the long list of highly specialised skills that it needs. A key quote from the S4 report is that there is ‘no obvious single focus for training … that would address a substantial proportion of the recruitment difficulties’.

Despite this, there are some broadly applicable skills which are in high demand, notably software, systems, and electronics engineering. Research by the Space Skills Alliance, last year found that half of all early career space jobs asked for software development skills. Catena Space, IN MANY a space training provider working with the Space Skills Alliance, also found that graduates would benefit from better understanding of the challenges of the space environment (for spacecraft design) and how to apply quality assurance standards, such as ECSS and ISO. The skills gaps are becoming clearer but how to resolve them in an efficient and timely manner is a much more challenging question.

In many ways, the space sector resembles the early tech sector and risks repeating the same mistakes if it takes too long to address its recruitment and retainment issues.

Initiatives introduced in recent years offer a model to learn from. ‘Zero to hero’ coding boot camps have helped stem the shortage of programmers, and MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) have promised similar rapid upskilling. Similar programmes could be implemented in the space sector. However, they rely on close collaboration between the industry and training providers. This is something the sector does not have enough of at the moment.

University challenge

Employers report that, though graduates are in rich supply, they often lack specific, relevant skills and experience because these are not being taught at universities. Portia Bowman, UK Innovation Manager at D-Orbit, says that: “It’s easy to recruit young people who are very capable but they don’t have the experience”. Despite the high demand for programming skills, not enough aerospace engineering courses include this as a core component.

IN MANY WAYS, THE SPACE SECTOR RESEMBLES THE EARLY TECH SECTOR, AND RISKS REPEATING THE SAME MISTAKES IF IT TAKES TOO LONG TO ADDRESS ITS RECRUITMENT AND RETAINMENT ISSUES

This is not helped by a shortage of opportunities to gain experience. Data collected from delegates to the National Student Space Conference in 2017 and 2018 shows that there is a high demand for internships and research placements which significantly outstrips the number of available positions. However this has improved in recent years with the growth of Satellite Applications Catapult’s Space Placements in Industry (SPIN) and student competitions, such as UKSEDS’ Olympus Rover Trials, a challenge to design, build and test miniature Mars rovers.

An unwillingness to take a chance on those without experience and to hire and train those from outside the sector compounds the problem. Those applying to work on Apollo could not have experience, as the space sector was too new an invention. NASA’s recruiters had to work with what they had and supported bright graduates to develop their skills and, in doing so, created the foundation of the modern industry. Today’s recruiters need to do the same.

Broadening talent diversity

Much of the tech sector’s problems were caused by its workaholic culture and rampant discrimination which put off almost anyone who did not fit the Mark Zuckerberg mould. A growing number of start-ups now consciously eschew Silicon Valley culture, expanding their talent pool by offering perks that appeal to working parents and funding programmes to train up those from under-represented backgrounds.

A NASA astronaut in training. NASA

A NASA astronaut in training. NASA

While the space sector’s culture is not as bad, there is still a lot of work to be done. Among those working on Apollo were many brilliant women and BAME representatives, including Margaret Hamilton, Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson, the latter three of Hidden Figures fame. Results from the 2020 Space Census show that a half century later, the UK space sector is overwhelmingly made up of straight white men.

Why? For starters, recruitment and retention are one end of a very leaky talent pipeline. Extensive research into STEM uptake and attitudes in schools have found that girls turn away from a career in science and engineering at a very early age and at every stage are less likely than their male counterparts to continue on a path to the sector.

This is a result of a range of factors, including lack of encouragement, gender stereotypes perpetuated widely in the media and by the industry, and toxic cultures within companies. The Space Census found that approximately 38% of women, 29% of BAME people and 15% of disabled people have experienced discrimination.

It did not help that two years ago, when astronauts Jessica Meir and Christina Koch were scheduled to conduct the first all-female spacewalk, the male-first thinking of much of the sector was revealed when NASA realised that it had not provided enough smaller space suits to fit both female astronauts. Meir was replaced by her male colleague, Nick Hague, a metaphor for recruitment everywhere.

The sector must do a better job of addressing these issues and proactively supporting efforts to get more people from under-represented groups into STEM. Outreach is not enough. Many studies have shown that the effects of one-off outreach activities are minimal compared to long-term in-school ones. If the sector is truly committed to closing this gap, then it needs to be funding STEM programmes with proven impact, not just those that make for the best publicity.

These programs need to be supported at the earliest point in a young person’s education. Some studies have found that even by the age of 7, children held stereotypical views on jobs. At this age, four times as many boys wanted to become engineers compared to girls. Early interventions can have a lasting impact and be a pivotal influence on a child’s perception of different occupations.

Improved reach

A huge amount of work has gone into raising awareness of space among school students and the public, most notably during the Principia campaign for Tim Peake’s launch. UKSEDS, the national student space society, has made space a much more visible career path, particularly through SpaceCareers.uk, a careers advice website and early career jobs board. Many of those students go on to participate in the SPIN programme, a vital pathway for gaining work experience.

When it comes to recruiting these graduates, the sector does itself no favours in the way it advertises. A Space Skills Alliance report on space job adverts found that, when rated against 10 best practice criteria shown to make jobs more attractive to underrepresented groups, the average advert scored just 54 out of 100, and only 8% of adverts scored 75 or more.

Better job adverts are an easy fix with impressive results. Thames Water rewrote an advert for sewage technicians and saw the proportion of female applicants increase from 8% to 46%.

Astronauts may still get the glory, but there is an ever expanding number of space careers and opportunities available for young people. Space Careers UK

Astronauts may still get the glory, but there is an ever expanding number of space careers and opportunities available for young people. Space Careers UK

Keeping talent in space

The talent pipeline extends well beyond recruitment however. The S4 report found that graduates tend to leave after a few years when they realise their skills have increased at a faster rate than their salary. This has led to a growing shortage of midlevel professionals and those who remain in the sector tend to get poached and hop between space companies on an almost annual basis.

The Census found that about 4% of people are in the process of changing jobs, 10% are actively looking and 32% are open to changing for the right opportunity. Together, that is almost half of the workforce.

There is a similar story in the United States. A 2016 report of the American space sector by the Society of Space Professionals International (SSPI) found that, of employees with one to five years of service, a whopping two thirds choose to change employers.

Why all this chopping and changing? This is a topic that needs more research but what evidence we do have points to poor working conditions. The Census found that approximately 14% of people have a bad work-life balance and minorities in the sector experience a high level of discrimination.

The cost to the sector of these recruitment and retention issues is substantial. Skills gaps hold back growth, delay work and increase workloads for the remaining staff (further compounding the problem). Time spent on the recruitment process and bringing new hires up to speed is also expensive and, without proactive steps, this problem will only intensify.

A contender from the UKSEDS’ Olympus Rover Trials. UKSED

A contender from the UKSEDS’ Olympus Rover Trials. UKSED

To properly tackle it, we need joined-up thinking between industry, government, and academia, and we need to learn from mistakes made elsewhere. Industry needs to be clearer about what their skills needs and expectations are, and academia and other training providers need to better match their courses to those needs. There is a role here for organisations like the Royal Aeronautical Society to act as a bridge and to ensure that the courses such organisations accredit are up to scratch. In addition, training courses and events in some of the unique challenges of space are needed from a variety of providers to support the upskilling of non-space sector entrants. This could be co-ordinated through a central portal which the UK Space Agency could support with modest resources.

There needs to be better support for long-term STEM initiatives in schools that address the early stages of the pipeline and more opportunities to gain experience. Programmes like SPIN aimed at graduates need to be expanded and equivalents for apprentices need to be developed, alongside pathways for engineers to advance in their careers without taking on management responsibility. Programmes like the Civil Service Fast Stream, designed specifically to get people quickly into leadership roles, offer possible approaches to addressing the shortage of mid-level professionals.

More inclusive job adverts will help broaden the pool of applicants and a greater focus on retention through better work environments and culture change will help these actions have a long-term impact. This is perhaps the hardest and least flashy task but one of the most important. Culture will not change of its own accord; it has to be deliberately and continuously developed through actions, not just a list of values at the top of the staff handbook. If it is not changed, it is easily replaced by the status quo, which is too often subtle (and less subtle) sexism and racism. We must not allow this to happen.

Looking ahead, beyond the stars

The coming decades promise to be an exciting time for our sector. Low-cost domestic launch will open up new markets and new opportunities. The challenges of space debris and climate change will be ever more pressing and together we will push the boundaries of science and technology even further, to the Moon and perhaps also to Mars.

To achieve all this, we need skilled people of all types from all backgrounds. That means we must open our sector to people we have not considered before. The 26-year-olds of the 1960s were not smarter, or more skilled, or better educated than today’s graduates; they were just all that was on offer. NASA had no choice but to take a risk, to trust that bright, hard working people properly supported can achieve extraordinary things.

We must take that same risk today. We again find ourselves with too few experienced hands and a wealth of smart and motivated youngsters willing and able to transform our industry and we must again trust them to achieve extraordinary things. Why? We have no choice.

It is not too late but our skills shortage is not going to resolve itself. We can sit and we can do nothing, rotating the same few highly qualified people from company to company, or we can learn from the mistakes others have made and choose to take action by engaging more closely with educators, by removing unnecessary barriers and by taking a chance on those who dare to dream.

When we do make it to Mars, perhaps mission control will once again be filled with 26-year-olds in whom we have chosen to put our faith in.

A young visitor to the RAeS HQ embarks upon her first space-focused training session. ESA / S. Corvaja

A young visitor to the RAeS HQ embarks upon her first space-focused training session. ESA / S. Corvaja An ESA astronaut is involved in more advanced training.ESA / S. Corvaja

An ESA astronaut is involved in more advanced training.ESA / S. Corvaja