SPACEFLIGHT Space debris – the legal questions

Does this spark joy?

A case for decluttering and tidying orbital space junk

MELISSA TANG and PATRICK SLOMSKI of global law firm Clyde & Co consider the legal ramifications of the growing challenge of space debris.

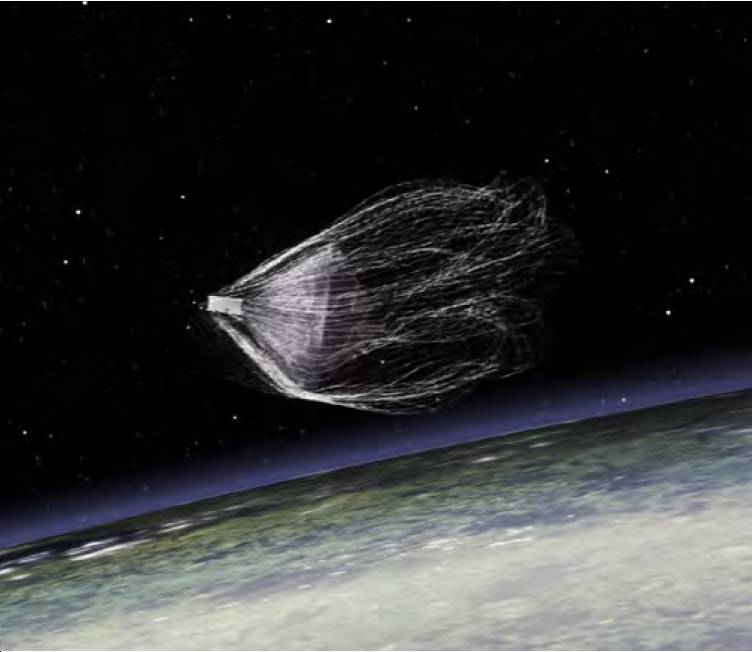

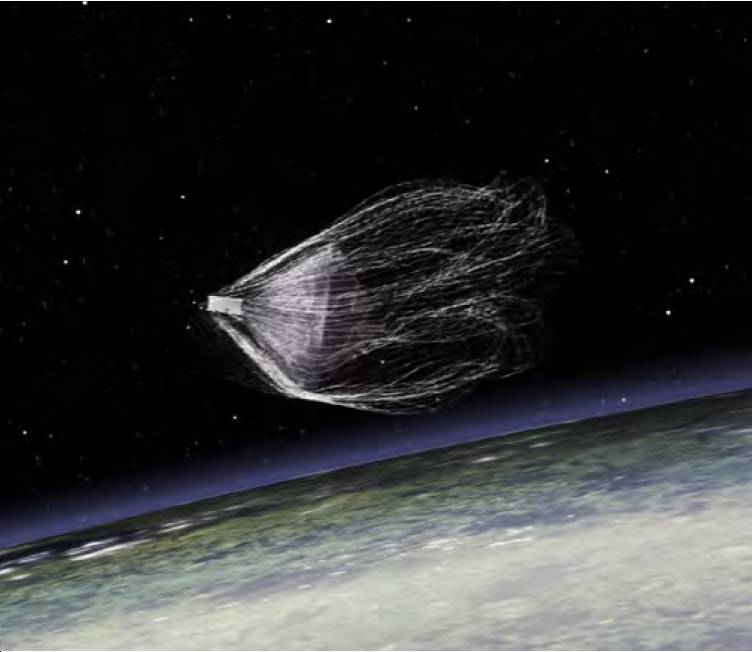

This image shows how a net capture of space debris might be carried out. Surrey Space CentreIn the 60 odd years of space exploration following the Soviet Union’s launch of its first satellite in 1957, space has become increasingly cluttered with derelict satellites, burnt-out rocket stages, discarded trash and other debris, prompting NASA to refer to the lower earth orbit (LEO) as an ‘orbital space junk yard’.

This image shows how a net capture of space debris might be carried out. Surrey Space CentreIn the 60 odd years of space exploration following the Soviet Union’s launch of its first satellite in 1957, space has become increasingly cluttered with derelict satellites, burnt-out rocket stages, discarded trash and other debris, prompting NASA to refer to the lower earth orbit (LEO) as an ‘orbital space junk yard’.

The commercial use of space is growing at an increasing rate. The launch of ‘megaconstellations’ which can comprise thousands of small satellites will increase the problems associated with orbital debris. Space debris travels at very high speeds such that even a collision with a small piece of debris (eg a fleck of paint) can damage or destroy working satellites, threaten space missions, and create new debris fragments.

There is growing international recognition of the need to deal with orbital debris and to provide an adequate international framework to address the complex legal issues that it raises. Current space treaties do not provide an effective framework to regulate the issue of orbital debris and there is no effective international law regime regarding responsibility to mitigate debris creation, or the remediation of the orbital environment (and who bears the costs). Liability for damage caused by debris raises complex legal issues, with much interpretation left to individual entities (and their lawyers).

Why should we care about the management of orbital debris?

Space is vast. Earthling space activities are currently primarily limited to three orbital regions: LEO, medium Earth orbit (MEO) and geostationary orbit (GEO). We are increasingly relying on satellite technology for meteorology, geology, climate research, telecommunications, navigation, remote sensing and human space exploration purposes. Assisted by lower per-launch costs and cheaper satellite development, the number of satellites being manufactured and launched into LEO has increased.

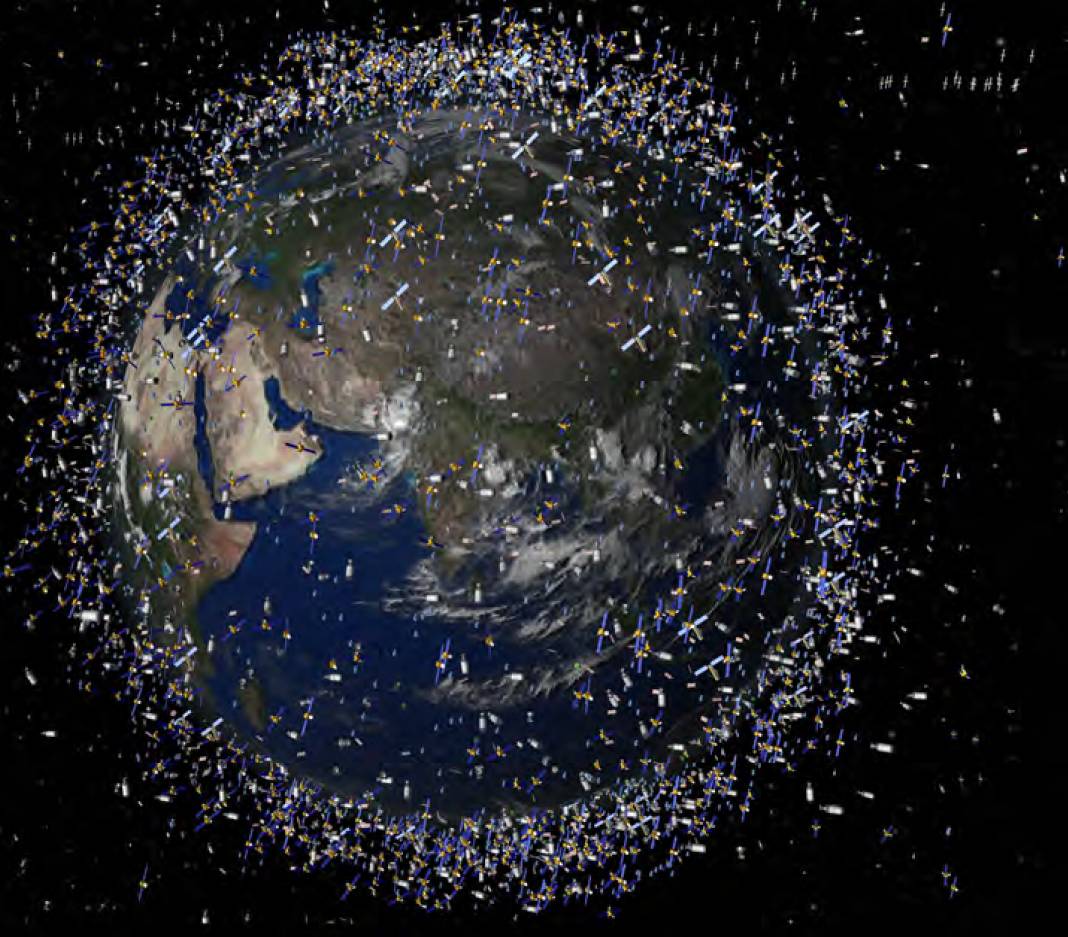

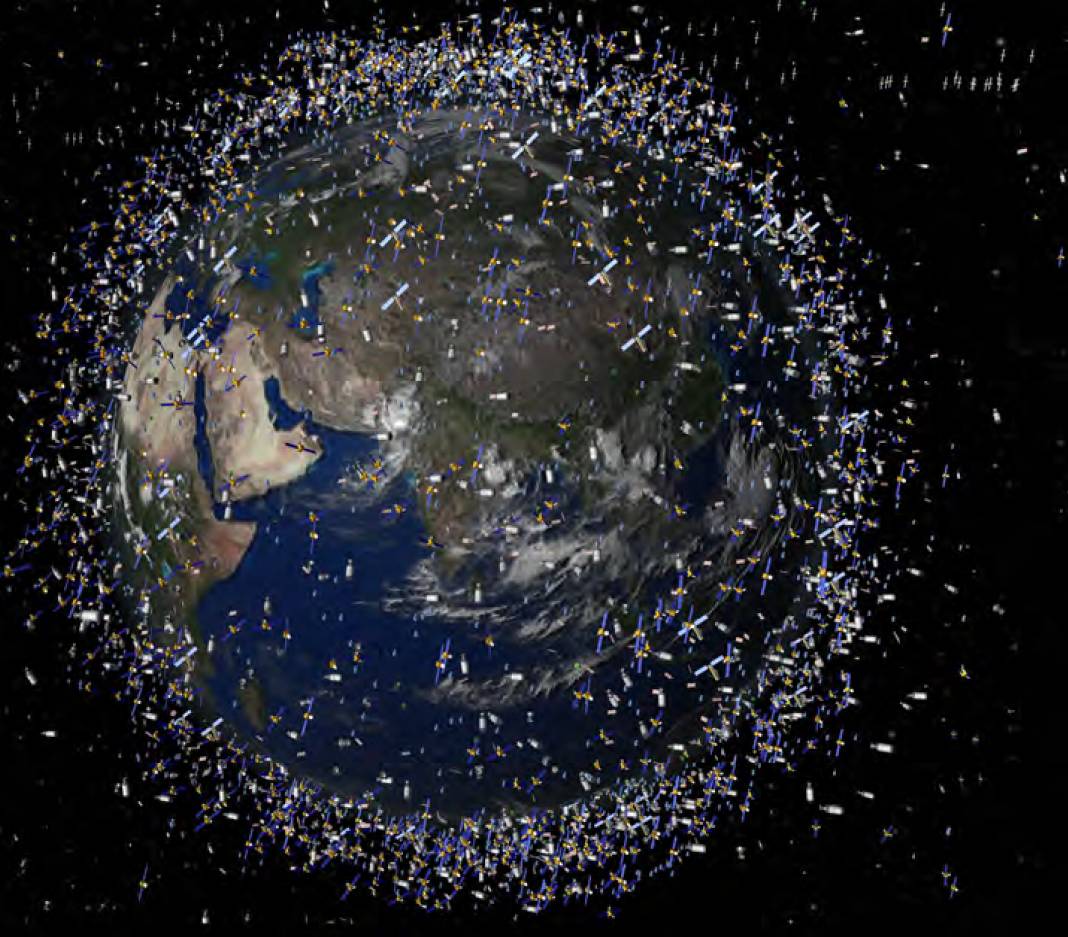

An artist’s impression of space debris currently orbiting Earth. ESACommercial companies such as SpaceX, Google and Amazon are competing to deploy ‘mega constellations’ of internet satellites in LEO to provide affordable and reliable internet connectivity. NASA has signalled continuing ambitions to partner with the private sector to develop new space activities in LEO focusing on cargo and crew transportation, and eventually, industrialisation.

An artist’s impression of space debris currently orbiting Earth. ESACommercial companies such as SpaceX, Google and Amazon are competing to deploy ‘mega constellations’ of internet satellites in LEO to provide affordable and reliable internet connectivity. NASA has signalled continuing ambitions to partner with the private sector to develop new space activities in LEO focusing on cargo and crew transportation, and eventually, industrialisation.

The expected commercialisation of space beyond aerospace and defence adds to the ongoing challenge of managing orbital debris. Currently there are more pieces of space debris in LEO than operational satellites with the European Space Agency’s Space Debris Office likening it to ‘driving down a road which has more broken cars, bikes and vans lining the street than functioning vehicles’. As of 20 May 2021, the European Space Agency estimates that there are 34,000 debris objects larger than 10cm along with 900,000 debris objects between 1cm to 10cm currently in orbit around Earth. Most of the debris objects comprise mission-related debris release and fragmentation debris from accidental collisions and intentional destruction of satellites (such as the anti-satellite weapon test by China in 2007).

Space debris can remain in orbit for a very long time depending upon its size, nature, and altitude. The higher the altitude, the longer the orbital debris will typically remain in the Earth’s orbit. At typical collision speeds of 10km/s in orbit, subject to the size of the debris, a collision with space debris has the potential to accelerate the degradation of operational satellites, critically damage or destroy operational satellites and threaten space missions, including the International Space Station.

In 2020, the International Space Station (which resides in LEO) was forced to manoeuvre its path three times to avoid potential collisions with space debris.

EVEN A COLLISION WITH A SMALL PIECE OF DEBRIS (EG A FLECK OF PAINT) CAN DAMAGE OR DESTROY WORKING SATELLITES, THREATEN SPACE MISSIONS, AND CREATE NEW DEBRIS FRAGMENTS

As not all orbital debris is trackable, it may not always be possible to manoeuvre away from a collision. There is also a risk that rocket bodies and satellites that do not disintegrate fully before re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere can cause potential safety and environmental threat to objects on Earth as highlighted by the recent uncontrolled re-entry of China’s Long March 5B in May 2021.

Unless standardised and binding mitigation measures are adopted at the international level, the amount of space debris in LEO will continue to rise, impacting the viability of future space exploration. The partial or complete loss of access to LEO also endangers launches to higher orbits, GEO and MEO, and there is the threat of eventually falling foul of the Kessler syndrome. The Kessler syndrome posits that at a certain point, collisions between space debris could cause a cascading effect leading to exponential increase of space debris.

Current regulatory and legal environment

There is no effective ‘hard law’ or mandatory regime regulating the issues of orbital debris in current international law. Although many states legally require debris mitigation measures as part of their licensing process for space launchers and operators, adherence to the debris mitigation measures developed (such as the Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space) are voluntary. As private commercial space activity increases, there are growing concerns that the existing international law framework is insufficient to regulate space debris.

Three treaties with potential relevance to the issue of space debris are the:

- 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of states in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space (Outer Space Treaty)

- 1972 Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (Liability Convention)

- 1976 Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space (Registration Convention)

Article VI, VII and IX in the Outer Space Treaty contain language that might be used to support an argument that signatory nations are obliged to avoid the creation of, reduce, and even remove, space debris to allow all states to participate in the exploration and the use of outer space with acceptable risk from debris. However, whether the provisions are intended to encompass space debris may be vigorously debated, as the provisions are vague.

The Liability and Registration Conventions are relevant to the liability of signatory states for damage caused by their space objects.

Article III of the Liability Convention deals with damage that occurs in outer space and makes signatory nations liable to other nations for damage caused by space objects for which they are the ‘launching state’. Nations are responsible and may be held liable for the commercial activities of their citizen private companies in space, including (arguably) for the consequences and resulting damage of space debris created by those activities.

While the Liability Convention may cover damage caused by orbital debris, there are difficulties establishing liability under that regime. For compensation to be payable, a victim nation must demonstrate ‘fault’, causation, and damage. The Liability Convention does not define ‘fault’ and there is uncertainty whether the standard of care to which the wrongdoer should be held equate to the common law or civil law standards of fault. The uncertainty is compounded by the lack of mandatory international standards of conduct regarding debris mitigation in space. Commentators have advocated for a strict liability system as an alternative to a fault-based system for in-orbit damage, and such regimes (with liability limitations) have been used in other areas of human endeavour to foster the expansion of commercial operations, such as in international aviation (for example).

Another obstacle associated with fault-based liability is the difficulty of proving a causal connection between the debris-causing ‘accident’ and damage. The most practical problem in establishing liability for damage caused by orbital debris is proving who is responsible for its generation. The Registration Convention seeks to provide for information to assist with determining liability by mandating that all ‘launching states’ maintain a register of objects launched into space. Article VI of the Registration Convention directs nations with monitoring or tracking facilities to aid in the identification of space objects that cause damage. However, proving that damage has been caused by space debris may be difficult. It may not be possible to trace the damage to orbital debris or to the owner of the debris-generating launched object. Currently, only space debris larger than 10cm is tracked and catalogued. Therefore, the origin of smaller pieces of orbital debris, that cannot be tracked or catalogued by the launching state, is likely to be uncertain.

There is then also the issue of whether it can be said that the launcher of the debris-generating object was at ‘fault’; for example, the if the debris generation was as a result of collision of uncontrolled objects (or debris!). As with many of the questions and issues surrounding the subject, that is an untested question.

There is also a question of who has jurisdiction to hear space debris claims and of the law applicable to any such claim in private national law. This gives rise to a ‘patch-work’ of domestic legal regimes that would be applied, varying from nation to nation across the world.

The Liability Convention only applies to states and each country has authority to make laws regulating various outer space activities by their nationals. While the Liability Convention scheme focuses on diplomatic solutions to address claims caused by a space object, Article XI leaves open the possibility for claims to be brought before the national courts or administrative tribunals or agencies of a launching state. Article XXIII of the Liability Convention also allows states to enter into their own agreements without interference from the Liability Convention.

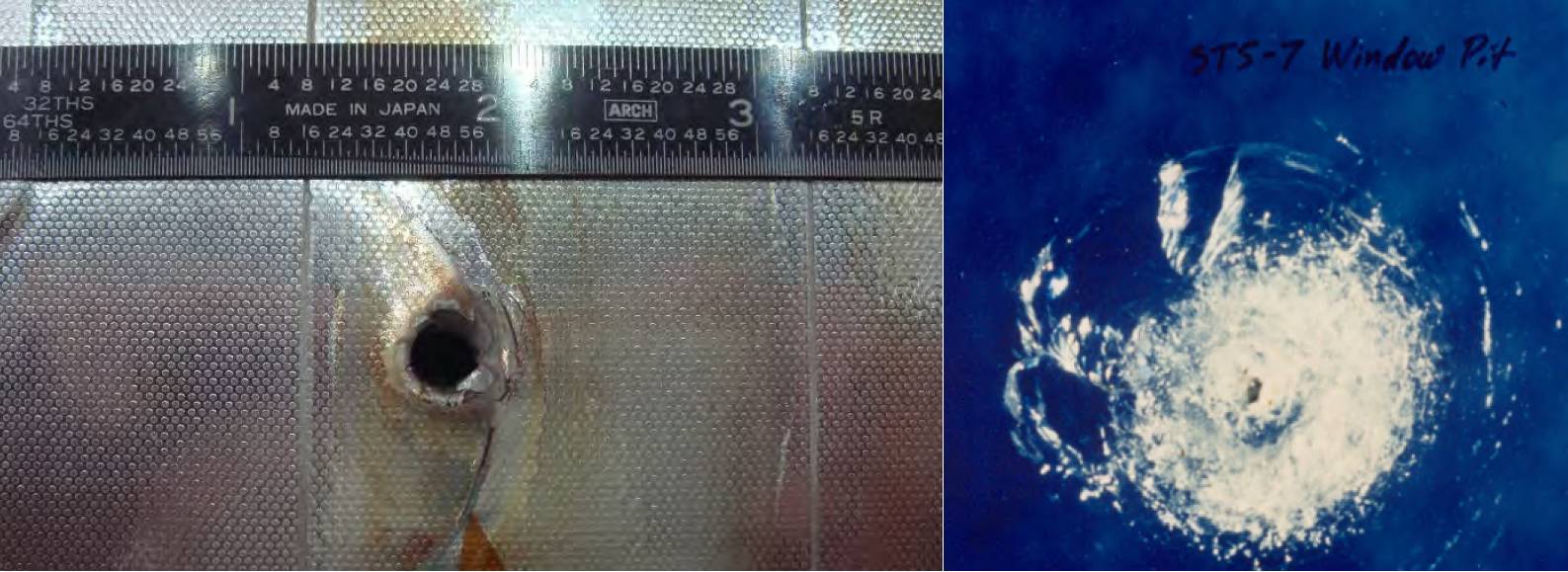

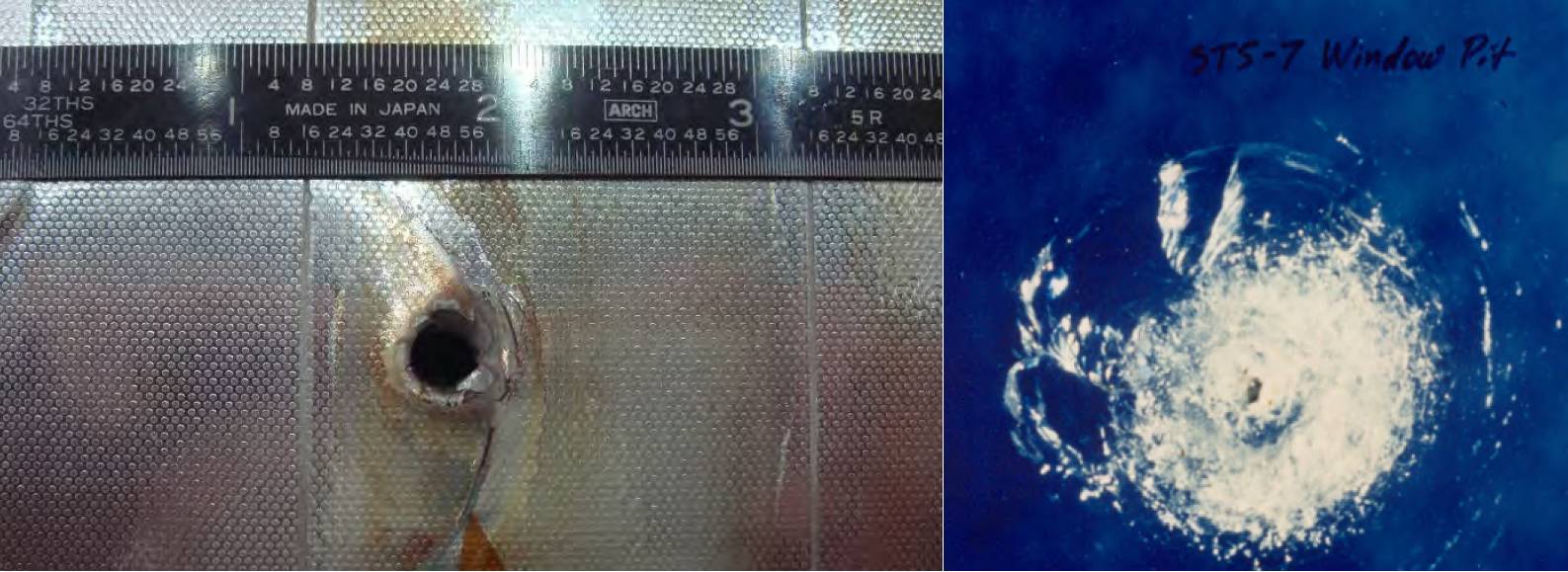

Above left: Entry hole created on Space Shuttle Endeavour’s radiator panel by the impact of unknown space debris. Above right: An impact crater on one of the windows of the Space Shuttle Challenger following a collision with a paint chip. NASA

Above left: Entry hole created on Space Shuttle Endeavour’s radiator panel by the impact of unknown space debris. Above right: An impact crater on one of the windows of the Space Shuttle Challenger following a collision with a paint chip. NASA

The Liability Convention establishes joint and several liability when there is more than one launching state. The existence of multiple launching states increases the available jurisdictions for disputes for orbital damage claims to be brought. In the absence of an international convention or other international legal regime providing a clear liability regime for damage caused by orbital debris, national laws will most likely be applied in respect of claims arising from private commercial space activities. Against this backdrop, the potential for different national laws and legal regimes to apply creates ample opportunity for parties (and their lawyers) to engage in extended argument over which jurisdiction is appropriate and which law should be applied.

In addition to the liability challenges raised, the lack of a clear mechanism for dispute resolution in the Liability Convention and the need to involve signatory nations to bring claims against other nations on behalf of private operators for whom they are responsible, has inevitably resulted in the Liability Convention not being commonly used or relied upon. There has yet to be a claim on the basis of damage occurring while in orbit. The Liability Convention has not been widely applied; the only instance of a formal claim arose out of the re-entry of a Russian spacecraft which caused radioactive debris to be scattered on Canadian territory. The claim was settled by diplomatic means.

The possibility of having numerous dispute resolution avenues and applicable laws raises the spectre of uncertainty, and a very significant barrier to enabling wider commercialisation of orbital space. Without an adequate legal international framework addressing the regulation of orbital debris and liability issues, an operator suffering loss in orbit will face very significant issues when seeking to recover compensation for damage caused by orbital debris. Such a regime may also provide for the cost of remediation of this arena for new commercial endeavour.

Conclusion

SPACE-FARING NATIONS MUST TAKE THE LEAD TO GARNER INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF BINDING INTERNATIONAL LAWS AND POLICIES

As discussed above, the current legal regime is inadequate to address liability and complex issues related to space debris collision. The spacefaring nations must take the lead to garner international co-operation on the development of binding international laws and policies to address the growing space debris problem. Given the scale of the debris problem, any inaction will impact the long-term sustainability of space activities and fail to preserve Earth’s orbital space as the common heritage of all mankind.

The law (both international and domestic) in this growing area of interest remains untested and unclear and therefore, has the potential to be of great importance to current and future users of space. It is a topic that needs to be watched carefully and clarified for the benefit of all concerned.

This image shows how a net capture of space debris might be carried out. Surrey Space CentreIn the 60 odd years of space exploration following the Soviet Union’s launch of its first satellite in 1957, space has become increasingly cluttered with derelict satellites, burnt-out rocket stages, discarded trash and other debris, prompting NASA to refer to the lower earth orbit (LEO) as an ‘orbital space junk yard’.

This image shows how a net capture of space debris might be carried out. Surrey Space CentreIn the 60 odd years of space exploration following the Soviet Union’s launch of its first satellite in 1957, space has become increasingly cluttered with derelict satellites, burnt-out rocket stages, discarded trash and other debris, prompting NASA to refer to the lower earth orbit (LEO) as an ‘orbital space junk yard’. An artist’s impression of space debris currently orbiting Earth. ESACommercial companies such as SpaceX, Google and Amazon are competing to deploy ‘mega constellations’ of internet satellites in LEO to provide affordable and reliable internet connectivity. NASA has signalled continuing ambitions to partner with the private sector to develop new space activities in LEO focusing on cargo and crew transportation, and eventually, industrialisation.

An artist’s impression of space debris currently orbiting Earth. ESACommercial companies such as SpaceX, Google and Amazon are competing to deploy ‘mega constellations’ of internet satellites in LEO to provide affordable and reliable internet connectivity. NASA has signalled continuing ambitions to partner with the private sector to develop new space activities in LEO focusing on cargo and crew transportation, and eventually, industrialisation.