SPACEFLIGHT UK space industry footprint

The new UK space industrial base

Professor KEITH HAYWARD FRAeS profiles the industrial capabilities of the UK’s wide-ranging space sector, from data services to building satellites.

Cornwall’s Goonhilly ground station is aiming to tap into a growing market for private companies wanting deep-space communication services. Goonhilly

Cornwall’s Goonhilly ground station is aiming to tap into a growing market for private companies wanting deep-space communication services. Goonhilly

For years, UK space was the poor cousin of the much larger ‘aerospace’ sector. It had some superb products, especially in satellite development and construction, and Britain was the host of some important ‘downstream’ players in satellite operation but UK space employment and turnover was a fraction of the overall UK aerospace business. Times have changed. In less than a decade, the space sector has been targeted by successive governments for pump priming with public money, some wellchosen technological investments and a relaunched National Space Agency tasked with implementing a space strategy looking to increase the UK’s share of the global space market to 10% by 2030. To back up these ambitions, the UK government has sunk over half a billion pounds in space over the last decade. It has also passed the Space Industry Act of 2018 to facilitate the growth of launch services – regulating ‘all spaceflight activities carried out from the UK’.

According to ADS data, UK space sector turnover has grown to almost £15bn a year and 40% of all small satellites currently in orbit are built in the UK. The sector has grown overall by 72% since 2012. In 2018, the UK space industry employed just over 42,000 people and contributed £5.7bn (gross value-added) directly to the national economic output, and another £13bn indirectly. Over a third of industrial output was exported. UK space was also highly focused on the commercial sector, with 82% of sales to consumers and businesses. Although UKbased suppliers have lost access to some EU space markets following Brexit – notably Galileo – ESA and some EU Copernicus contracts are still open.

New space

The new UK space sector has moved on from its conventional satellite business to embrace the advent of ‘New Space’, a buccaneering, innovative approach to space hardware and space-based applications. There is even a strong hint that the UK might be back in the launcher business, last seen in the early 1970s; there are certainly plans for UK-located launch sites. All of these novel trends underline the disruptive nature of New Space, turning many of the assumptions of the space economy on its head.

The UK Space Agency is one of many from around the world. ISECG

The UK Space Agency is one of many from around the world. ISECG

In some respects, there are parallels with the impact of UAV technologies on the aerospace sector encouraging the entry of a new set of firms to the aerospace supply chain. The key difference is that, in both cases, the real money is not made by the makers but by the users. As a rule of thumb, building rockets and supplying launch services is the smallest chunk of the space value chain. Satellite manufacturers are better placed and satellite operators (of the big telecommunication birds) have an even bigger share. However, the purveyors of space-based services make the big bucks – think Sky Broadcasting rather than the Astra satellites that beam the signals.

The advent of New Space has changed some of the relative economics of the space value chain. SpaceX launchers and services have lower costs and thus higher potential margins than conventional combinations, such as Ariane/Arianespace. The value of the large geostationary comsats is under challenge from lower Earth orbiting (LEO) constellations and SmallSats generally have brought an entirely new business segment. However, the common theme is that there are even more opportunities to set up space-based services. As ever with tech start-ups – and the space-based service sector increasingly resembles the tech industry in terms of risk/reward calculations – the trick is to sort the valuable wheat from the chaff.

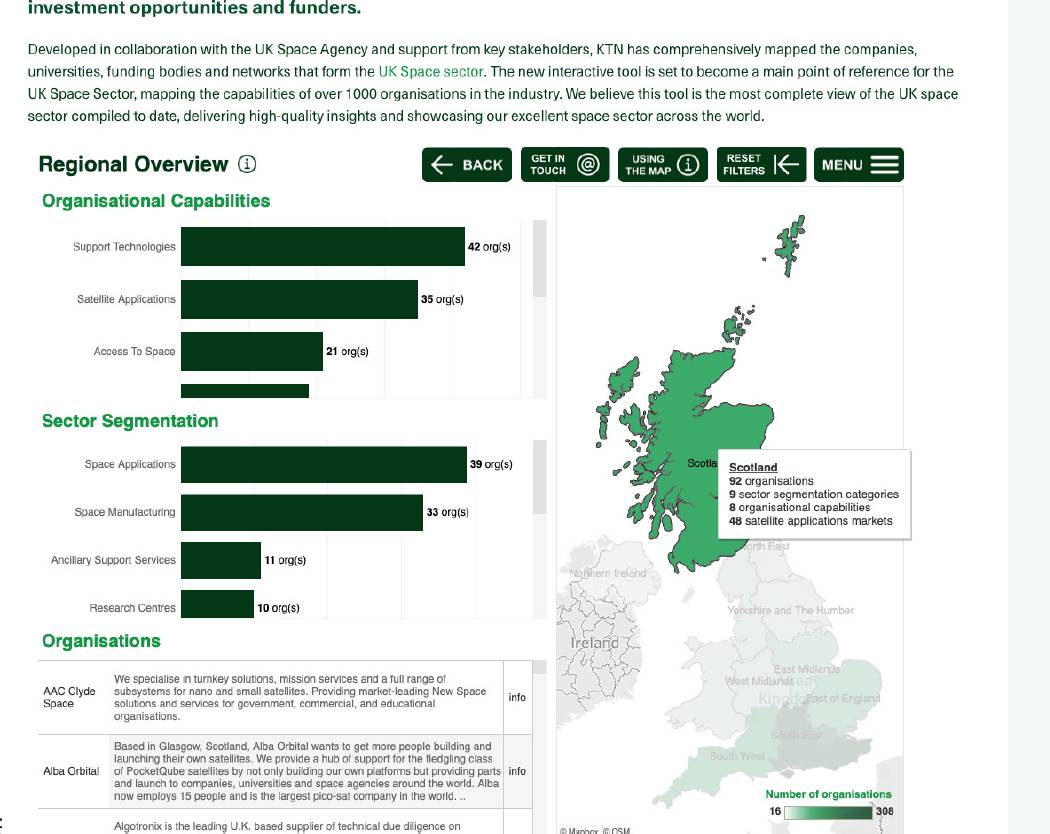

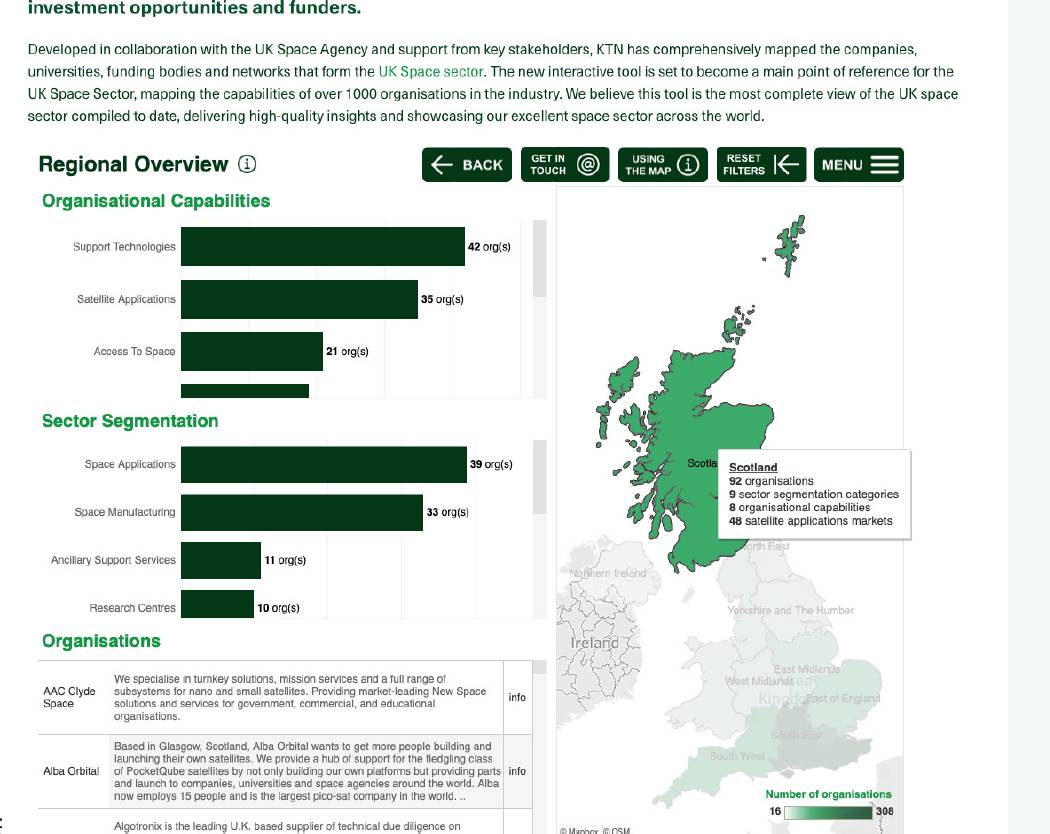

This article focuses primarily on the manufacturing side of the space business, with some glimpses of space-based services. Much of the macro data tends to wrap manufacturing with services – especially if the intent is to boost a political case for investment. However, the KTN-UK Space Agency Landscape Map provides a good way of sorting some of the space sheep from the goats, providing a snapshot of the UK New Space industry.

The geography of UK space

The geography of the UK New Space manufacturing industry is beginning to change away from the traditional clusters around the old core companies, such as Airbus Space and Defence, BAE Systems, Lockheed Martin and Leonardo. While there is still a strong concentration in the South and South East, the map shows a much wider distribution of firms, with a noticeable new grouping in the Central Belt of Scotland – part of the ‘Silicon Glen’ technology cluster. ‘Old Space’ had a more truncated supply chain than ‘aero’, as considerably more of the average satellite comprised ‘one-off’ equipment and subsystems designed and built by the systems integrator. New Space satellite constructors tend to use more bought-in components but these tend to be ‘off-the-shelf’ with less specialised input. Those building the new satellite constellations are also closer to volume production than the traditional players with custom-built products, albeit perhaps based on a standard framework design.

The KTN-UK Space Agency Landscape Map. KTN

The KTN-UK Space Agency Landscape Map. KTN

Geographically, the South East dominates the map of UK space, with 277 players; the next up is the South West with 96 and, third in England, the East with 81. Over half of the total is below the Wash-Bristol Channel line, which is where the great majority of the biggest players in manufacturing or applications are located. This macro-region has 56% of the total space manufacturing sector in the UK and just under half of those involved in applications. Its Eastern component has the bulk of the space industry systems integrators and big applications players. Scotland registers 87 companies in a balanced spread of manufacturing and applications, including a number of spaceport contenders. The traditional aerospace powerhouse of the North West is in eighth place UK-wide, with 38 entities, mainly SMEs.

Manufacturing

The KTN map shows a total of 347 companies and other entities (research groups) engaged in space manufacturing out of 900 mapped as part of the UK space sector generally: 173 are materials and component suppliers; 96 developing satellites, payloads and sub systems; 70 are engineering and scientific support; and 23 are in scientific instruments.

In terms of size, 89 companies have fewer than 10 employees, 93 between 10-50, 47 up to 250 and 74 companies employ more than 250. Most of the latter are mainly well-established aerospace and manufacturing companies. Over half would be defined as SMEs (up to 50 employees) and a fifth of the total have been in business for less than five years.

The big aerospace players, such as BAE Systems, Textron, Ultra, Thales Alenia, Raytheon, Cobham, Airbus Defence and Space (SSTL is listed separately) and Leonardo, are there – along with four university-based enterprises. The bulk of the companies are in satellite or related activities, reflecting the UK’s well-established focus on space vehicles and payloads. Some are in the more exotic contenders, such as the Asteroids Mining Corp and Blue Asteroid, exploring the outer reaches of New Space. The list also includes Garmin, the navigation receiver manufacturer. The ‘space’ sector also includes general high quality/high value component and materials companies, such as Chemring, Constellium (specialist aluminium) and Graphic Plc (printed circuit boards).

Interestingly, given that the UK has had little interest (officially) since the early 1970s in rockets, 29 are involved in launch vehicles and subsystems (See ‘Launching Britain into space’, p34). while some might be supplying into Ariane. Others are part of a wider revival of UK interest in this segment. Many are again parts of the New Space world, looking to develop micro launchers but this group includes Reaction Engines, which continues to work on a potentially revolutionary hybrid engine, along with the historically redolent Black Arrow, a SmallSat launcher specialist. Virgin Galactic (and Virgin Orbit) is perhaps the most well known member of this group. As all but six have fewer than 20 employees, this is again perhaps evidence of the flourishing ‘start-up’ characteristics of the UK New Space sector.

The Shetland launch site at Lamba Ness on the island of Unst, as imagined. Lockheed Martin

The Shetland launch site at Lamba Ness on the island of Unst, as imagined. Lockheed Martin

Space applications

The space applications sector lists 308 companies. The main areas of activity are Earth observation and telecommunications. There are 108 companies with fewer than 10 employees, 97 with between 10 and 49, 25 in the 50-249 category and 87 with more than 250. Over 65% of space applications firms are in the SME category. The big players are again well established: Airbus Space and Defence communications, BT, Eutelsat, Inmarsat and Telespazio, as well as the large direct broadcasters, such as Sky and Freeview. In the case of many of the larger companies, the space aspects of their activities may be relatively small but vital: the Sky annual report has little direct reference to its satellite network but has pages of small print mitigation for loss of access.

Inmarsat is perhaps the doyen of UK-located space applications business. Established in 1979 as a non-profit intergovernmental organisation to operate mobile satellite communications for international shipping and later aviation, in 1999 it was privatised and since then has established several partnerships to extend its services. Inmarsat operates 14 GSO satellites from its London base. A key feature is the global maritime distress and safety service. As well as the maritime sector, Inmarsat works across government, enterprise and aviation sectors worldwide, including in-flight internet connections for the European Aviation Network.

Nearly a third of companies in this sector are less than five years old, a rather higher proportion than in manufacturing, which would seem to reflect the relative ease and attractiveness of setting up in the downstream arena. A number have been around a lot longer then that. Paddle Logger, a water enthusiast tracking service, has been in business for over five years and Remote Sensing Applications has been using space-based data since 1986. PlanetWatchers, a classic SME which has been operating since 2019, is typical of the new entrants, using space-based data to track and assess storm damage. Similarly, Orbital Witness has been deploying data from satellites in real estate legal cases since 2017.

Some of these UK-based companies are a part of a multinational business. A good example is Spire, the US Earth observation company, operating a constellation of 90 CubeSats offering a range of data analytic services. Its weather forecasting service is in Glasgow. Spire cites good access to capital and technical resources as the reason for choosing Scotland.

Thales Belfast is now a centre for satellite electric propulsion modules. Thales UK

Thales Belfast is now a centre for satellite electric propulsion modules. Thales UK

Ancillary support services

This sector lists 192 companies, mainly consultancies of one form or another. There are 79 companies with fewer than 10 employees, 34 in the 10-49 category, and 13 between 50 and 249, with 50 big players. The sector has some important commercial actors, including Lloyds, Allianz, Aon, Bird and Bird and Marsh, offering insurance, legal services and general support for the space sector. In general, this is the arena for SME operations: over half have fewer than 50 employees.

Space operations

There are 33 companies in this sector, again companies like Airbus, Avanti, Telespatizio, Serco and QinetiQ (mentioned in all the major categories), but 119 (57%) are SMEs. Fourteen are newly established, or 42% of the total.

NEARLY A THIRD OF COMPANIES IN THIS SECTOR ARE LESS THAN FIVE YEARS OLD. A RATHER HIGHER PROPORTION THAN IN MANUFACTURING, WHICH WOULD SEEM TO REFLECT THE RELATIVE EASE AND ATTRACTIVENESS OF SETTING UP IN THE DOWNSTREAM ARENA

The OneWeb LEO broadband communications megaconstellation is perhaps the most interesting member of this group. This is a highly controversial public-private investment tipped (at least in the original publicity) as potentially a British alternative to Galileo. The Satellite Applications Catapult, a government-funded innovation hub, is already working with OneWeb to develop add-on positioning, navigation and timing technology that could be used to enhance the resilience of existing navigation services, such as GPS. However, the OneWeb satellites are built by Airbus in the US and any returns will be entirely dependent on selling its services.

The OneWeb LEO constellation was bought out of bankruptcy by a consortium of investors led by the Indian Bharti Global. The UK has invested $500m in a 45% share of the relaunched company but officials refused to sign off on the deal. Its value as a geo-location system is still uncertain but the UK government also believes that OneWeb will fill an important gap in internet access for remote centres. OneWeb will be in competition with megaconstellations funded by Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos.

Spaceports

Encouraged by the UK Space Agency LaunchUK initiative aimed at providing an appropriate regulatory framework, seven sites in the UK – including Newquay in Cornwall, Campbeltown, the Hebrides, Sutherland and Glasgow Prestwick in Scotland, the Shetlands and Snowdonia in Wales – have announced spaceport plans. Four of the seven are located in Scotland. Three are offering vertical and three or four of the sites horizontal launches. The commercial exploitation of these centres has been boosted by agreement with the US authorising export-controlled technologies on American satellites which can be launched from British sites.

Spire Global nanosatellites cleanroom at its Glasgow facility. The company is set to expand further, having signed a 10 year lease in February 2021 to move to a larger 29,511ft2 facility in the city’s Skypark. Quentin Gollier

Spire Global nanosatellites cleanroom at its Glasgow facility. The company is set to expand further, having signed a 10 year lease in February 2021 to move to a larger 29,511ft2 facility in the city’s Skypark. Quentin Gollier

The UK government has also agreed to fund facilities to support Virgin Orbit operations. The UK sites will be used to launch SmallSats and perhaps as centres for space tourism, the former aimed at polar orbits, taking advantage of northern latitude launch of Earth resources satellites. Lamba Ness in the Shetlands was first off the mark; the Shetland centre believes that it will generate over 600 jobs directly and indirectly across Scotland. Some £50m of public money has already been invested in the Shetland site, with Lockheed Martin getting £23.5m to support launch activities. Lockheed transferred its business from the Sutherland Space Hub because Shetland offered a more direct launch trajectory. This was followed by Newquay’s horizontal launch site, ‘Spaceport Cornwall’, with a £7.5m state boost afforded to Virgin Orbit.

Lockheed Martin has contracted the start-up ABL Space Systems to supply a rocket and launch service for operations based in the UK. Its Pathfinder Launch programme is due to launch the first vertical small satellite from the United Kingdom in 2022. The American ABL Space Systems is developing the RS1 small satellite launch vehicle. Lockheed Martin has been a strategic investor in the venture since 2019. Other companies, such as Orbex and Skyrora, both headquartered in Scotland, are also in the small launcher market. Orbex is still the only company with posted commercial contracts for a British launch, in this case from Sutherland. Virgin One’s recent successful test is encouraging news for the Cornish horizontal launch site.

Analysts have been quick to point out that, worldwide, there is already considerable competition for the SmallSat launch business – and as a relatively modest element of the space industry value chain, UK launch sites may struggle to make money. The British government contends that the commercial demand for commercial launch services is potentially worth £3.8bn to the UK over the next ten years. This seems somewhat optimistic.

The likelihood that all of these space centres will be profitable is low: and even if modestly so, the wider exploitation of these remote locations (with the exception perhaps of Prestwick), in the form of manufacturing or space services clusters, is doubtful. There may be some utility in having some degree of indigenous launch capability but the major constellation operators are likely to use sites closer to home or an established and proven launch service; even the partly UK-owned OneWeb is looking elsewhere (so far mainly Russian rockets and sites) to launch its satellite network. In this respect, the Lockheed-supported operation seems to be the most likely to make a commercial breakthrough.

And the next steps?

The UK space industry has grown rapidly over the last few years. This has followed an impressive increase in public funding and active promotion by a revitalised National Space Agency. It has fully embraced the principles and the challenges of New Space. The space applications sector has been especially active in terms of both depth and scope of interests.

In addition to the largely commercial activity described above, the UK is embarking on a more active role in military space. This effort will be boosted by £1.5bn in the latest UK Integrated Review. However, the MoD may want to stretch its funds through co-operation with the private sector, exploiting the ‘dual technology’ features of many space applications. This could include buying launches, bypassing the emerging SpaceX dominance of the commercial business – if the price and capability is right!

Another interesting trend to watch at the top end of the industry is the emergence of teams bidding for ‘end-to-end’ contracts. The recently formed Athena, a team comprising Inmarsat, Serco, CGI UK and Lockheed Martin, offers an interesting mix of space goods and services. By exploiting its components’ individual strengths, it could deliver a comprehensive range of civil and military applications, offering a ‘sovereign UK-based’ service for the MoD. Athena wants to encourage a wider range of smaller companies supplying into the ‘team’. This approach should have the effect of further encouraging the UK New Space industrial base and providing some insurance against technical and commercial risks associated with the more speculative space markets.

Meanwhile, an Airbus Defence and Space consortium, including QinetiQ, Northrop Grumman, KBR and Leidos UK, which was announced last December, is looking to provide a range of spacebased assets and services. It also aims to place 30% of the work in the UK space SME community. The group accounts already for £5.8bn worth of UK space business. Its primary target will be MoD’s secure communications market.

All of this activity, new and old, is a long way from the UK space backwater of the 1980s, and in many respects, it puts the British space industrial base in the forefront of the new space markets of the 21st Century. Whether the UK will attain the goal of doubling its market share by 2030 remains to be seen but even a near miss will be well worth the effort.

Cornwall’s Goonhilly ground station is aiming to tap into a growing market for private companies wanting deep-space communication services. Goonhilly

Cornwall’s Goonhilly ground station is aiming to tap into a growing market for private companies wanting deep-space communication services. Goonhilly The UK Space Agency is one of many from around the world. ISECG

The UK Space Agency is one of many from around the world. ISECG