AIR TRANSPORT Investing in safety

Beyond safety

The Royal Aeronautical Society HUMAN FACTORS in FLIGHT OPERATIONS and TRAINING GROUP explains, why, despite these unprecedented times, aviation organisations need to aim to exceed, not just meet safety standards.

American Airlines

American Airlines

In these unprecedented times for the aviation industry, many airlines are desperately trying to survive and are reviewing the investments they make in different areas of their operation. So, what are the considerations that drive investment in the airline industry? Load factors, certainly. Profit, most definitely. Safety, absolutely. Since the advent of human factors (HF) and, more specifically, crew resource management (CRM), safety and training departments within airlines have made their case for investment in this area on the basis of improving safety.

Demonstrating a return on investment in safety-related areas can be difficult because the endpoints which demonstrate success can be far more abstract and nebulous than the bottom line. An investment in marketing, for example, can be seen to have worked if there is an increase in public awareness of the company and a corresponding increase in sales. An investment in a safety-related project can have far less distinct markers of success. Is it an absence of accidents or incidents? These are usually rare enough that their perceived absence may be a statistical anomaly. A decrease in safety reports? Perhaps something has happened in the company that has made employees less likely to file reports. These problems can often make it tricky for operators and instructors at the sharp end of the organisation to convince stakeholders to make, maintain or increase investment in these areas. The best organisations account for this and invest anyway and it is to their credit that they do. However, in this article we hope to demonstrate that there are tangible benefits to investing in human factors beyond improving safety.

Investing in people

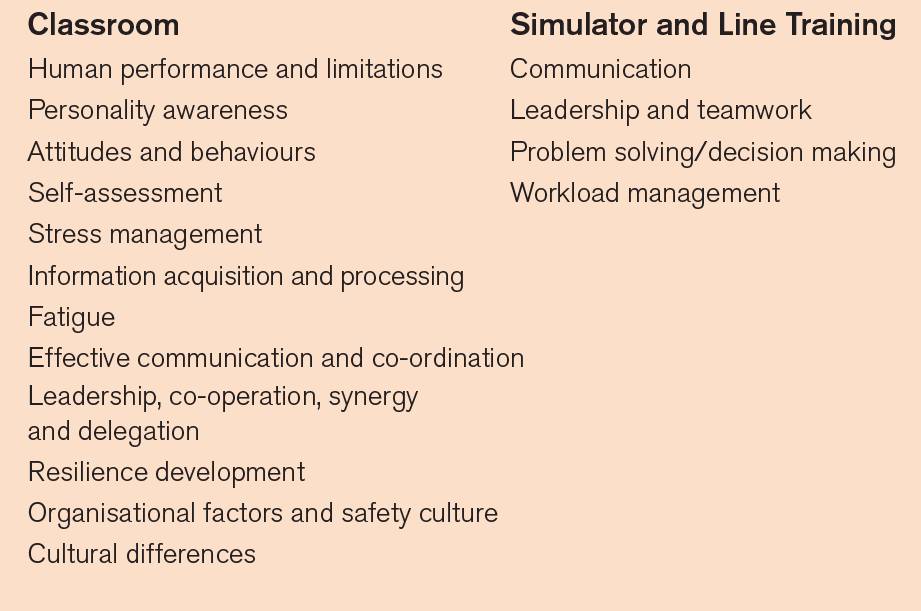

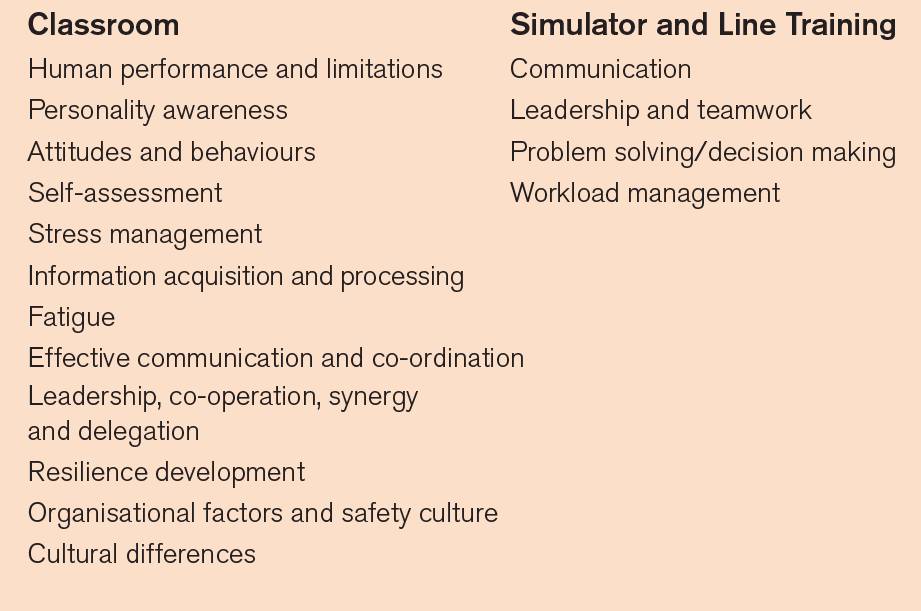

In order to define the scope of this article a little more clearly, we are looking at the non-safety related benefits of CRM/HF training in airlines. The table below shows a selection of the topics/ competencies in the regulatory guidance that are required to be covered during classroom, simulator and line training for pilots and cabin crew. These topics have been selected as they illustrate how this kind of training can confer benefits to the airline in addition to improving safety:

To construct this article, the members of the Royal Aeronautical Society standing group for Human Factors in Flight Operations and Training were asked to look into ways in which investment in human factors training benefits organisations with the exception of the obvious safety benefits. As we have worked on this as a team, it is being published without the names of the individual members.

Operational efficiency

Operational efficiency

When managing non-normal situations on board aircraft, in all likelihood one of the decisions which will need to be made either explicitly or implicitly is whether the flight will continue, divert or return to the departure airport. Such situations may arise because of technical failures, changes in the weather or, indeed, events in the cabin (medical issues, disruptive passengers, etc). In all but the most critical emergencies (for example, where getting to an airport is not an option), the flight will do one of these three things – continue, divert or return. Experienced pilots will be aware that there are a huge number of variables that affect this decision but, as any simulator instructor will tell you, different crews often arrive at different conclusions based on how they have carried out the decisionmaking process.

A technical failure resulting in an increase in the length of runway required for landing may lead crews to seek out the longest runway available, irrespective of whether that runway is at an airport served by their airline, is close to the planned destination or has effective engineering support which will get the aircraft back into service again quickly. A more nuanced decision-making process that factors in the input from ground operations, engineering support and flight operations control may lead crews to select an airport with a shorter runway (but still long enough to land safely) but which offers far more chance of getting the passengers to their destination efficiently and the aircraft back into operation quickly. All other things being equal, a longer runway is theoretically ‘safer’ than a shorter one (for example, a grossly unstable approach that lands well outside the touchdown zone would have a better chance of avoiding an overrun on a longer runway).

Why then would it be acceptable for crews to land on a shorter one? The nature of commercial aviation requires operators to balance safety and efficiency. It is theoretically safer from a fatigue point of view that pilots only operate one flight per day. However, this would be highly inefficient and so, a trade-off between efficiency and safety needs to be made. A longer runway may be safer but this doesn’t necessarily mean a shorter runway is ‘unsafe’. If a landing distance calculation can be made accurately and the input of other parties be solicited, a robust and defensible decision may be to continue to the planned destination or divert to an airport that is an engineering base and offers transit links for the passengers, despite it not having the longest runway of the potential diversion options.

The role of the airline is to make sure that crews are equipped with tools to allow them to make these decisions and to ensure that they are trained to use them effectively. Formal decisionmaking tools can be taught in the classroom and reinforced in the simulator and on the line. These skills may also be of benefit to employees in other departments and several members of the Human Factors Group who work with organisations in this way have reported great success when training groups comprising employees from all departments within the organisation, not only the flight operations department.

Crew management, absenteeism and retention

Estimates suggest that the number of pilots and cabin crew working in the aviation industry preCovid-19 amount to just over one million. That number approaches two million when other airline employees are included. The working environment on an aircraft is somewhat unique given that one crew member must work for extended periods of time and in close proximity to other crew members whom they may have only met for the first time at the start of the duty. In other environments, one gets to know one’s colleagues and this increasing familiarity can help the working relationship, as people get accustomed to each other’s personalities. In the dynamic, multi-cultural, multi-generational, increasingly diverse and frequently stressful world of commercial aviation, this familiarity may be missing, which presents a greater opportunity for misunderstanding and, potentially, conflict.

THE CULTURE OF AN AIRLINE, OR A BASE WITHIN AN AIRLINE, MAY BE SUCH THAT CREW ENGAGE IN TIT-FOR-TAT REPORTING OF COLLEAGUES WHICH INCREASES WORKLOAD FOR CREW MANAGERS.

While such conflict will have an adverse effect on team cohesion and overall safety, it can spill over into more formal recrimination. The culture of an airline, or a base within an airline, may be such that crew engage in tit-for-tat reporting of colleagues which increases workload for crew managers. The European syllabus for CRM training contains many topics which relate to this problem and the regulations give operators quite a lot of scope in how they cover these topics. For example, a training session on ‘effective communication’ may include guidance on how best to give feedback. A session on ‘leadership and co-operation’ may cover guidance on conflict solving. These are skills that not only have safety advantages when employed in non-normal situations but can also equip airline employees with the tools they need to successfully manage other work-related difficulties without the need for higher-level intervention. Employees who are well-trained in these areas are more likely to have the capacity to deal with complex, dynamic situations. This ability increases the resilience on the individual level and, once well established, increases the resilience of the team/s that employee is a part of and, ultimately, the organisation as a whole.

Reducing absenteeism

Reducing absenteeism

Absenteeism due to stress and fatigue can be partly addressed through CRM training and other related human factors interventions. Employee morale and the perceived friendliness of the workplace is undoubtedly going to affect an individual’s level of work-related stress. Since the advent of fatigue risk management, crew are a lot more aware of how best to ensure they get an adequate amount of restful sleep. Additionally, peer support programmes are being introduced across the industry. Some organisations are going further than the regulations require and are implementing them for all staff, not only flight crew. This investment clearly demonstrates a commitment towards employee’s well-being. A study by Deloitte found that, for every £1 an employer invests in mental health and wellbeing programmes for their employees, they receive a £5 return on that investment through decreased absenteeism and increased productivity and retention.

There are significant costs connected with the turnover of crew in an airline associated with the recruitment and training processes, as well as the time that this takes. Some studies suggest that the cost of replacing a pilot may be 50% of that pilot’s annual salary and that some companies experience a turnover of more than 30% of their workforce annually. Various studies in aviation and non-aviation companies have tried to determine the factors that affect an individual’s desire to leave a company. In one study of airline pilots, job satisfaction was a stronger predictor of a pilot’s intention to leave a company than annual salary alone. In this study, job satisfaction increased with factors such as organisational commitment, supportive management and interpersonal relationships. For example, an organisation that can demonstrate a commitment to improve and invest in safety will reap the additional benefit that this demonstration of commitment brings to employee job satisfaction.

Embraer

Embraer

Brand reputation and customer engagement

Airline employees, especially cabin crew, are increasingly aware that potentially any inflight event may end up being recorded by one or more passengers. The announcements made by pilots and cabin crew, how the crew appear to interact with each other and how passengers are treated may all be uploaded to social media and beyond incredibly quickly. As such, the performance indicators which demonstrate the presence (or absence) of particular human factors competencies may be on display to the world. In one particular case, would greater cultural awareness have prevented a pilot from suggesting that passengers pray for a successful landing? Conversely, the actions and behaviour of the cabin crew of Asiana Flight 214 that crashed on approach to San Francisco International were widely and positively reported in the media. There have also been cases where disagreements between crew members have become apparent to passengers with some media reports of physical aggression between crew members in flight.

Only with an understanding of passenger and crew human factors can the next generation of ultralong-haul flights be successful. Qantas has recently been investigating this in advance of its planned ultra-long-haul flights from Sydney to Europe and the east coast of the US. Project Sunrise was established to determine how to maximise crew and passenger well-being during ultra-long-haul flights, although Covid-19 means this project may well be delayed.

Conclusion

It can be difficult to present evidence for the safety benefits of CRM training. It can be even harder to do so for the non-safety-related benefits. The skills taught in the classroom and consolidated in the simulator and on the line are elaborations on what we do every day.

We all make decisions but how well do we make them? We all have to manage disagreement in the workplace but how well do we manage it? There is no denying that CRM training came into being to address the human element in aviation accidents and incidents but it also presents another opportunity for us. It would be wrong to suggest that an airline should shift focus away from CRM training being primarily about improving safety but the techniques taught are more widely applicable. While it is good to know that crew have these skills at hand when things go wrong, these same skills can be applied far more frequently to benefit an airline beyond safety, a fact that might be useful to remember during these unprecedented times.

LinkedIn group: Royal Aeronautical Society Human Factors Group – Flight Operations and Training

American Airlines

American Airlines