SPACEFLIGHT Airbus Defence and Space

Local heroes

From CubeSats to Mars Rovers and from mega-constellations to deep-space probes, Airbus Defence and Space is the home team that makes up 70% of the UK’s fast-growing space sector with €1bn in revenue. TIM ROBINSON FRAeS profiles the powerhouse that is aiming for the stars.

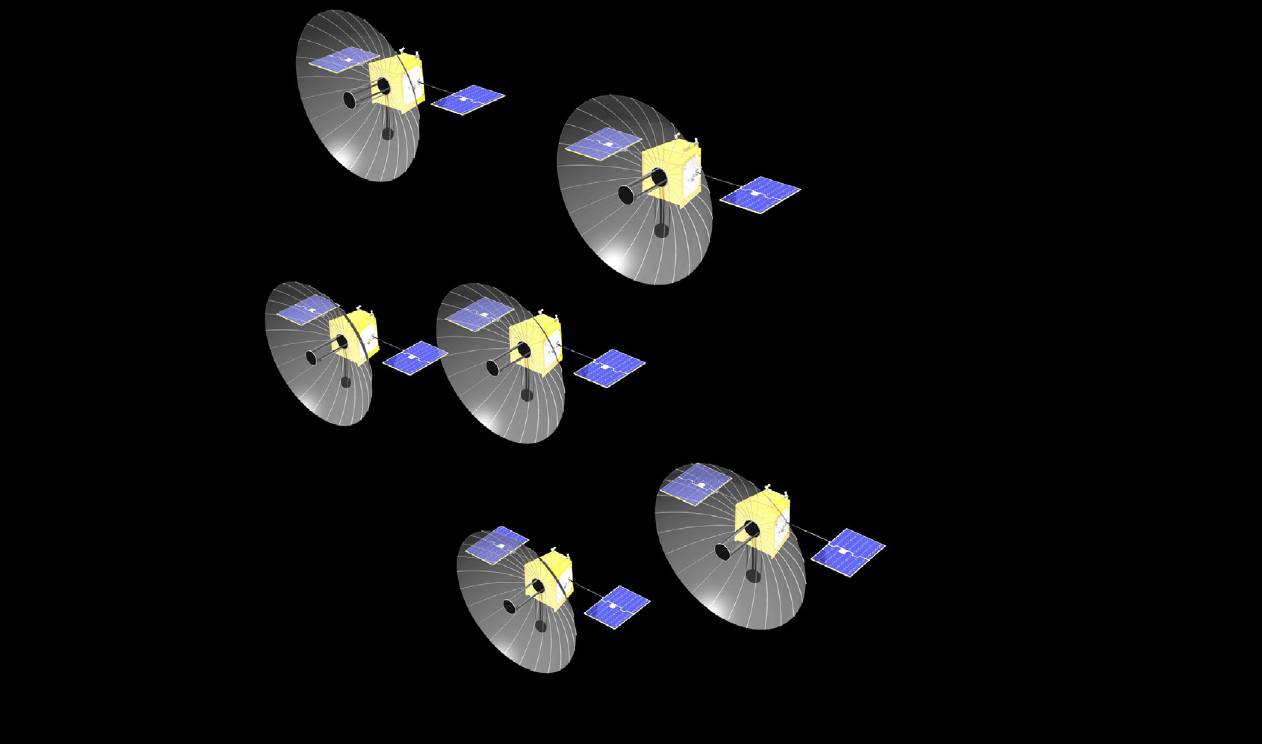

An artist’s impression of an Airbus Skynet 6A

satellite. Airbus

An artist’s impression of an Airbus Skynet 6A

satellite. Airbus

Think ‘Airbus UK’ and you might think airliner wings from Wazzzles, or perhaps, the A400M Atlas. However, the company, via its Defence & Space arm, is also the heart of Britain’s fast-growing space sector. Its capabilities range from commercial telecoms satellites, (every TV satellite broadcast in the UK comes from an Airbus-built satellite) to Mars Rovers, from Skynet secure military satcoms to CubeSats, mega-constellations, solar probes, weather monitoring and even space debris removal. Indeed, pick any European space mission and there is a good chance that AirbusDS has been involved in some way or other through either the UK or one of its European arms. The only space sector (at least in the UK) that it is not involved in, is launchers. Its business divides between 40% commercial, 40% defence and 20% institutional customers – giving it a ‘virtuous circle’ of sustainable business, according to Sarah Macken – Director of Business Development, Airbus Defence and Space, who says: “our commercial success gives choice to defence and hence underpins and helps make institutional campaigns more affordable.”

In the UK, the company is located in Stevenage (satellite design and manufacture), Portsmouth (payload, instruments and electronics), Corsham (comms services), Leicester and Guildford (mapping and imagery analysis, subsidiary SSTL – SmallSat design and manufacture). It has 6,500 highly skilled employees and is the second-largest aerospace and defence investor in the UK. This year, it has also taken on the UK’s first-ever ‘space apprentices’ – with 19 young people joining the company.

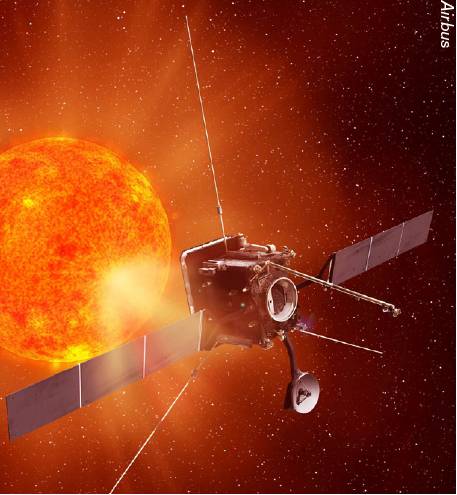

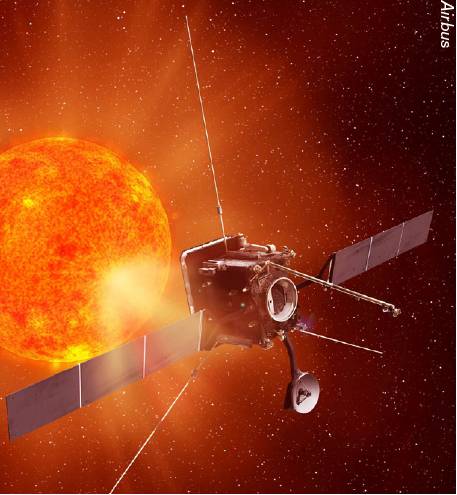

Solar Orbiter – built

by Airbus. Airbus

Solar Orbiter – built

by Airbus. Airbus

As part of the larger pan-European Airbus, there is no doubt that Brexit has had an effect on business, thanks to the high-profile exit of the UK from the EU’s Galileo satellite navigation programme. Macken admits: “Being out of that is eroding our capability in UK PNT (precision navigation and timing) – it was an area where we were leaders in the past. So, we are losing ground in that area at the moment. But, if we can get a national programme under way, then that could be reformed quite quickly.”

Yet as one door closes, more doors are potentially opening up, with the UK developing its own post-Galileo GNSS solution, the acquisition of OneWeb, a New Space Command, a shift to develop sovereign space ISR capabilities, upcoming National Space Strategy and UK spaceports – making this the most exciting time for Britain’s space sector.

Let’s take a look across Airbus’ space portfolio

Telecommunications satellites

Much of the ‘bread and butter’ of Airbus’ commercial business has been from telecoms satellites, ranging from OneSat to the new reprogrammable Eurostar Neo and a multimission Arrow – a new low-cost platform derived from the OneWeb satellite. Its Eurostar Neo features electric propulsion, allowing a larger payload and a digital processor – enabling the satellite to be reprogrammed throughout its life. Despite a tough market for GEO telecoms satellites, Airbus has sold eight in the past two years, the most recent one being a OneSat platform to Japan’s SKY Perfect JSAT. The company now has four full-electric satellites operational in orbit and 17 more electric telecommunication satellites under construction.

Manufacturing of a BIOMASS satellite at Airbus’ Stevenage factory. Airbus Defence and Space

Manufacturing of a BIOMASS satellite at Airbus’ Stevenage factory. Airbus Defence and Space

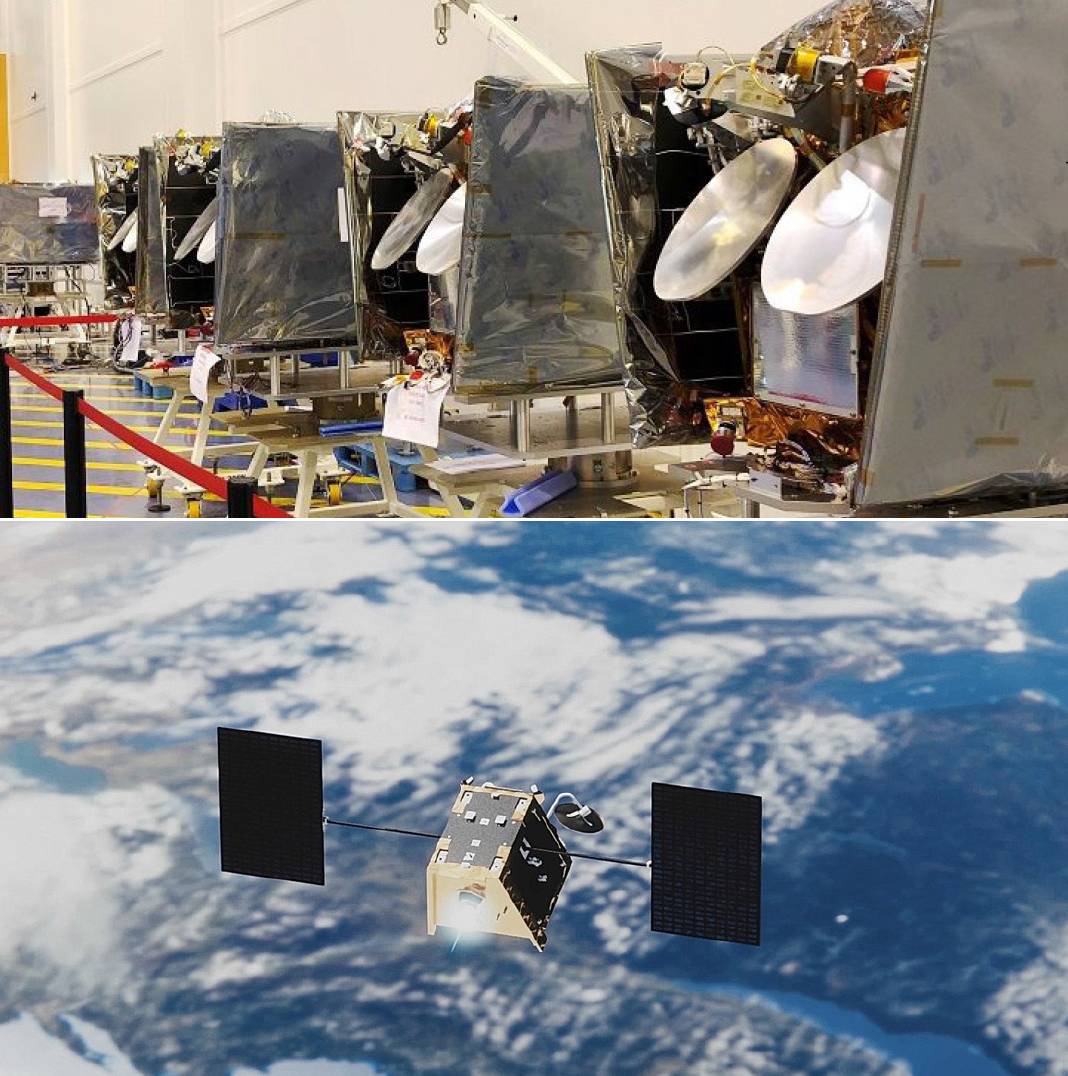

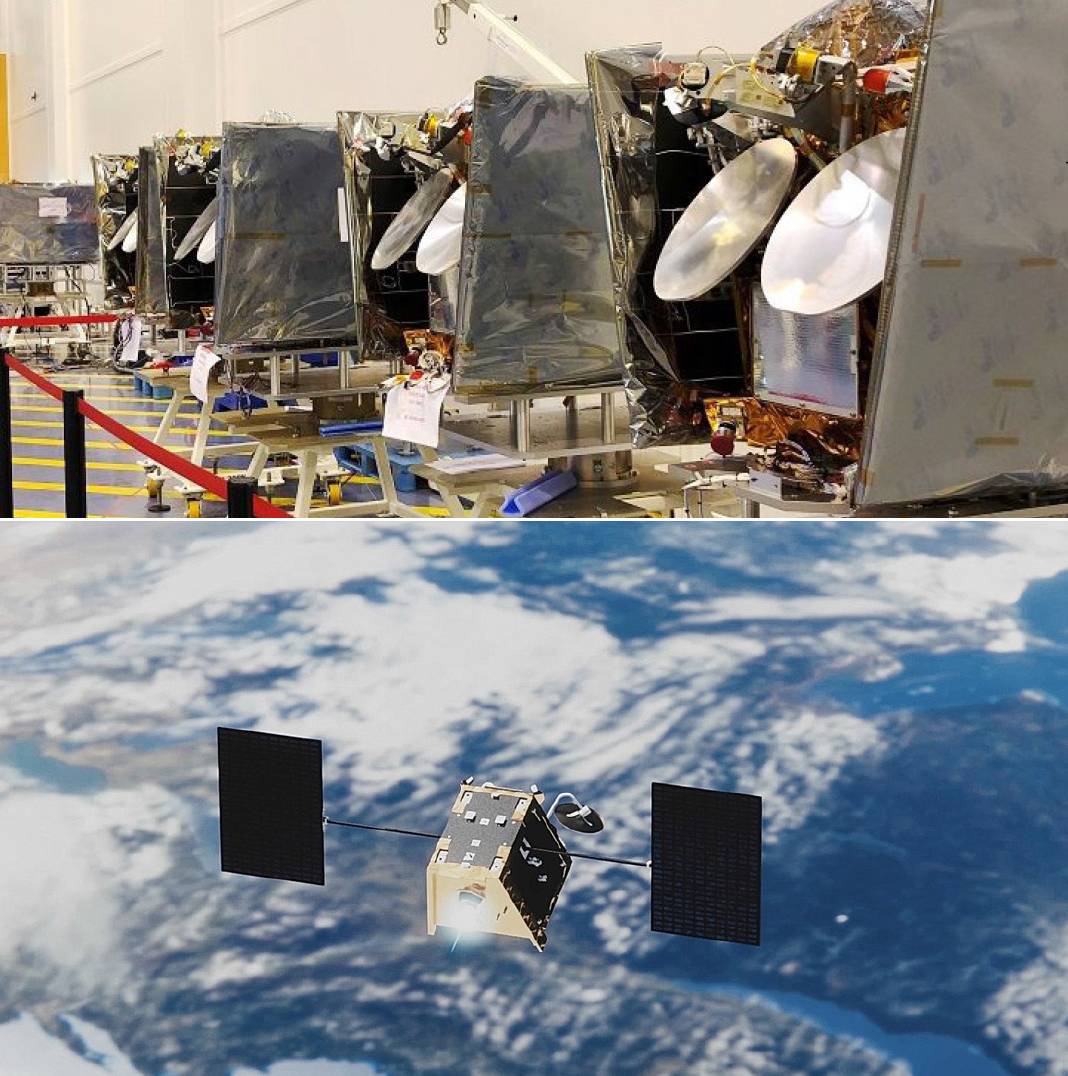

OneWeb – a fantastic opportunity?

Airbus also is responsible for building the OneWeb broadband satellite mega-constellation, which eventually aims to field a giant network of 6,000+ small satellites in LEO. From its factory in Florida, Airbus is pioneering the mass production of low-cost broadband satellites, leveraging decades of experience in optimising production lines for airliners.

Rescued from bankruptcy by the UK government and an Indian billionaire, Airbus is keen to highlight the future potential of this strategic asset for Britain – with multiple applications that go beyond its already immense value as an LEO broadband constellation able to bring low-cost high-speed connectivity to remote regions. “I think the UK have got a fantastic opportunity, taking ownership of one of the first mega-constellation providers,” says Airbus’ Macken, adding: “OneWeb has really spearheaded a new era”.

Airbus believes that OneWeb satellites, fitted with hosted precision navigation payloads (PNT), could provide low-latency, GNSS services with 20cm accuracy – providing the UK with a highly resilient and unique satnav alternative to Galileo.

As UK Space Director Harvey Smyth notes of any UK Galileo replacement: “We don’t want to copy GNSS or Galileo, with 24 satellites in MEO – we want to do things in a different way, so that we can offer meaningful resilience to others,” adding: “that would give us a seat at the table”.

PNT payloads and the low-latency connectivity of a OneWeb comms/GNSS would not just benefit military customers, says Airbus, but could also help unlock the revolution of a 5G/Internet of Things (IoT) society, where pinpoint accuracy and broadband connectivity could enable self-driving cars, package delivery drones and urban air mobility (UAM).

The company also foresees that the OneWeb LEO constellation, linked in a ‘mesh’ network with GEO Skynet military communications satellites, could provide highly resilient and superfast connectivity for UK forces and boost critical national infrastructure.

Instead of ground stations providing a two-way uplink/downlink of getting data or a message to commanders, a combination of OneWeb and Skynet satellites could see the message routed among different nodes to optimise speed and security – turning space into multi-node ‘Internet’ or ‘Combat Cloud’. Airbus has already trialed conformal antennas on the A400M and in the future it is likely that similar technology will make it onto Tempest. That then, could potentially enable a Tempest pilot on the other side of the world to transmit HD targeting imagery to HQ in London, or receive moving satellite video directly into the cockpit.

Airbus also proposes that, while Gen 1 satellites would be built in Florida, a Gen 2 production line could be brought to the UK. Says Macken: “For Generation Two, we’re committed to delivering that in the UK and having a production line based here.” Opening such an ‘Industry 4.0’ mass-production satellite factory in the UK (with potentially the ability to pull satellites off this line to upgrade and modify them with other sovereign payloads, such as navigation or climate) would thus give the UK a highly valuable industrial asset in the ‘New Space’ race.

Allen Antrobus, Director Military Space, Airbus Defence and Space, agrees on the wider potential of OneWeb: “Can you now bring mass manufacturing to the UK and really put our stamp on the global stage? Can we do something different with PNT you know, or are we just going to leave it to the Americans again?” Indeed, the idea of leveraging commercial LEO constellations, with short design cycles, mass production and economies of scale, for military applications is something that the US is already working on via DARPA’s Blackjack programme.

While the rescue of OneWeb by the UK government has drawn criticism in some quarters, the UK now has a potentially highly valuable strategic space asset of soft power and technology in a stake in a mega-constellation. (It is notable that both China and now the EU are now mulling developing their own mega-constellations – as well as the behemoth that is SpaceX’s Starlink network.)

Upper: The first satellites aligned in the cleanroom at Airbus Toulouse site, ready for shipment. Airbus Defence and Space Lower: A OneWeb satellite. OneWeb.

Upper: The first satellites aligned in the cleanroom at Airbus Toulouse site, ready for shipment. Airbus Defence and Space Lower: A OneWeb satellite. OneWeb.

Skynet and beyond

In military space, Airbus has built up a formidable reputation with its military Skynet communication satellites, which provide robust and secure communications for UK (and other allied forces). From early beginnings as Marconi, BAe and EADS Astrium, the latest Airbus Skynet 5 series satellites were launched in 2007 as a PFI (private finance initiative) with Airbus providing secure communications to the MoD as a service.

However, the current Skynet service contract is now set to end in August 2022 and, with it, the UK MoD is seeking to shake up the way it procures military satcoms – with the aim of doing more ‘inhouse’, growing its own space cadre and knowledge base and splitting the contract into satellites themselves (Enduring Capability) and ground stations (Service Delivery Wrap) – which sees four consortiums bidding to deliver the service.

To that end, MoD has already placed a $630m contract for a Skynet 6A ‘gapfiller’ satellite, designed to bridge the gap between Skynet 5 and a larger £6bn follow-on Skynet EC at the end of the decade. Even though it is officially a ‘gapfiller’, Skynet 6A, set to launch in 2025, is a significant leap in capability with a full digital signal processor (DSP) and “over three times the capacity and capability of Skynet 5”, says, Rick Greenwood, VP Engineering and Operations, Airbus Secure Defence and Space.

While the full requirements of a next-gen Skynet EC capability are yet to be set in stone, there are already hints that the MoD is looking for a more connected, more interoperable, more diverse, more protected, more resilient and higher bandwidth solution than previous satellites. Greenwood foresees a move to higher frequency military Ka bands – allowing for smaller ground terminals and conformal antennas.

On resilience, Airbus is now actively considering how to make high-value assets like Skynet EC more protected – not just from EW, cyber or jamming but potentially kinetic attacks. Greenwood says that could perhaps take the form of equipping them with sensors, such as cameras, to watch for rogue satellites that may attempt to close with them. Another layer of protection might be in equipping these satellites with aircraft-like RWR (radar warning receivers) which again could incidate whether tracking or a hostile satellite had ‘locked-on’.

Finally, Airbus is mulling a concept to provide high-value military satellites with orbital guardians – or ‘bodyguard’ satellites. These unarmed smaller satellites would act as roving ‘football defenders’, moving in between unfriendly satellites attempting to close with their charge by blocking their approach. In extremis, a ‘bodyguard satellite’ could also put itself in the path of a kinetic or ramming attack from a hostile satellite. Although ‘bodyguard satellites’ sounds like science fiction, Greenwood says: “The technology is there now – it’s just the will and the money”.

Put together, these measures could vastly improve the survivability and protection of these next-generation military space assets in a more contested future, yet remain essentially defensive in purpose.

While Skynet already has an international dimension, (the US DoD is the biggest user after UK MoD), Airbus also believes that there is an opportunity to export Skynet technology to Australia, which is now launching a search for a new ‘defence satellite communications system’ under a $7bn JP 9102 programme.

The Skynet 5 satellite Teleport ground station at North Colerne, Wiltshire, UK. Airbus Defence and Space

The Skynet 5 satellite Teleport ground station at North Colerne, Wiltshire, UK. Airbus Defence and Space

SSTL – the pioneers of ‘New Space’

Over the past years, there has been much excitement around ‘New Space’ companies which range from launch companies (most notably SpaceX) to space tourism, to CubeSat developers and even companies whose whole business model relies on satellite-derived data – such as Uber. Yet it is often forgotten, that the ‘New Space’ revolution of small, cheaper satellites began in the UK, when in 1985 Surrey Satellites Ltd (SSTL) was formed as a tech spin-off from the University of Surrey. Since acquired by Airbus in 2008, SSTL has continued to pioneer the design and manufacture of small affordable satellites and has seen its business grow from strength to strength, developing satellites that range from international disaster monitoring to space debris removal, from the NovaSAR-1 radar satellites, to the RAF’s first satellite – Carbonite-2, which was launched in 2018 after only eight months.

With its expertise in imaging and Earth observation satellites, SSTL is also set to be critical in a seismic change in the UK developing its own national sovereign ISR capability – and is part of RAF’s Team Artemis, launched in 2019, which aims to fast-track a small satellite constellation. This could see further Carbonite demonstrator satellites include SAR radar and infrared sensors.

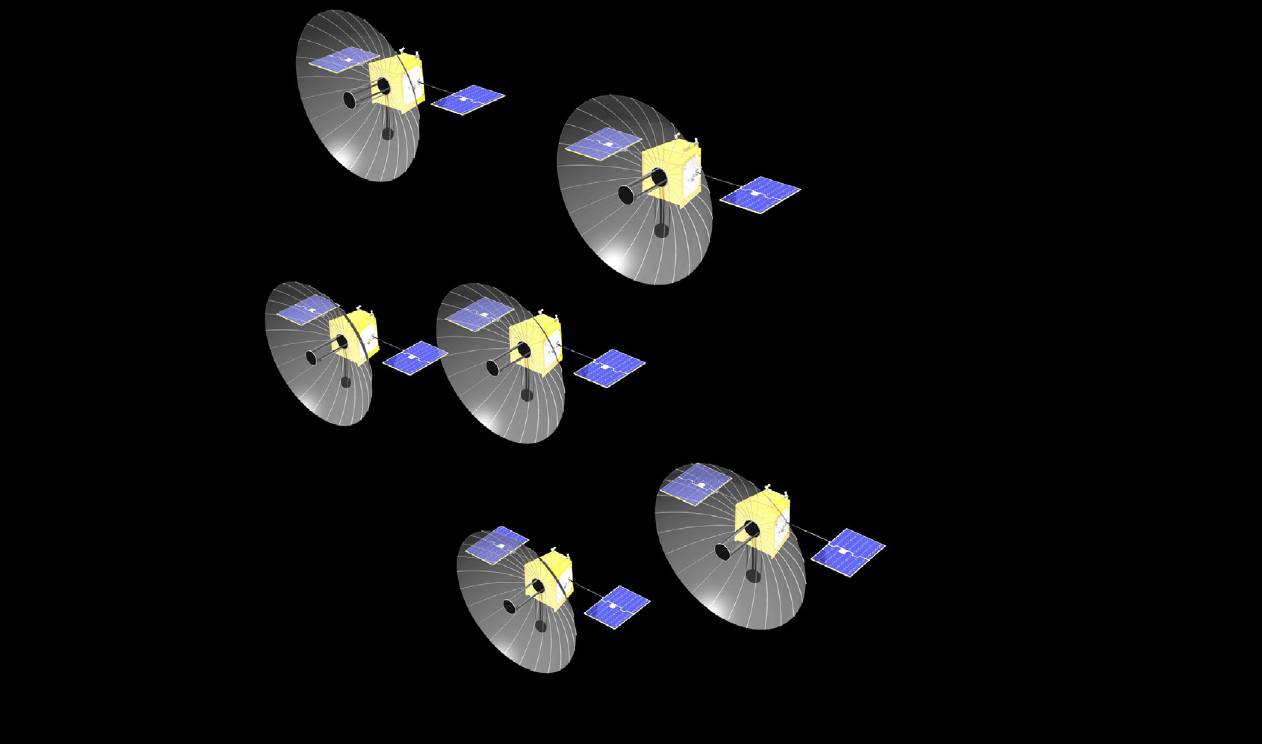

Meanwhile, parent company AirbusDS itself has won a design study for DSTL’s Project Oberon which sees a constellation of small ultra-high-resolution radar satellites. These would be equipped with RF receivers allowing SAR imagery to be fused with the location of electronic emissions.

SSTL is also looking further into deep space with the first-ever commercial Lunar communications satellite – Lunar Pathfinder, which will help unlock low-cost communications to the Moon for a multitude of national and private missions that are expected to develop as part of Lunar Gateway, NASA’s Artemis and other initiatives.

Finally, SSTL is also positioning itself for what founder Sir Martin Sweeting describes as the biggest gamechanger in the next decade – in-orbit manufacturing. (See ‘Pushing the Envelope')

Mars rover and science

Airbus DS is also a powerhouse for space science missions and Europe’s centre of excellence for the ExoMars Rover. Its Stevenage facility is home to the ‘Mars Yard’ – a testing ground for missions to the Red Planet. Opened in 2014, this facility of Martian terrain has already seen the ESA Mars Rover, ‘Rosalind Franklin’ put through its paces, ahead of a launch in September 2022. On arriving at Mars in 2023 the UK-built Rosalind Franklin will arguably be the most advanced rover on Mars, using artificial intelligence to drive itself around, rather than be directly steered by time-delay from Earth. This will vastly increase the distance travelled and amount of science that it is able to collect.

[THE ESA MARS SAMPLE FETCH ROVER] – IT’S STEM ON STEROIDS

Sarah Macken Director of Business Development Airbus Defence and Space

Beyond that, the UK is playing a key role in perhaps the most exciting Mars mission yet – sample return – an ESA mission to recover the first soil from Mars set to touch down in 2028. This will see a UK-built Sample Fetch Rover perform a critical part in the return of Martian soil to Earth. Material from NASA’s Perseverance Rover will be picked up by the Fetch rover, before being launched off the surface of Mars by an ascent vehicle. Once in orbit, the sample will dock with another orbiter, before firing its engines to return to Earth. This complex and ambitious mission is set to be an historic landmark mission in ESA/NASA co-operation and one in which the UK is set to play a critical role. “It’s STEM on steroids,” enthuses Macken.

Other landmark science missions built in the UK by Airbus include ESA’s Solar Orbiter, the Aeolus weather satellite and the BIOMASS satellite – set to launch in 2022 which will provide vital data on the world’s forests.

Time for a ‘space Team Tempest’?

However, despite its breadth, experience and expertise across the whole of the UK space industrial landscape, Airbus still sees room for improvement – especially in building up and stimulating the UK space supply chain with small and medium-sized businesses. Says Macken: “The UK should really be thinking, how do we develop our supply chain? Why are we sourcing a lot of supply chain material from other countries? How do we bring some of that work to the UK? I think that should be quite a clear strategic target for the UK.”

To that end, in 2020 AirbusDS, in partnership with KBR, Leidos, Northrop Grumman and QinetiQ, launched ‘Open Innovation – Space’ initiative to increase SME involvement in UK future satellite and space activities. Macken notes that the UK space sector needs to reach out to those innovative companies that may be in adjacent sectors but have perhaps not considered the space sector before. “We need to be attracting new companies into space. It can be a low volume of work, so it can be quite a big investment for companies to get into the sector. So we have to attract them.”

An artist’s impression of the Project Oberon spy sat constellation. Oberon would provide SAR radar imagery and ELINT intelligence. Airbus Defence and Space

An artist’s impression of the Project Oberon spy sat constellation. Oberon would provide SAR radar imagery and ELINT intelligence. Airbus Defence and Space

Furthermore, says Macken, compared to other space nations that have both ‘national’ and ‘international’ science missions, the UK currently lacks its own ‘national’ missions. For companies wishing to relocate or open new facilities, having two sources of space missions to tap into, is thus attractive and something that the UK currently lacks.

What is needed, suggests Macken, is some sort of national UK space mission that could pull and stimulate the sector, attract new companies and provide a focus for UK industry and science – a sort of space ‘Team Tempest’ project if you will. Macken, warming to her theme, notes that, if the FCAS/ Tempest is used as a model, there is already a doubly appropriate name for any mission – Prospero – a nod to Shakespeare’s The Tempest and the UK’s Prospero satellite, launched by the Black Arrow rocket from Woomera, Australia.

What form then, could a ‘Prospero 2’ mission take? Macken suggests that, with the UK’s expertise in Mars Rovers (along with SSTL’s and Goonhilly’s Lunar Pathfinder commercial communications mission) there could be scope for a British Lunar Rover mission. This niche could also support US Artemis and wider international Lunar Gateway – as humans return to the Moon for sustained periods.

Left: Rosalind Franklin ExoMars rover in the Cleanroom, Stevenage, UK. Airbus Defence and Space.

Right: Testing of the Fetch Rover at Stevenage’s Mars Yard – the first mission aiming to bring back samples from Mars. Airbus Defence and Space.

Left: Rosalind Franklin ExoMars rover in the Cleanroom, Stevenage, UK. Airbus Defence and Space.

Right: Testing of the Fetch Rover at Stevenage’s Mars Yard – the first mission aiming to bring back samples from Mars. Airbus Defence and Space.

Summary

Despite the uncertainty caused by Brexit and the high-profile UK exits from Galileo, AirbusDS continues to be the bedrock of a thriving and fast-growing UK space sector – that politicians are now looking to help deliver a wider prosperity agenda.

Its deep roots in both military, commercial and science space missions and its breadth of capabilities gives Airbus DS a significant advantage in reusing and spinning off technology from the military sector to the civil sector and vice versa. This ‘virtuous circle’ can also apply to personnel, scientists and engineers, who can bring their expertise, skills and knowledge from seemingly impossible challenges like a Mars Rover to challenges closer to Earth, such as developing ‘bodyguard satellites’ to protect future Skynet military satellites. Says Macken: “Our science missions and why that’s so important to us is that it really stretches the minds of our engineers.”

Its mix of defence, commercial and science business also helps AirbusDS in crucially retaining its expertise and knowledge. Like the UK combat air sector, that has seen the gaps between large programmes widen, with the resultant risk of lost skills a steady and regular stream of business is essential for space businesses to thrive and prosper.

The company is thus highly optimistic about the UK’s potential as an emerging space power, both in military aspects (sovereign ISR, Skynet EC) and commercial (OneWeb) and science missions.

An artist’s impression of an Airbus Skynet 6A

satellite. Airbus

An artist’s impression of an Airbus Skynet 6A

satellite. Airbus Solar Orbiter – built

by Airbus. Airbus

Solar Orbiter – built

by Airbus. Airbus