SPACEFLIGHT Commercial satellite operators and ASAT

Wake-up call for space threats

As space gets more contested, ALLEN ANTROBUS FRAeS, Key Account Military Space for Airbus DS in the UK, assesses the impact of the increased militarisation of space for the commercial space sector.

ESA

ESA

The anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons test this summer, reported by the UK and US Governments, and denied by the Russians, is another indicator that in-orbit tests and direct ascent tests (DA-ASAT) appear to be on the rise. According to the Secure World Foundation, the Russians have conducted ten possible ASAT tests since 2014; over the same period, the Chinese have conducted four tests and the Indians two. This trend is worrying to all actors in space, including the UK space commercial sector.

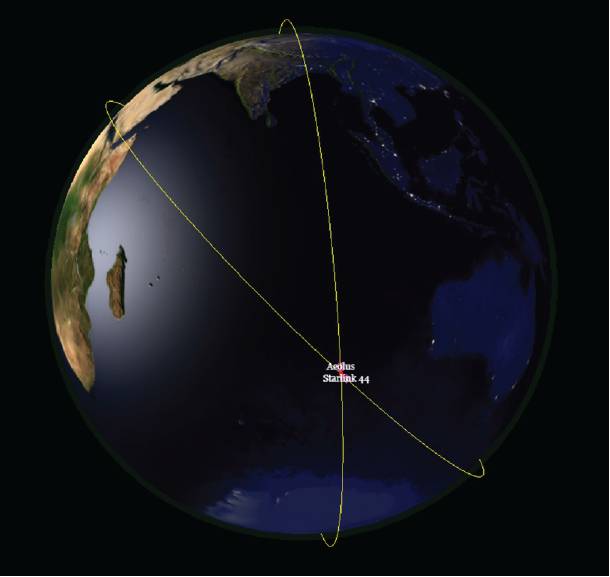

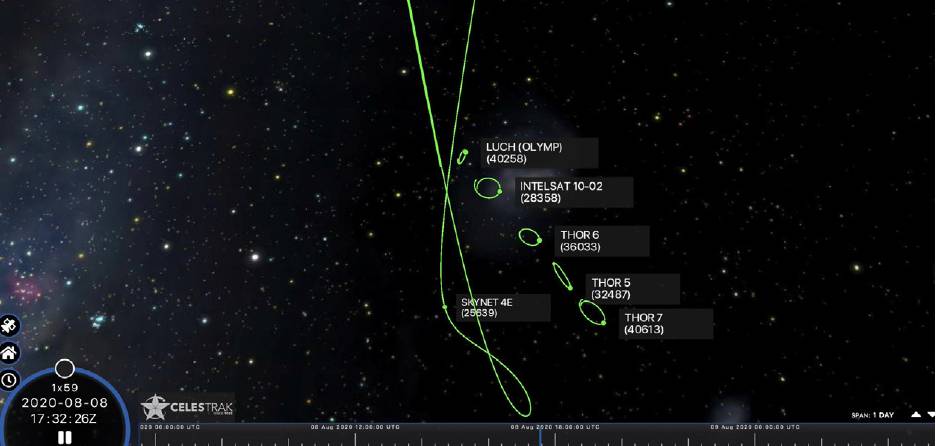

On 15 July 2020, a Russian military satellite, Kosmos 2543, released a high-speed projectile from the main body of the spacecraft and, although there was no indication the projectile collided with another satellite, this action, according to US Space Command, was ‘consistent with a test of a new anti-satellite capability’. This event followed a Russian DA-ASAT test on the 15 April 2020 from a system termed Nudol and which was launched from Northern Russia but again did not collide with another satellite. The Nudol system is designed to engage targets in low Earth orbit between the 150-2,000km above the Earth’s surface. Along with these ASAT tests, both the Russians and Chinese have engaged in orbit behaviour that could be interpreted as aggressive. In 2014, a Russian satellite called ‘Luch’ manoeuvred around the geostationary belt and came close to both French and Italian military communication satellites. More recently, from July 2017 to December 2019, a Chinese satellite SJ-17 made a series of manoeuvres in the geostationary belt and conducted a series of space rendezvous with a number of other Chinese satellites; these manoeuvres took SJ-17 past the UK MoD’s Skynet 5A satellite.

Russian satellite ‘Luch’ and the UK’s Skynet 4E satellite. CelesTrak

Russian satellite ‘Luch’ and the UK’s Skynet 4E satellite. CelesTrak

Space has always been the preserve of the military and intelligence services of the US and Russian (previously the USSR) governments but, since the mid-1980s, there has been little overt testing of anti-satellite weapons. The status quo changed when the Chinese government shot down a defunct weather satellite (Fengyun-1C) on 11 January 2007. This destructive event created over 3,000 pieces of debris and was widely condemned by the international community. Since then, the US, Russia and, more recently, the Indians have conducted tests, as well as rendezvous and proximity operations (RPO), which could be interpreted as a test run for possible military action. International law and treaties offer little advice or guidance on how to interpret these actions. Article IV of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 declares that: ‘Parties to the treaty undertake not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction’. Consequently, as the treaty only mentions nuclear weapons and WMD, then it could be interpreted that other types of weapons are allowable. Any misinterpretation on the use of RPO or anti-satellite tests could have grave consequences for the UK space sector but also the wider UK economy.

Space assets have significantly changed the way we live our lives on Earth. Position, navigation and timing data from the US GPS constellation or the EU’s Galileo constellation have transformed the transport and financial sectors that enable ‘just-in-time’ supply chains, support millions of pounds of global financial transactions and synchronisation of everything from utility networks to mobile phone systems. Accurate data from meteorological satellites have transformed the way farmers cultivate the land reducing waste and improving food production. Large satellites, over 36,000km above Earth, broadcast news and sports direct to our home. In the not too distant future, megaconstellations such as OneWeb will provide broadband services direct to homes and this will enable those of us who live in remote locations to benefit from ‘fibre-like’ speeds from space. All of this is at risk if a conflict between nations extends into space.

Satellite mega constellations such as OneWeb are set to bring benefits but also increase congestion in orbit. OneWeb

Satellite mega constellations such as OneWeb are set to bring benefits but also increase congestion in orbit. OneWeb