AIR TRANSPORT Neurodiverse air travel

Flying with autism

BILL READ FRAeS and JENNIFER READ look at the issues faced by autistic air travellers and what can be done to help them.

In recent years there has been an increased focus on the needs of physically disabled transport users and improvements have been made to transport infrastructure to make their journeys easier, such as ramps, lifts and provision of wheelchairs at airports.

However, while many physically disabled passengers say that there is still much to be done to improve their transport experiences, it could be argued that their needs are better catered for than for those passengers who suffer from hidden disabilities.

This article will be focusing particularly on challenges faced by travellers with autism, as well as the wider issues of challenges faced by airline passengers with hidden disabilities and what can be done to assist them. In researching this article, I have had the assistance of my daughter Jennifer who is autistic and has the comfort of an emotional support dog.

One of the main issues faced by hidden disability (also known as neurodivergent) travellers, says Jennifer, is that – at the risk of stating the obvious – their disabilities are hidden. While it should be obvious to onlookers that someone in a wheelchair is physically disabled and needs special treatment, the same cannot be said of someone with a hidden disability.

Autism is a mental condition which can affect how people experience the world. It can affect all five senses, including under and oversensitivity to noise, light and scent which would not normally be noticeable to neurotypical people. According to the British Medical Association, an estimated 700,000 people in the UK have a diagnosis of autism.

Special lanyards or wristbands allow staff to discreetly identify travellers with autism or other hidden disabilities. The green sunflower lanyard is an internationally recognised symbol for hidden disabilities. RNIB

Special lanyards or wristbands allow staff to discreetly identify travellers with autism or other hidden disabilities. The green sunflower lanyard is an internationally recognised symbol for hidden disabilities. RNIB

However, Jennifer explains, every autistic person is different, so that problems faced by one individual may not be the same as those experienced by another. In her case, she tells me, her five senses are dialled up to much higher levels. This means that what some people consider to be acceptable levels of noise are deafening to many autistic people. The same phenomenon also occurs for other senses, such as touch and taste. A fear of overcrowding is also a problem.

Another factor is that of order. Autistic people, Jennifer states, like to know what to expect in advance. Unexpected events or sudden changes of plan are bad news. Autistic travellers also like to feel secure, yet at the same time also do not like being confined.

If the levels of stress and anxiety become too much, it can impact on the individual’s ability to communicate effectively. One issue experienced by autistic people subjected to too much stress is to experience a ‘meltdown’ in which they may become non-verbal and are unable to communicate or receive communications. All forms of social communication become difficult and eye contact can be painful and confusing. In some cases, people may become aggressive due to feeling afraid for their safety.

Left: Signs showing that travellers with autism or other hidden disabilities are assisted and catered for. Middle: Belfast City Airport provides hidden disability lanyards. Right: Airport special assistance desk.

Left: Signs showing that travellers with autism or other hidden disabilities are assisted and catered for. Middle: Belfast City Airport provides hidden disability lanyards. Right: Airport special assistance desk.

So, how does this relate to air travel? In N 2016 the CAA published guidance for airports on providing assistance to people with hidden disabilities (CAP14111), based on the minimum compliance standards under Regulation EC1107/2006 (which applies both to the EU and to the UK). This has since been supplemented with additional guidance for airlines flying from the UK and for flights to the UK on an EU- registered airline. Under the regulations, an airline must not refuse travel on the grounds of disability or reduced mobility unless it must do so to meet applicable safety requirements.

The CAA has created requirements following the guidelines which it says are focused on providing practical benefit to passengers, airlines and airports. The US also has regulations regarding hidden disabilities in the form of the Air Carrier Access Act (ACAA) Title 14 which prohibits commercial airlines from discriminating against passengers with disabilities.

Now, let’s look at the travel experience from the point of view of an autistic passenger.

As everyone knows, the experience of travelling through an airport can be a stressful enough experience for neurotypical passengers – with queues, crowds, noise, security checks, delayed or cancelled flights – and all that is before you even get aboard an aircraft. Having a hidden disability is stressful enough at the best of times but is even worse when travelling. For people with autism, air travel can be a confusing and even frightening experience.

As everyone knows, the experience of travelling through an airport can be a stressful enough experience for neurotypical passengers – with queues, crowds, noise, security checks, delayed or cancelled flights – and all that is before you even get aboard an aircraft. Having a hidden disability is stressful enough at the best of times but is even worse when travelling. For people with autism, air travel can be a confusing and even frightening experience.

Many airports provide special lanyards or wristbands which allow staff to discreetly identify travellers with autism or other hidden disabilities. Autistics often wear a sunflower lanyard which is an internationally recognised symbol for hidden disabilities. Airport staff have been trained to recognise the lanyards and to give individuals with hidden disabilities the option to identify themselves as needing assistance.

Some airports also have special ‘quiet routes’ to enable hidden disabled passengers to avoid crowds, as well as quiet rooms. A number of airports offer the option for families to go to the airport in advance of their flight in order to carry out a ‘practice run’ of the security process and mock boarding, to get a deeper understanding and familiarisation of the experience before travelling.

In researching this article, Jennifer and I looked at the advice given by airports and airlines aimed at autistic travellers and found that, while they were a move in the right direction, there were still some issues which needed resolving. The first of these is that the assistance offered by airports appears to be mostly aimed at children and does not acknowledge that adults can have autism too. It also assumes that the autistic passenger is travelling accompanied.

There could also be issues with going through security checks, as many autistic people are hypersensitive to the sound of alarms or to touch if searched. While welcoming the offer of going through airport security in less crowded lanes, Jennifer was less sure about the autism-friendly quiet rooms. In practice, these might not be as quiet or as uncrowded as desired. She was also concerned about a lack of windows.

There could also be issues with going through security checks, as many autistic people are hypersensitive to the sound of alarms or to touch if searched. While welcoming the offer of going through airport security in less crowded lanes, Jennifer was less sure about the autism-friendly quiet rooms. In practice, these might not be as quiet or as uncrowded as desired. She was also concerned about a lack of windows.

While the idea of advance familiarisation visits is a good one, it is not always practical if you do not live anywhere near an airport. The advance visit would also have to be restricted to the landside part of the airport and so could not provide any idea of what to expect in a security queue or departure lounge.

Another issue was what to do in the event of flight delays or cancellations at the airport, as some autistic people find it difficult to sit still for long periods of time. Autistic people can become more anxious in situations where events do not follow a set schedule. Jennifer was also concerned about whether there were any provisions to assist autistic passengers in unexpected emergency events, such as an airport evacuation.

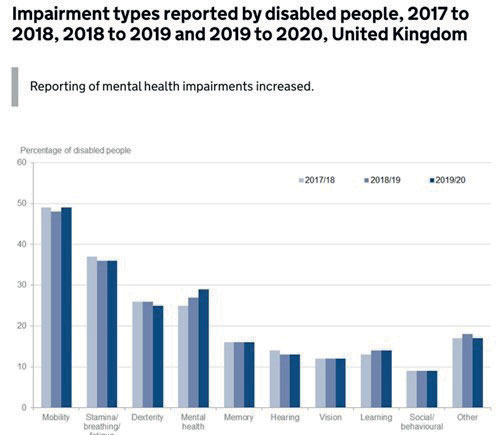

There has been an increase in mental health issues reported by disabled people 2017- 2020. 2021 Family Resources Survey There has been an increase in mental health issues reported by disabled people 2017- 2020. 2021 Family Resources Survey |

A number of airports have therapy dogs to help passengers before they fly, such as Minneapolis-St Paul (MSP) Animal Ambassadors which brings a number of dogs to the airport. Airport Foundation MSP A number of airports have therapy dogs to help passengers before they fly, such as Minneapolis-St Paul (MSP) Animal Ambassadors which brings a number of dogs to the airport. Airport Foundation MSP |

Once they have arrived at the departure gate, autistics now face a new set of challenges. Under the CAA regulations, carriers must make all ‘reasonable efforts to arrange seating to meet the needs of individuals with disability or reduced mobility on request, subject to safety requirements and availability’. It is usual practice for disabled passengers and those with reduced mobility to be boarded first.

While agreeing that this is a helpful practice, Jennifer observed that there could be issues from other passengers who might object to seeing someone who – from their perception – appears to be perfectly fit and healthy, being given priority to board an aircraft before them. There could also be anxiety problems if autistic passengers are left waiting in unfamiliar surroundings, such as on an airbridge.

Where best to sit aboard the aircraft is also a problem. Jennifer explained how there was a conflict between two requirements of some autistics – one being a dislike of enclosed spaces and another of being always close to an exit.

Being seated at a window seat is good because there is a view out which will reduce feelings of claustrophobia. However, if the adjoining seats are occupied by strangers, this will increase feelings of anxiety over feeling too enclosed.

Window seats may be best for passengers who may be irritated about having to constantly get up or maybe worried about sitting next to a stranger, whereas an aisle seat would be better for passengers who may feel enclosed and enjoy a walk around the aircraft or need to use the toilet regularly.

All of which brings us to the subject of dogs. While everyone is probably familiar with how guide dogs can assist blind people, what may be less well known is the work of other assistance dogs which are trained to support disabled people and people with medical conditions. Many people who suffer from a variety of illnesses, including mild to severe depression, phobias, PTSD, anxiety and panic attacks have found that companionship of an emotional support animal alleviates symptoms.

A service dog. Beverly Hills Veterinary

A service dog. Beverly Hills Veterinary

A few words of clarification may be useful here regarding the definitions between the two different types of dogs used to assist autistic and other neurodiverse people.

Service dogs: dogs trained to perform tasks for the benefit of an individual with a disability.

Also referred to as assistance or support dogs. Emotional support animals (ESAs): dogs and other animals which are not trained but which provide emotional support and alleviate symptoms of anxiety and stress. Also referred to as comfort or therapy animals.

Most airlines allow passengers to take assistance dogs to accompany disabled passengers in aircraft cabins, provided the dogs have been properly trained, can be relied upon to behave well and conform to local health rules.

However, there are some restrictions on ultra-long-haul flights. The rules as to whether to allow non-trained ESAs into aircraft cabins depends on the policy of individual airlines. Up to the end of 2020, US airlines were obliged to allow passengers to take comfort animals with them for free on the aircraft.

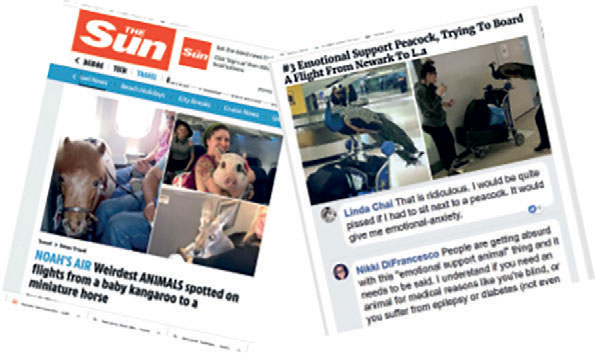

However, some passengers took a somewhat broad definition of what constituted as a comfort animal and the internet is full of stories about people trying to bring strange and unlikely animals with them on aircraft, including pigs, hamsters, monkeys, turkeys and even peacocks – some of which were refused entry onto aircraft and some of which caused trouble once they were aboard.

News stories about unusual emotional support animals like these do not help promote the welfare of any disabled passengers

News stories about unusual emotional support animals like these do not help promote the welfare of any disabled passengers

There were also cases of people with no disabilities, either physical or unseen, paying for fake certificates for ESAs in order to take their pets with them on flights for free.

Unfortunately, whether the value of some animals for emotional support was justified or not, the result led the US Department of Transportation to say that unusual animals on flights had ‘eroded the public trust in legitimate service animals’.

In December 2020 the US Department of Transportation announced a revision to the Air Carrier Access Act. As a result, the rules in the US were revised so that, from 11 January 2021, only service dogs will be permitted.

The decision was applauded by airlines, which had been trying for years to change the rule, as well as airline employee unions. The President of the US Association of Flight Attendants was quoted as saying: “The days of Noah’s Ark in the air are hopefully coming to an end.”

Another challenge facing autistic passengers is that there have been incidents in which, under stress, people with hidden disabilities have exhibited ‘challenging behaviour’ – which has led to the passenger being denied boarding or even the aircraft being diverted for an emergency landing. Such incidents have resulted in autistic passengers being regarded with suspicion but, as Jennifer reminded me, all autistic people are different.

On reviewing these regulations, Jennifer had a number of comments. On the subject of service animals, Jennifer welcomed the policy by the majority of airlines to allow trained dogs to accompany passengers with hidden disabilities. Turning to the subject of comfort animals, Jennifer felt that the decision not to allow them on board most aircraft was unfortunate. Having experienced the emotional benefits of having a comfort animal, Jennifer felt that airlines should be more open to allowing them to travel with their owners, provided that they could be proved to comply with basic behavioural standards.

Speaking as an autistic person, Jennifer was concerned that negative publicity from recent incidents in which autistics were restrained or removed from aircraft was damaging both to the public perception of autistic passengers and to the emotional wellbeing of all autistic passengers.

A fresh challenge for autistic travellers has been the additional health requirements for air travel as a result of Covid-19. Not only do passengers have to wear masks at airports and on aircraft but they also have to have pre and post-flight health checks and all the admin that goes with it.

Brisbane Airport non-verbal information lanyard. Brisbane Airport

Brisbane Airport non-verbal information lanyard. Brisbane Airport

This is not good news for neurodiverse passengers who would be subjected to additional stress of taking tests, sending off results and the uncertainty of whether the results with be positive or negative. The requirement to wear masks will also pose problems, as many autistics (Jennifer included) have a medical exemption from wearing them but may be forced to wear them in order to travel.

In conclusion, there are still many challenges to o be overcome before autistic passengers can be comfortable in flying. One of the major issues is a lack of public awareness of how challenging autistics can find the air travel experience, both from the general public and from airport or airline staff who are not aware of the personal challenges involved.

There is also not yet a joined-up end-to-end approach to supporting passengers with hidden disabilities across different airlines and airports around the world. Autistics who may be recognised and supported at one airport may not find that help at another. There are also discrepancies between different carriers over the carriage of comfort animals.

The problem has been recognised by the International Air Transport Authority (IATA) which is calling for a joint government and industry approach that meets the needs of passengers with disabilities while ensuring efficient and safe air transport. Working with the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), IATA is campaigning with states to closely involve the airline industry in the inclusion of the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UN CRPD) into national aviation legislation and policies related to accessible air transport.

In February 2021 IATA published the first edition of the IATA Passenger Accessibility Operations Manual (IPAOM) which provides guidance to support airlines in assisting passengers with disabilities, with the aim of delivering a smooth and dignified travel experience throughout their entire journey.

The ethical argument is clear – everyone, regardless of whether they are disabled or not, should have the same rights to enjoy travelling by air. If regulations and policies regarding passengers with hidden disabilities are standardised so that autistic and other neurodiverse passengers gain equal access to air travel and feel encouraged and welcomed, then there is an additional potential market to be realised by airlines and airports.