AIR TRANSPORT Pilot mental health

Mental health wellbeing for all

A recent RAeS conference looked at the issue of pilot mental health, what airlines were doing to implement new EASA/CAA regulations and how the lessons learned could be applied to the wider aerospace community. BILL READ FRAeS reports.

On 27-28 April the RAeS hosted a virtual conference on Mental Wellbeing and Human Performance: Moving beyond Regulatory Compliance. A follow-up from a previous conference held in May 2019 (the 2020 conference was cancelled due to Covid-19), the event looked at what has happened in the area of aviation personnel mental health and wellbeing over the past two years and what needs to be done in the future.

Figure 1. Tomas Klemets

Figure 1. Tomas Klemets

At the 2019 conference, the main topic of discussion was new European Union Safety Agency (EASA) safety rules on air operations introduced in 2018 following the fatal crash of a Germanwings A320 in 2015 (see Caring for pilots, February 2020). The new regulations include provisions designed to better support the mental health of air crew, including psychological evaluations for pilots, as well as support and reporting systems. However, the advent of Brexit in 2020 has meant that the UK is no longer governed by the EASA rules, although the rules will still be implemented by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA).

In addition to looking at pilots, the 2019 conference also examined the issue of mental health on aerospace professionals working in the wider aviation community – a theme which was developed further in this year’s conference.

Flying an aircraft is a stressful job and many pilots are subject to stress both from work and from personal reasons. “Pilots already had a tough job but it has been made even harder,” commented occupational psychologist Karen Moore. One cause of pilot stress at work is when they are expected to fly and for how long.

Kris Major

Chair for the Joint Aircrew Committee, European Transport Workers Federatio

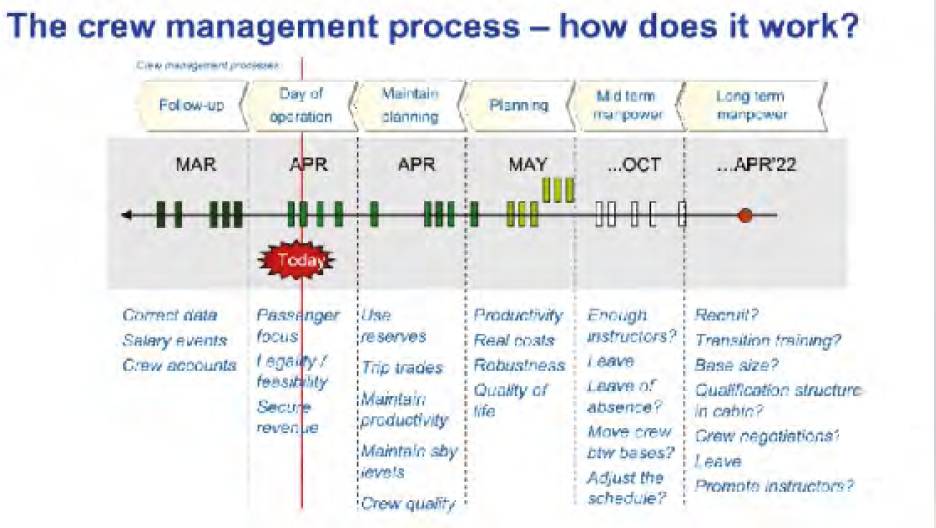

Tomas Klemets, Head of Scheduling Safety at Jeppesen, talked about the importance of pilot crew rosters and their effect on pilots (see Fig. 1). He explained that the way airlines created rosters was a complicated process. Airlines are trying to balance productivity (cannot have too few crew), real cost (layovers, transport, overtime), quality of life (time off), robustness (cover for illness) and fatigue risks. It is not possible to satisfy all these conditions so airlines need to compromise across all five areas. The planning begins with determining which flights would operate and then the crews needed to fly them. The rosters also have to account for different work patterns depending on pilots’ individual circumstances.

Pilots who are parents may only want to work on some days and always return to their home base, some pilots want to work with certain other flight crew and avoid working with others and some pilots want to have particular days off for holidays and so on. There is also the problem that, despite forward planning, it is not always possible to predict what flights will be needed. If an aircraft fails and needs to be replaced by another, it may also require a different flight crew. “If you change, for example, from an A320 to a 737, you can keep the cabin crew but you may need a different flight crew if pilots are not trained on that type,” said Klemets. “The more plans are changed unexpectedly, particularly at the last minute, the more stress is put onto flight crews.”

Flying an aircraft was already a stressful job but then along came Covid-19. Karen Moore

Flying an aircraft was already a stressful job but then along came Covid-19. Karen Moore

A new stress factor for pilots in the past 12 months has, of course, been the onset of Covid-19. Many pilots lost their jobs or were furloughed with no certainty that they would return to work. “The pandemic has increased the number of mental health problems,” admitted Kris Major, Chair for the Joint Aircrew Committee, European Transport Workers Federation. For those pilots who remained flying, there were other problems.

“The risk of infection has also meant that pilots also don’t feel safe at work,” said Captain Paul Reuter, Chairman, European Pilot Peer Support Initiative. Surprisingly, there were also benefits. “Pilots felt less stressed during Covid because they got decent sleep patterns,” observed Niven Phoenix, Director, Kura Human Factors

As Covid travel restrictions start to ease, pilots are beginning to return to work. However, many of those who have not flown for a while need to get used to being in a cockpit again. “There is a risk not just of ‘burn-out’ but of ‘rust-out’,” cautioned Marc Atherton who chaired the conference. “Pilots who are returning to work need to renew their skills.” There is also the risk of pilot shortages, as pilots – and other skilled air transport personnel – may have found work elsewhere. “We are losing talent at an astonishing rate,” said Paul Reuter. “We need to get it back.”

So, what can be done to reduce pilot stress?

Marc Atherton

Chair, RAeS Human Factors Wellbeing Group

The new EU/CAA rules require airlines to conduct psychological evaluations for pilots, as well as setting up support and reporting systems. However, it was felt by many speakers that some airlines were using the psychological evaluations not to help pilots but as a safety precaution. Some airlines were taking the view that pilots need to be screened for potential mental health problems and, if necessary, removed to avoid a repetition of the Germanwings incident. As a result of this, pilots often see their mental health as an issue not to be discussed or revealed to management to avoid losing their licences.

Regarding psychological assessment for pilots, Anna Vereker, Human Factors Programme Specialist at the CAA, explained how it was not intended to be a judgement on pilots’ mental health but was a means of robust selection to ensure that pilots are a good fit for an organisation. There were also concerns that many airline operators are concentrating their attention on other issues, with one speaker commenting that CEOs were more worried about money than mental health.

Figure 2. Paul ReuterAs for peer-group support programmes, the speakers were concerned that their effectiveness would be diminished if either management or pilots were not convinced by their value. One speaker highlighted an airline safety training programme which told pilots that if they said they were feeling suicidal, then they would lose their licence. “There is no point in having peer support which is filling holes which management has dug,” commented Niven Phoenix. However, he was convinced that peer-support programmes could bring benefits to both pilots and their employers. “Airlines may not be keen on spending money but peer support will help with reducing absenteeism and also ‘presenteeism’ – staying at work when you’re ill.”

Figure 2. Paul ReuterAs for peer-group support programmes, the speakers were concerned that their effectiveness would be diminished if either management or pilots were not convinced by their value. One speaker highlighted an airline safety training programme which told pilots that if they said they were feeling suicidal, then they would lose their licence. “There is no point in having peer support which is filling holes which management has dug,” commented Niven Phoenix. However, he was convinced that peer-support programmes could bring benefits to both pilots and their employers. “Airlines may not be keen on spending money but peer support will help with reducing absenteeism and also ‘presenteeism’ – staying at work when you’re ill.”

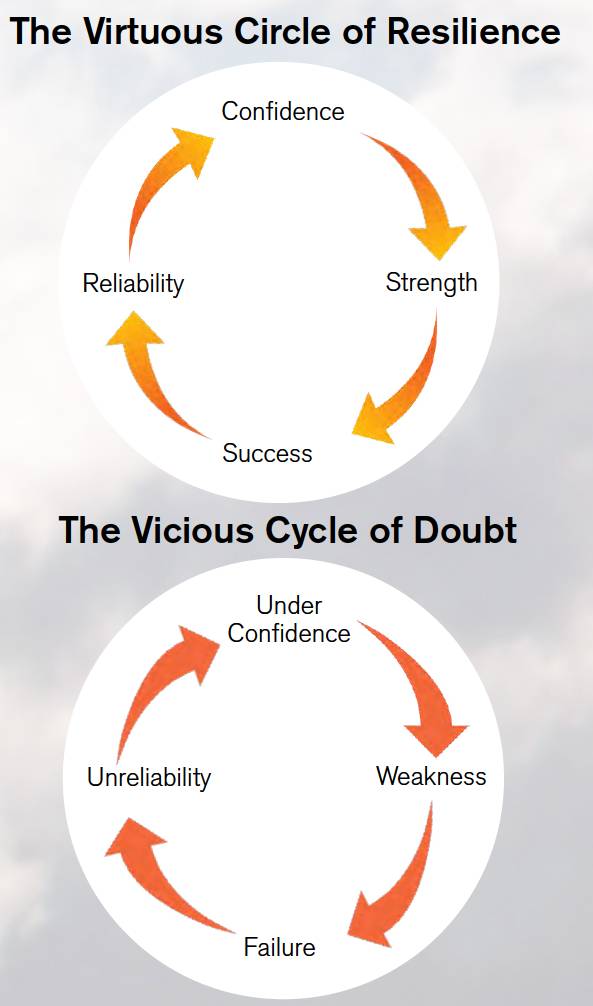

Another issue with peer support is what one speaker described as the ‘right stuff’ factor. “How do you know there’s a pilot at your party?” asked Paul Reuter. “Oh he’ll tell you.” Pilots have high personal and professional standards with a public image of always being calm, in control and able to deal with stress. “Pilots have a ‘virtuous circle of resilience reliability’ – confidence – strength – success,” said Reuter. “These are all good qualities – except when things go wrong (see Fig. 2).

However, the stresses and strains of both work and personal circumstances can pull down on that circle. Many pilots have sufficient resilience to bounce back.” He cited a survey which claimed that, when faced with an emotional cliff face, up to 25% of pilots will need a friend and a rope to get back up to where they were before. However, 5% of pilots don’t have a rope or refuse to have a rope, taking the view that it’s their problem and they don’t need help from others. “Pilots are not used to failure,” said Reuter. “If you fall, it hurts, you can’t cope, you’ve failed, there is a risk of losing your licence – pilots can slide very quickly into deep dark areas.”

Figure 3. While peer-support programmes can build bridges to help pilots regain confidence, pilots need to make the decision to use them. Paul Reuter

Figure 3. While peer-support programmes can build bridges to help pilots regain confidence, pilots need to make the decision to use them. Paul Reuter

The conference also addressed the issue of how to measure the scale of potential pilot mental health issues. Getting data on how much pilots are affected by mental health issues is not easy, as pilots are reluctant to speak out. “We need to focus on evidence but industry doesn’t have a clear take,” said Dr Joan Cahill, Principal Investigator at Trinity College Dublin. “The big challenge is to make workers feel comfortable about providing evidence.” “We need to speak openly and remove the fear of using certain words, such as depression and mental health,” added Paul Cullen, Research Assistant, Trinity College, Dublin. There were also concerns from pilots on how the data might be used. “It needs to be dealt with in a secure non-identifiable way,” declared Tomas Klemets. “The focus of current data is on what employees are doing and thinking but we need information on organisations too,” agreed Joan Cahill. “We need to decide what data we need to estimate wellbeing.”

A recognition of stress is crucial, not just for pilots and air traffic controllers but also for cabin crew, MRO engineers, airport workers and ground handlers. Bill Read/RAeS

A recognition of stress is crucial, not just for pilots and air traffic controllers but also for cabin crew, MRO engineers, airport workers and ground handlers. Bill Read/RAeS

However, while airlines may be required by the new EU/CAA regulations to provide mental health support for pilots, the service will not be effective if it is not used by pilots or management is not convinced of its value. “People need to be in situations where they can own up to mistakes and organisations can learn from them,” said Paul Reuter. “Wellbeing is underpinned by organisational culture,” assented Joan Cahill. “We need to move from a culture of safety to a culture of health and safety.” “The key challenge for management is gaining trust from employees,” remarked aviation psychologist at Isavia ANS, Jóhann Wium. “However, management also need to trust their employees not to misuse the system.”

The issue of mental health is also becoming a legal issue for organisations. Gerard Forlin QC explained how the onset of Covid had led to an increase in work risk assessment. “Stress is becoming an important word,” he warned. “Health and safety violations don’t need a death, just a risk. The prosecution of stress-related incidents is only a matter of time. If your audits pick up that you have knowledge of a problem before an incident and did nothing about it, then it will be used as evidence against you.”

Introducing mental health support for all air transport workers could help to improve safety for all air transport users. Bill Read/RAeS

Introducing mental health support for all air transport workers could help to improve safety for all air transport users. Bill Read/RAeS

In some sectors of the aviation industry, stress management training is already mandatory. Jóhann Wium described how the EU introduced new regulations in 2017, requiring stress management training for air traffic controllers. Wium explained how ATCs were not keen on discussing stress: “Controllers felt that being able to handle stress was seen as a point of pride while not handling stress was bad and not to be talked about. Our solution was to create workshops with optional self-assessment. The answers were anonymous. As a result, ATCs built an awareness of stress, its effects and how to cope with it, so that it was no longer seen as a negative thing.” Wium added that the ATC experience had been good, although it had to be careful to take a fine line between supporting and snooping.

Stress management training is already mandatory for ATC personnel. Bill Read/RAeSThe speakers agreed that a recognition of stress was crucial, not just for pilots and air traffic controllers but across all safety-critical groups in the aviation industry, such as cabin crew, MRO engineers, airport workers and ground handlers. “We can’t compartmentalise aviation safety,” said Kris Major. “Peer support need to include more than just pilots.”

Stress management training is already mandatory for ATC personnel. Bill Read/RAeSThe speakers agreed that a recognition of stress was crucial, not just for pilots and air traffic controllers but across all safety-critical groups in the aviation industry, such as cabin crew, MRO engineers, airport workers and ground handlers. “We can’t compartmentalise aviation safety,” said Kris Major. “Peer support need to include more than just pilots.”

However, much still needs to be done to convince employees of the advantages of a mental health support programme. “People won’t remove themselves from operations because they fear punitive measures,” warned Major. “In ground handling, the fear factor is huge. Workers have a fear of management and you don’t get incident reports because people are too frightened to submit them.”

“We need to focus not just on pilots but on the whole industry,” declared Marc Atherton. “We need to promote a positive cultural shift to create a positive and safe operational environment where everyone feels supported and safe.” “If you take care of staff, it will not just have an influence on safety but positively influence the whole company,” assented Paul Reuter.

“We have not reached the pinnacle of safety,” warned Kris Major. “We can either do something about it or play Jenga by sitting on the regulations and thinking that they are adequate.”