PLANE SPEAKING HE Sarah Al Amiri

Plane Speaking with: HE Sarah Al Amiri

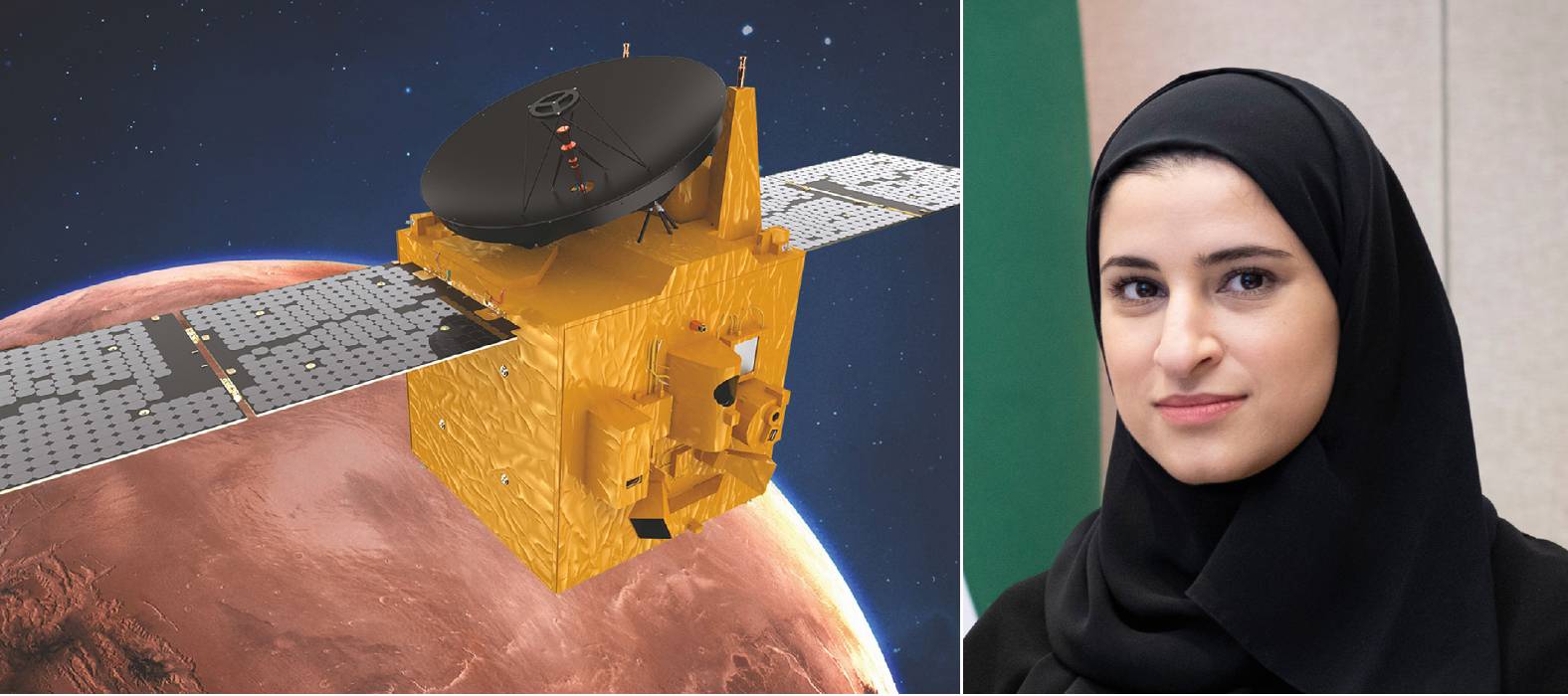

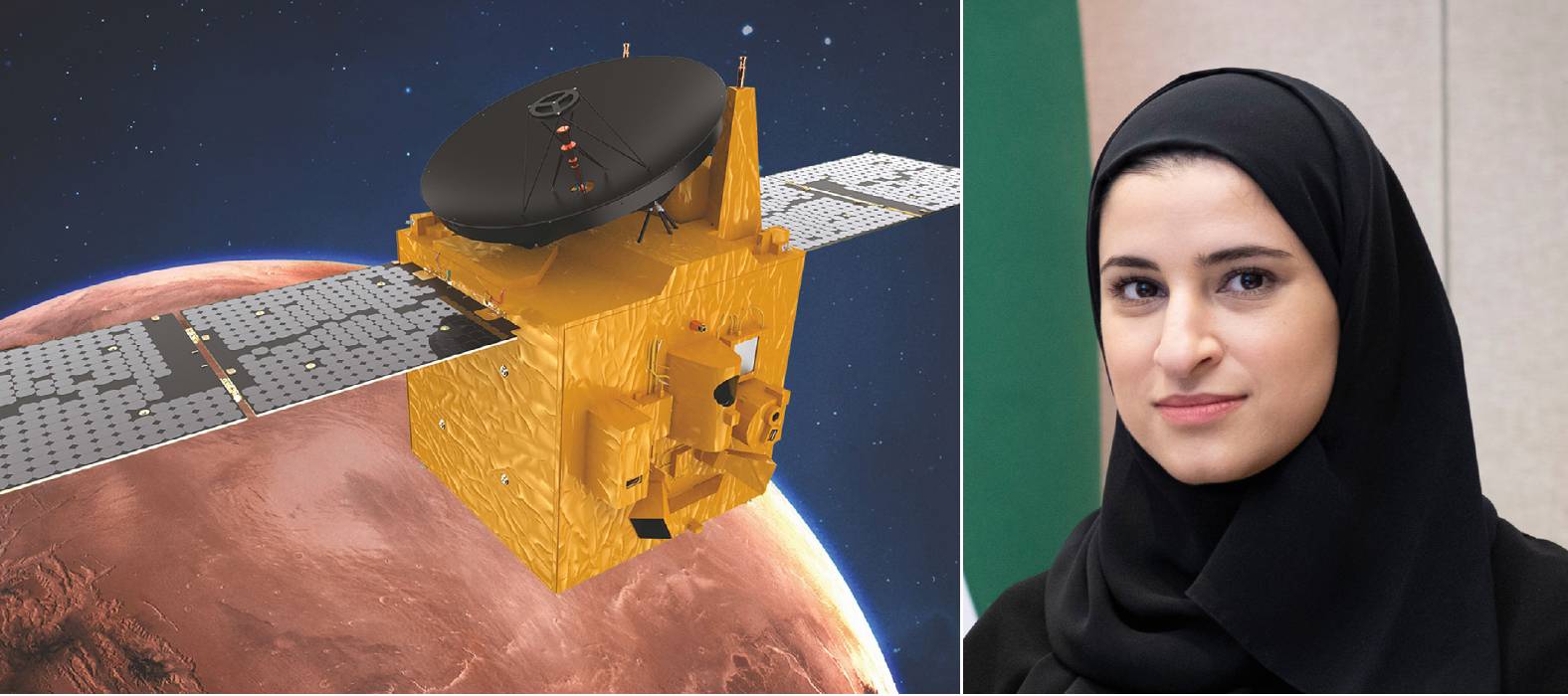

Earlier this year, the United Arab Emirates became only the fifth nation and the first Arab country to reach Mars with its Al-Amal (Hope) space probe. AEROSPACE caught up with HER EXCELLENCY SARAH AL AMIRI, Chair of the UAE Space Agency and Deputy Project Manager of the Emirates Mars Mission to ask her about this historic achievement and the UAE’s ambitions in space.

MBRSC; UAE Space Agency

MBRSC; UAE Space Agency

AEROSPACE: Can you summarise the United Arab Emirates’ space strategy? Why did the UAE decide to get into space in the first place?

HE Sarah Al Amiri: One of the primary objectives was developing the science and technology ecosystem within the country, developing capabilities and, more importantly, capacity. However, most critically, was the diversification of our economy. We need to ensure that we have sectors of the economy that are not dependent on traditional industries like oil and gas but instead develop those that focus on technology and enhancing knowledge capabilities and therefore space became an obvious choice.

Through developing our space programme, it enhances our capabilities across several areas of expertise within technology, making it easier to transfer the experience and build a team around that. Now, as we slowly move towards transferring this to economic impact and industrial development, especially with the space sector, we are looking at the further development of new companies within the space sector. With this in mind, a significant part of our overall strategy is ensuring our ecosystem is robust and allows for these companies to flourish. In addition, we still have programmes and projects that continue to develop capability and capacity in the sector and create business for the private sector.

AEROSPACE: Can you give us an idea of the UAE Space Agency’s resources? How many people does it have?

SAA: We have a team of 60 people at the space agency. It’s not a large organisation, and it will remain a relatively small one. Development happens at other government agencies and projects happen at other government institutions. We are solely responsible in ensuring that we also have a private sector that is aligned with that and the establishment of university-based research institutions to ensure that we bridge the full spectrum from research all the way to implementation.

Our focus area over the course of the next year is demand creation. In practical terms this means socialising with various other sectors and other stakeholders on the outcomes and utilisation of the space sector and how it feeds into other sectors. That’s ultimately how you drive demand in the space sector. It is also the regulator of the space sector in the UAE, helping to provide the overarching strategies for the sector, determines the projects that are funded and provides oversight of the projects and programme management. We have a bird’s-eye view of the technologies that need to be developed within the space ecosystem in the Emirates and ensure that there are institutions that are adopting development practices that can help achieve this.

AEROSPACE: How do you see the international space landscape in terms of co-operation or competition with other agencies and partners?

IT WAS ALWAYS GOING TO BE MARS. WE ALWAYS KNEW IT WAS GOING TO BE DIFFICULT BUT NOW, IN RETROSPECT, THIS DIFFICULTY ALLOWED US TO DEVELOP AS A TEAM FASTER THAN WE WOULD HAVE IF WE TOOK A STEPPED APPROACH

SAA: For as long as I have been in the space sector, it has all been about co-operation. Yes, competition exists but I think it is a healthy form of competition across the spectrum and we continue to be an international player in the space sector. We’ll continue to leverage international partnerships to further enhance our position. You cannot develop a space sector that’s completely siloed away.

We’re interdependent, even when you go down to the component level. Nobody develops a spacecraft, the utilisation of byproducts, or even a scientific mission completely on their own. They tap into various ecosystems. So, international collaboration is vital. From the perspective of the UAE Space Agency, the way we’re looking at it, is that international co-operation is actually an enabler of your space sector and not an offset aspect that just becomes a box-ticking exercise in international relations.

AEROSPACE: The UAE’s Mars Hope has been big news this year. Why was Mars chosen as the goal for Hope in the first place? Were there other mission options you looked at that were discarded?

SAA: No, it was always going to be Mars. We always knew it was going to be difficult but now, in retrospect, this difficulty allowed us to develop as a team faster than we would have if we took a stepped approach. It did something that’s very important for anyone that wants to transition into having more technology-based industries within their economy and that’s increase the risk appetite and the acknowledgment that failure is part of the process towards success.

That is something that’s quite drastic that we learned from the Emirates Mars mission. Even going from Earth observation, when you’re talking about 95% success to jump all the way to a mission to Mars, where all the factors are not in your control, allowed us to expand our capabilities to things that we could have never done before, even in other sectors. So, in summary, it’s about increasing the appetite for risk, rapid development of capabilities and then finally, developing the mindset that – especially when you’re talking about experimenting with technology – failure is on the path towards success. Those are valuable lessons that we’ve learned over the course of the past seven years.

AEROSPACE: The Hope Mars probe was built in the US in partnership with a US university. Is the ambition to build the next spacecraft in the UAE?

SAA: Well, the way that we approached this and the reason we were able to fall into our cost envelope and be relatively lower cost, was to look at only developing infrastructure that is absolutely necessary, while leveraging international partnerships and taking advantage of infrastructure that is already in existence. I don’t believe we will stray away from that model just by the simple fact that you are able to innovate differently when you open up and remove the limitations of where you design and develop.

With this in mind, I wouldn’t commit to saying that we will definitely build the next spacecraft here in the UAE, because it might make sense for any other mission to be built outside the UAE and for us to work on a mission elsewhere, to use facilities across the world, to do parts of it here, parts of it elsewhere. There is absolutely nothing wrong with that. We actually learned more from being embedded in an ecosystem that already existed than we would have ever learned by having subsets of people come into the UAE and develop things here.

Mission control for the Emirates Mars Mission. MBRSC

Mission control for the Emirates Mars Mission. MBRSC

AEROSPACE: You mention that Mars Hope helped increase appetite for risk and innovation – can you expand on that?

SAA: Risk appetite allows you to look into several facets. If I talk about it from an ecosystem perspective, you’re allowing for more capital, more financing and more funding to go into higher-risk projects and develop the necessary programmes to ensure that they can absorb the shocks from failures especially in the financial sector. So that’s one ecosystem-level learning from a higher risk appetite. The second is putting together a system,, where things can go wrong but ensuring that it allows you to recover from whatever goes wrong. This was very much the approach of the Emirates Mars Mission.

Having projects that are funded by the space agencies provides the necessary oversight on how much leeway there is for experimentation to ensure that you’re not failing at the wrong time and you’re not recovering from that failure again at the wrong time. In this sense we were taking on the motto of ‘fail fast and fail forward’ and ‘fail rapidly on the path to success’. These are aspects that are now built into how we deploy programmes for the startup ecosystem.

AEROSPACE: Is Hope being used in educational packages that go into schools and universities?

SAA: It always has been. We’ve actually had an education outreach team established together with all the other teams that were a part of this mission. Outreach was a very intrinsic part of all of our jobs on the team. We’ve had programmes reaching tens of thousands of students, probably into the hundreds of thousands. We had it at the level of teachers and had it at the level of students. We went from preschools all the way to postgraduate education, and we have different packages that fit into it. The Mars mission also features in our national curriculum. In addition, Covid-19 introduced us to the world of online webinars, so we continue to leverage on those for education purposes.

AEROSPACE: The UAE Space Agency is one of the youngest and most gender-balanced space agencies in the world. What’s the secret to attracting more women into science and engineering?

SAA: Over the course of the past 20 years, we’ve seen a gradual increase in women entering into STEM to the point where every year you see a form of parity in the number of males versus females in STEM subjects and that is now reflected at organisations at entry-level. Thus, if you’re talking about a change that happened almost 10 to 15 years ago, you’ll see people who have been working ten years and under in nascent organisations, like the space agency and other sectors, and you’ll see a better mix of gender due to that fact. Now, why do we have more students coming into STEM? I still haven’t been able to find the answer to that question but I guess it’s as acceptable in the community for women to be engineers, to be scientists and researchers as it is for men. So, we don’t hear that intrinsic gender bias as we grow up and I think that’s one of the main reasons that it hasn’t percolated across.

On the Emirates Mars mission we’ve had about 34% women which is quite high in comparison, not quite at parity but very high in comparison to other institutions. Our science team is 80% women. It is important to stress that everyone is there on merit. That’s something that I can guarantee. We never had a quota system in place and we never will have a quota system. You just need to ensure that you have the right unbiased organisation in place.

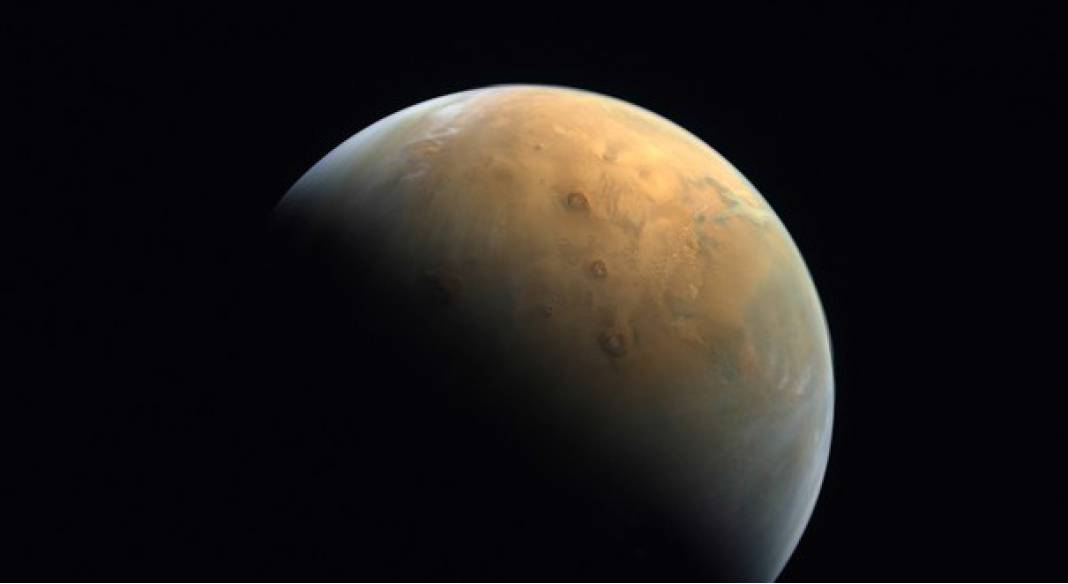

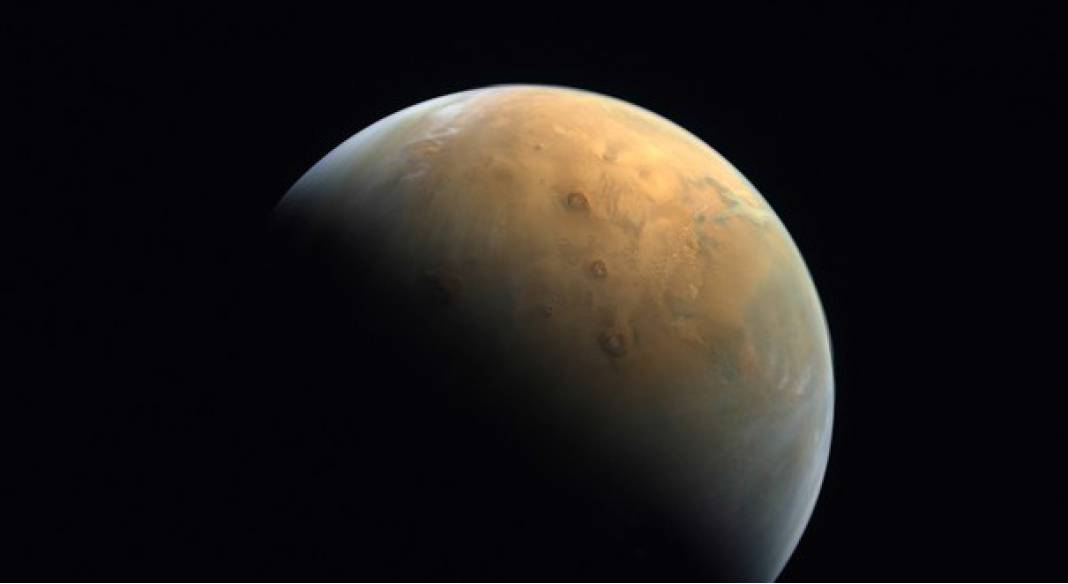

The first image of Mars from Hope was sent back in February. MBRSC

The first image of Mars from Hope was sent back in February. MBRSC

AEROSPACE: In other countries, we see people cross over from the aerospace sector into spaceflight. Is that so in the UAE’s space sector?

SAA: We do this in several ways. We have individuals and we have organisations. So, at the level of individuals, we have people coming from the aircraft industry here in the UAE, especially in the maintenance and MRO aircraft industry, into the space sector but most of the engineers that were hired into the programme were fresh graduates. This is why, through creating partnerships with various countries and various institutions and embedding our team in their team, we were able to build that experience and transfer that necessary know-how.

In fact, I think one of the best Emirati systems engineers that I’ve worked with was our system engineer on the Emirates Mars mission, Mohsen Al Awadhi, who came from an aircraft background and worked in Emirates and then came into the organisation a few years later. On the organisational side, we looked at the materials. It is often the case that the electronics are hard to upgrade to spacegrade standards during the time that we had for the mission development. However, the hardware is relatively easy, especially the metallic frames and the structures.

What we did is that we worked with a few manufacturers to look at their current processes for manufacturing and started developing parts. We do have mechanical parts, even some of them belonging to our instrumentation currently in orbit around Mars developed by Tawazun Precision Instruments, based out of Abu Dhabi. They also manufacture aircraft parts and now one of their instruments is on a spacecraft around Mars and that’s not something that we thought was possible. Just by upgrading processes we were able to match space grades and pass testing for it to be in orbit around Mars. This highlights the success of a methodology which we were able to cross between sectors with a few tweaks.

The Hope Mars probe in a clean room prior to launch. MBRSC

The Hope Mars probe in a clean room prior to launch. MBRSC

AEROSPACE: In attracting foreign partners, space companies, investors, what would you say the UAE’s niche is in space?

SAA: The software is definitely something to leverage, especially if we’re talking about data analytics for Earth observations. The second one is tapping into the market of Earth observation satellites about 200kg and lower, something that sits between 100-200kg. But the aspect that we are now focusing on is the rapid development of spacecraft and streamlining the development process to be able to use it across different applications.

One of the primary drivers that then goes into it is ensuring that we have shared infrastructure utilisation. This would mean the overheads for companies to start up here in the UAE would become less and less. That is about ensuring that you have shared space for ground stations for communication, utilisation of processing power on existing cloud servers and ensuring that they have the necessary tools in place. These are all aspects that we’re currently looking at today. Another factor is ensuring access to clean rooms and testing facilities, be it within the country or even outside and building that network. That then brings companies in, without the need to think about infrastructure, because they already have access to it. The same goes with training of personnel for assembly integration and testing. We’re trying to alleviate a lot of overhead costs that go into space sector organisations.

AEROSPACE: Can you see the UAE acquiring or developing its own launch capability to access space?

SAA: Not at the moment because, if you look at the market trends for first space launch, they’re becoming lower and lower cost each time and we’re leveraging that. So it’s not something that’s being discussed at the moment. But we are interested in looking into topics such as space debris and de-orbiting capabilities, for example. This is a scenario that we need to be looking at, especially with the advent of smaller and smaller satellites in space. How do we ensure that we’re able to do that and then even looking at built-in capabilities in spacecraft without increasing costs for de-orbiting? These are the sort of aspects that we are looking at that are not necessarily of importance today but are things that you would need to look at five to ten years from now.

MBRSC; UAE Space Agency

MBRSC; UAE Space Agency