ROTORCRAFT EMS and Covid-19

Helicopters rise to the challenge of Covid-19

BILL READ FRAeS reports on an RAeS webinar which looked at how manufacturers and operators of military, civil and aeromedical helicopters are responding to the new challenges posed by the Covid-19 outbreak and how their aircraft are being adapted to assist with medical evacuations.

On 12 May, the RAeS held an online webinar ‘Covid 19 – Helicopter transport – challenges & experience’ in which representatives from the armed forces, national coastguards, offshore transport operators and manufacturers shared their experiences of how they have adapted their helicopters and methods of operating to provide assistance with emergency medical evacuation flights.

In response to the Covid-19 outbreak, military, civil utility and aeromedical helicopters have been pressed into service to assist with the transport of patients. The rapid development of the pandemic has allowed little time for ‘best practice’ to be developed and manufacturers and military and civil operators have had to devise solutions to react to the ever-changing situation.

A CH-47 Chinook

helicopter, assigned to the

New York Army National

Guard makes a delivery

at a helipad in New York

City, April 2020. New York

National Guard members

are supporting the

multi-agency response to

Covid-19. US Air National Guard

A CH-47 Chinook

helicopter, assigned to the

New York Army National

Guard makes a delivery

at a helipad in New York

City, April 2020. New York

National Guard members

are supporting the

multi-agency response to

Covid-19. US Air National Guard

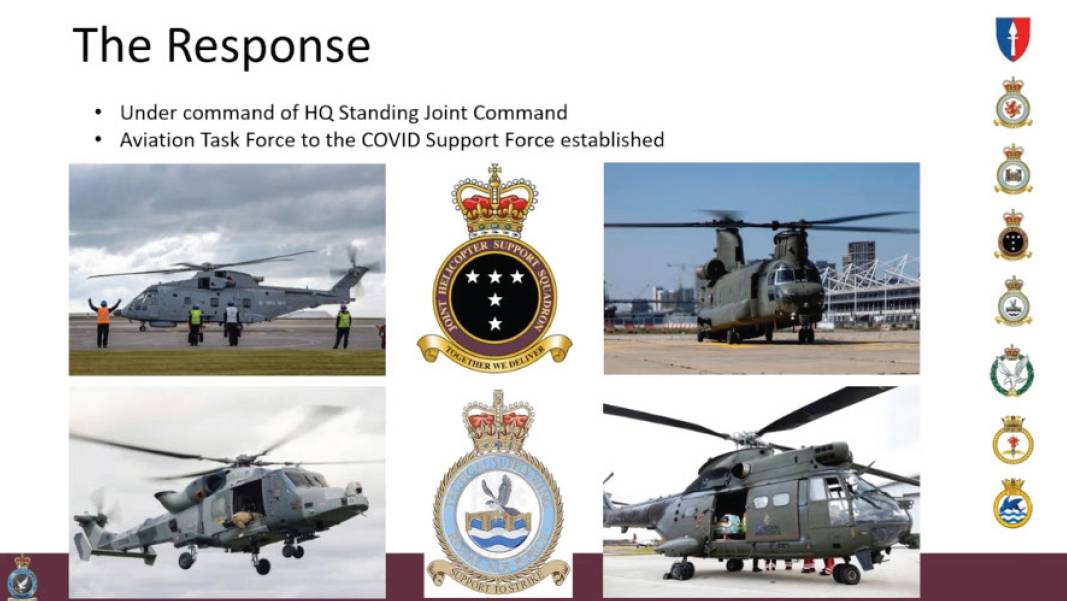

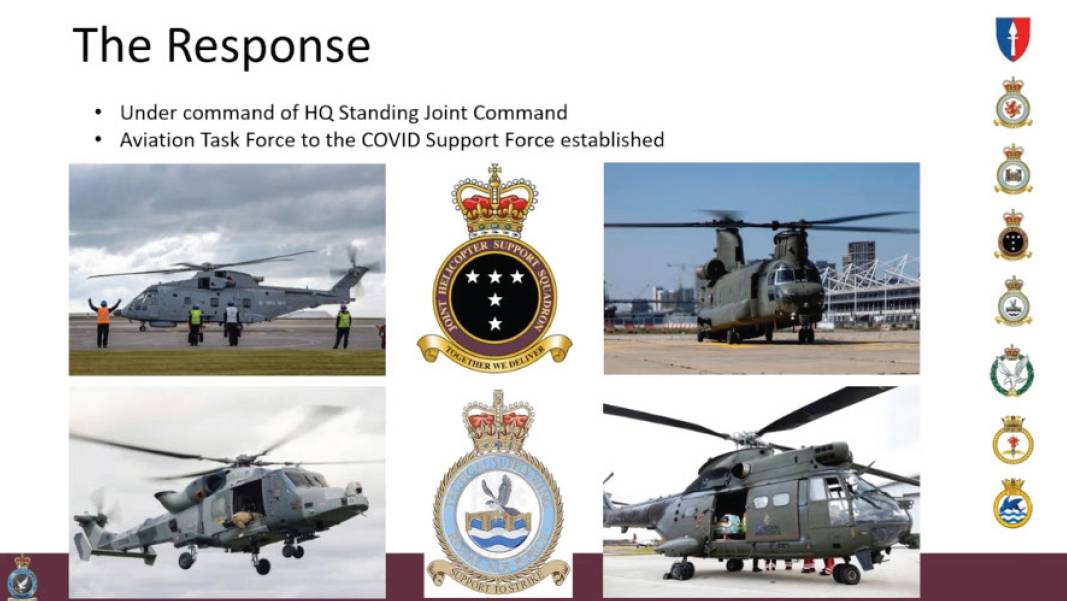

Operation RESCRIPT

Wing Commander Elizabeth Gilbertson MRAeS, Officer Commanding Engineering and Logistics Wing, RAF Benson explained about Operation RESCRIPT which provides military support to the UK civil authorities coping with Covid-19, including the carriage of critically ill patients, medical staff and supplies. The helicopters involved are RAF Pumas and Chinooks, Army Wildcats and Royal Navy Merlins. Wg Cdr Gilbertson explained how the current crisis has required the helicopters to temporarily relocate away from their regular bases to new centres of operation where they can provide a wider coverage.

Safety modifications

It was then the turn of Sam Schaab, Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) Specialist at Leonardo Helicopters to outline how the manufacturer was assisting civil and military helicopter operators to adapt their aircraft to be used for medical evacuation. He explained how patients infected with Covid-19 needed to be transferred in special biocontainment units with a physical separation barrier fitted between medical staff accompanying the patient and the driver of the vehicle.

To carry infected patients, helicopters – even those already configured for medical evacuation (medivac) missions – needed to be modified to have the same safety features adopted in ground vehicles and in fixed-wing aircraft. The most important of these was to fit a separating wall between the air crew and the patient compartment. “We looked at existing cockpit separating devices, as well as identifying third party suppliers who could provide solutions for operators,” explained Schaab. “These include seals for existing curtains, as well as retrofits which could also be supplied as kit in the future. The challenge was to respond quickly. The pace of change has been very rapid, so we’ve got to respond just as fast.”

The UK armed forces have mobilised RAF Pumas and Chinooks, British Army Wildcats and Royal Navy Merlins to support the UK civil authorities response to Covid-19. MoD

The UK armed forces have mobilised RAF Pumas and Chinooks, British Army Wildcats and Royal Navy Merlins to support the UK civil authorities response to Covid-19. MoD

Biocontainment devices

Sam Schaab also explained about biocontainment devices (also known as patient isolation devices (PIDs)) which are human-sized isolation pods designed to prevent infected patients from infecting other people. “Biocontaiment devices bring an additional level of safety but there are logistical and training challenges,” he told the conference. “Bicontainment devices are designed so that they can be secured to existing litters within the aircraft. They provide consistent positive airflow pressure to isolate the patient from the outside with the ability to perform patient care through sealed access ports.”

Two examples of such devices are:

IsoArk N-36 from Beth El Industries – self-contained unit, collapsible, relatively small and portable, less expensive than other systems, blower system with lots of filters, cannot be used for CPR, attaches to existing litter systems or to floor mounts.

EpiShuttle from Epiguard– rigid self-contained unit, more expensive, cannot be collapsed but is a more robust structure. Can be attached to existing litter systems and floor mounts in aircraft. Schaab said the different biocontainment designs needed multiple approvals through different certifying bodies.

Leonardo response

Schaab described how the company had assisted a range of different Leonardo Helicopter operators with modifications and support. In the UK, three AW101 Merlin Mk2 helicopters from 820 Naval Air Squadron based at RNAS Culdrose in Cornwall have been used as air ambulances across South West UK and offshore islands; three AW159 Wildcat helicopters from 1st Regiment Air Air Corps based as RNAS Yeovilton were on call for south of England and then were deployed to other areas.

In Italy there was a quick reaction from the government in providing a co-ordinated military and civil response and transport between hospitals was done by Italian Air Force AW101 equipped with biocontainment equipment. Meanwhile, private operators are starting to use their helicopters fitted with a special insulated stretcher designed for biocontainment air transport. The Italian Health Ministry and Civil Aviation Authority has authorised Babcock to install isolation stretchers, IsoArk N36-2 and N36-4 biocontainment units on AW139 and AW169 helicopters.

The Epishuttle patient isolation device. Epiguard

The Epishuttle patient isolation device. Epiguard

Airbus solutions

Stefan Bestle, Key Segment Manager HEMS, Airbus Helicopters then described the ways that Airbus Helicopters is assisting to find Covid-19-relevant solutions. Airbus has also faced similar problems to Leonardo with fast-tracking the safety certification of cabin modifications and operations.

Airbus also had to find quick solutions to enable cockpit-cabin separation and the carriage of patient isolation devices. “It usually takes time to do modifications but Covid-19 doesn’t wait,” explained Bestle. “For cockpit-cabin separation we found a solution using a non-aeronautical material which was available globally for customers which was suitable for both large and small helicopters.”

From search and rescue to patient evacuation

Examples of different cockpit/passenger compartment separation techniques. Leonardo

Examples of different cockpit/passenger compartment separation techniques. Leonardo

Offshore transport providers and search and rescue (SAR) operators have also been adapting helicopters for Covid-19 patient transport. One company involved in both sectors is the Bristow Group which provides helicopter transportation to the offshore oil and gas industries, as well as SAR services. Capt Clark Broad, Flight Operations Manager from Bristow Helicopter Search and Rescue explained how the sudden escalation of the pandemic in March had affected operations. “When the pandemic began, like the rest of the population, our crews were fearful of the virus and did not want to expose themselves or their families to infection. We had a 17% absence rate away from work due to self-isolation. Crews were not familiar with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidance and processes in the Clinical Governance Document.”

Broad went on to explain how the offshore industry had had an immediate need for helicopters suitable for carrying infected or potentially infected personnel from offshore installations. Because fewer people were going to sea because of travel restrictions, SAR operations fell by 75% and the S-92 helicopters used for search and rescue were lying idle. Using the protocols developed from carrying SAR patients, Bristow was able to convert its helicopters to carry Covid-19 patients while protecting both crew and passengers. “Using the C-Med S-92 concept developed using SAR expertise, we have now transported 120 suspected Covid-19 patients from offshore installations without ill effects to crew,” declared Broad. “We now have cockpit barriers in both AW189 and S-92 helicopters which means that pilots don’t have to wear masks. We can carry the EpiShuttle in both the AW189 and the S-92. We haven’t had any negative effects and our crews are gaining confidence.”

Coast Guard experience

Patient in a protection cover being loaded onto a SAMU Airbus helicopter. Airbus Helicopters

Patient in a protection cover being loaded onto a SAMU Airbus helicopter. Airbus Helicopters

The next speaker was Davitt Ward, Chief Crewman Medical Standards from CHC Helicopters Ireland which provides both SAR and HEM services for Ireland. He gave details of how CHC Helicopters worked with the national ambulance service and accelerated crew infection testing results. “Crews are now wearing masks on all flights but we did have to get everyone who had beards to shave them off,” he admitted.

Ward explained how CHC Helicopter pilots wore ALPHA Eagle 900 helmets with respirator mask and bayonet connectors. Patients had been carried on Priority 1 Air Rescue stretchers while crews had worn Virustatic Shield snoods and safety goggles. “The recommended UVEX goggles got fogged up with anti-fog spray so that we couldn’t read with them, so we used prescription safety goggles instead,” he said.

Icelandic saga

A second coastguard perspective was given by Jón Erlendsson from the Icelandic Coastguard.

He explained how the Coast Guard in Iceland operates using a fleet of three helicopters (two H225s and one AS332L1), and one Dash 8-314 fixed-wing aircraft. Erlendsson described how the Coast Guard had so far had one Covid-19-related mission to the west part of Iceland when bad weather stopped normal aircraft getting there.

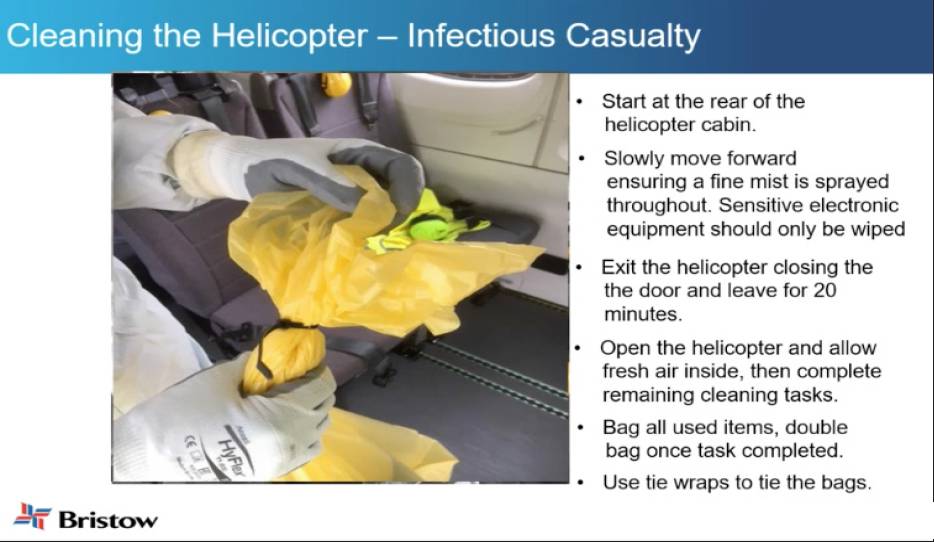

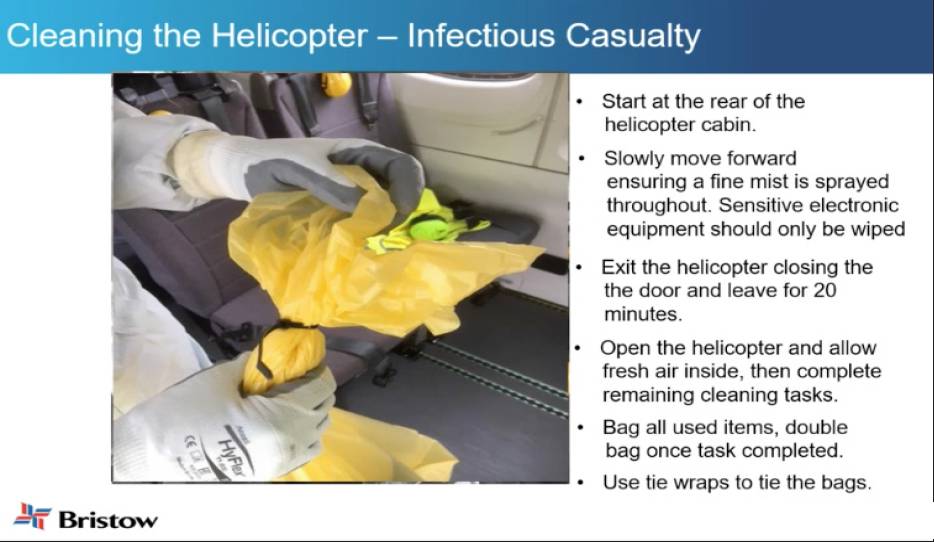

How to clean an aircraft

Until recently, aircraft cleaning and the techniques used was not a topic that was widely discussed. However, with the spread of Covid-19, the decontamination of aircraft interiors has become a hot topic and one that was mentioned by all the webinar speakers. While Covid-19 can spread from infected people to those who are in close proximity (hence the need for masks, screen and patient containment), it can also be transmitted through contact with infected surfaces, thus making the need for decontamination essential.

The sixth speaker at the webinar was Andrew Dutch from 1710 Naval Air Squadron, Corrosion Control HOD who described the process of how to disinfect an aircraft in some detail. There were two ways to disinfect aircraft from Covid-19. One was the passive method in which the aircraft is left alone for three days. The other is the active method in which a product is applied to disinfect aircraft surfaces. Dutch explained how some disinfectant materials are OK to be used on passenger aircraft where the cabin interiors are fitted with soundproofing and panels. However, the same disinfectants are not so good on aircraft with exposed internal structures.

Cleaning options

Looking at the cleaning options in more detail:

Bristow guidelines on how to clean a helicopter. Bristow

Bristow guidelines on how to clean a helicopter. Bristow

Soap/detergent – some commercial detergents include additives which can damage aircraft;

Oxidisers – cause rapid corrosion to metals and seals – not good for aircraft;

Alcohol solutions – methanol and isopropanol have the advantage of evaporating quickly and are commonly used in aircraft but may have long-term effect on aircraft structures;

Quaternary ammonium compounds – are used in aircraft but can cause corrosion;

Acids or alkalis – need to be strong to work and are therefore bad for aircraft; and

UV radiation – needs 50 mins to work and is bad for elastomeric and polymeric products.

Helicopter operators (and indeed all aircraft operators) are now having to look in detail at the pros and cons of each alternative cleaning method and the best ways to use them for maximum effect against the virus and minimum damage to the aircraft.

Dutch described how the most effective method of cleaning was wiping surfaces which had the advantage of ensuring that all surfaces were treated but also so that the cleaning agent did not linger on surfaces which could be corroded. However, wiping surfaces is also very labour intensive and time-consuming. A quicker solution is low-level spraying or fogging but there is no control over where the cleaning agent goes.

The other speakers also agreed that aircraft cleaning was now an important issue. “We’ve never had to clean things so much,” declared Sam Schaab from Leonardo. “We have approved a variety of solutions and we’re looking at additional alternatives.” Schaab added that some customers have wanted to use UV-C lighting for decontamination but there has not been enough testing on its effect on aircraft parts, so there is a risk that it may degrade rubberised components.

Bristow has also prepared detailed guidelines on how its helicopters should be cleaned, including information on protective clothing, walking out to the aircraft, wiping and bagging of used materials and a checklist of tasks required in both the cabin and the cockpit.

Learning from experience

In conclusion, the speakers agreed that they had all been unprepared for the rapid onset and scale of the crisis. However, much progress had been made to adapt to the new ways of helicopter operation now needed to protect crew, medical staff, patients and aircraft during the Covid-19 pandemic. By working together to find rapid solutions, many lessons had been learned which would enable manufacturers, operators and regulatory authorities to be more prepared for similar situations in the future.

It’s not over yet

The final conclusion was that the advent of Covid-19 meant that the accepted rules had changed and nothing would ever be quite the same again. “We’re not through the woods yet,” stated Davitt Ward. “We’ve got to where we are by design, not luck. We’re still learning on the hoof and we need to keep an open mind. We’ve only survived first contact to cope with second contact, we’re going have to play a long game. We have to adapt our behaviours in order to live safely with Covid-19.”

A longer version of this report can be found on the AEROSPACE App

A CH-47 Chinook

helicopter, assigned to the

New York Army National

Guard makes a delivery

at a helipad in New York

City, April 2020. New York

National Guard members

are supporting the

multi-agency response to

Covid-19. US Air National Guard

A CH-47 Chinook

helicopter, assigned to the

New York Army National

Guard makes a delivery

at a helipad in New York

City, April 2020. New York

National Guard members

are supporting the

multi-agency response to

Covid-19. US Air National Guard