SPACEFLIGHT UK military space strategy

Defending space

TIM ROBINSON FRAeS reports on the release of the highly-anticipated UK Defence Space Strategy.

RAF Fylingdales helps provide space domain awareness (SDA) for the UK and allies.

RAF Fylingdales helps provide space domain awareness (SDA) for the UK and allies.

February this year saw the long-awaited UK Defence Space Strategy released by the Ministry of Defence (MoD), a document that has seemingly been lost in space since 2018 when it was first announced by the then Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson MP.

Since then there have been two more Defence Secretaries, the UK Integrated Defence and Security Review and a National Space Strategy, as well as the stand-up of the UK’s Space Command in July 2021 – in addition to the wider space sector accelerating even further with the rollout of mega-constellations and private human spaceflight.

Crucially, from a defence/security point of view, the past four years have seen no let-up in nefarious activity in space, from rendezvous and proximity operations to kinetic attacks that have created hazardous space debris. Only late last year, a Russian anti-satellite missile test put the International Space Station (ISS) in peril – an action that could have spectacularly backfired on its own cosmonauts on the station, as well as the other astronauts on board.

In parallel, and perhaps unappreciated by the majority of the public, the global Covid pandemic of the past two years has also increased modern society’s dependence on space-based critical infrastructure – as supply chains have responded to the increase in home working and the demand for GPS-tracked goods, e-commerce and home deliveries went through the roof.

So what is the Defence Space Strategy (DSS) and what does it seek to do?

In short, with the UK having announced it intends to become a leading space power, the DSS now outlines how it will operationalise the space domain, the priorities that will receive funding and informs international partners and industry on how the UK intends to deliver these over the next few years.

Says Defence Secretary Ben Wallace MP: “This is a pivotal moment for UK Defence as it seeks to operationalise the space domain at pace”.

The DSS allocates £1.4bn of funding over the next decade, with investments in new space R&D and technology programmes and capabilities – on top of the £5bn already earmarked for the UK’s Skynet military satellite communications system.

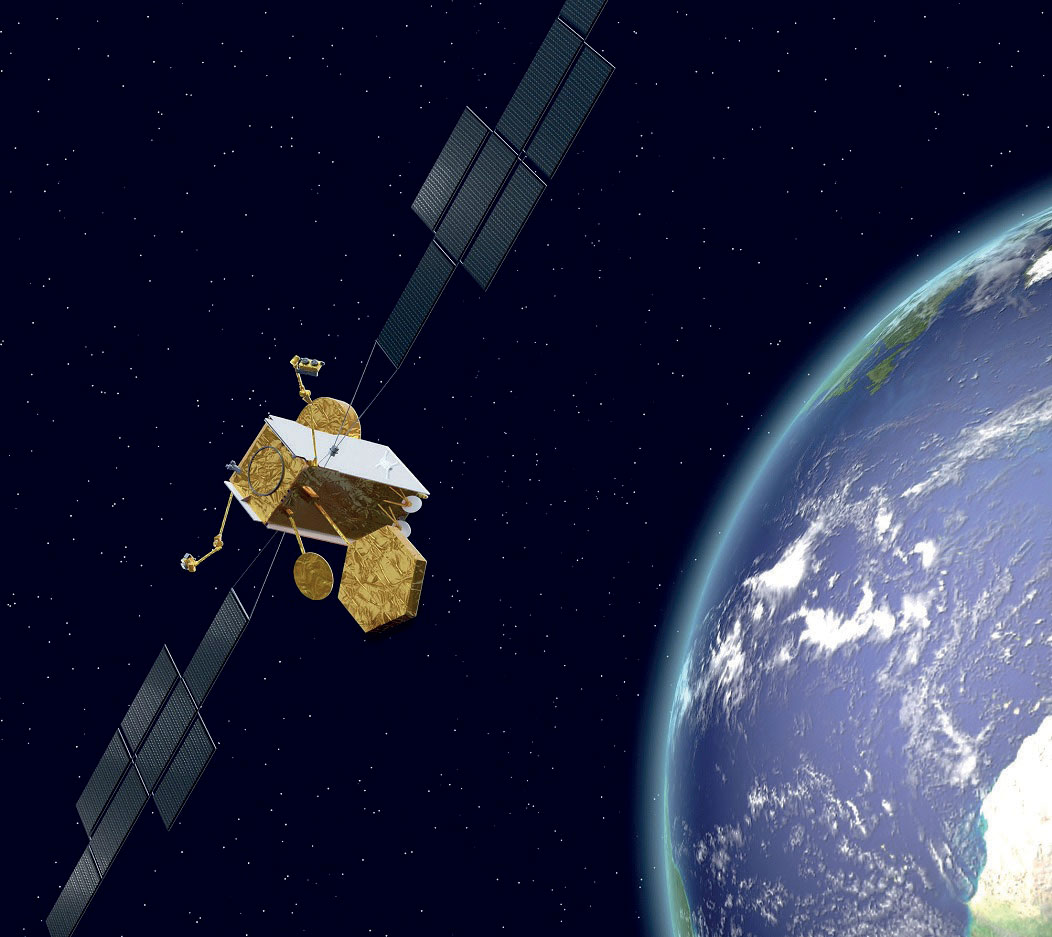

The Skynet 6A satellite. MoD

The Skynet 6A satellite. MoD

These include a further £60m in Skynet and SATCOM capabilities, £85m in Space Domain Awareness (SDA), a critical capability in understanding, classifying and attributing objects in orbit.

Meanwhile, the bulk of the £1.4bn, (some £970m) will go towards generating a ‘suite of on-orbit sensors, expanding the digital backbone into space and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) constellations, all underpinned by a novel and secure ground architecture’. This multi-satellite ISR capability will be known as ISTARI – the wizards from Tolkien’s Middle Earth.

However, SDA and subsequent Space Traffic Management (see below) cannot be a purely national initiative but calls for international engagement guided by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), not mentioned in the strategy, and routine access to data provided by the Lockheed Martin Space Fence to identify and alert satellite owners of the imminent risks to other satellites.

The strategy calls for the intention to “strengthen the resilience of the PNT (navigation) services on which our critical national infrastructure and economy depend”, although no specific funding has been identified. Indeed, this is most likely a sign that the UK is no longer able or willing to deliver on its original significant and potentially costly intention to find an alternative to the EU Galileo system, to which the UK had full protected access before leaving the EU. The alternative and less costly option selected is for the UK to beef-up the security of PNT data to which it has (free) access. A further report on UK PNT options is set to be released in the near future.

There is also more funding allocated to develop the space organisation and professionals needed, with £135m for Space Command & Control. This includes developing and enhancing UK Space Command and developing the SpOC (Space Operations Centre) with the aim of a combined civil/ military UK National Space Operations Centre – something that will be increasingly needed as the UK launches its own satellites from UK soil. A training needs analysis is also under way to help develop and grow the cadre of UK space professionals, including the potential establishment of a dedicated Space Academy.

One interesting aspect is the additional £145m investment in Space Control – or the ‘space warfare’ aspect that fills people’s imaginations and tabloid headline writers with visions of anti-satellite (ASAT) missiles or lasers. The truth is likely to be much more measured and non-kinetic, such as cyber, EW or potentially dazzling or blinding a hostile satellite sensors. These have all the benefits of disabling an enemy satellite (either temporarily or permanently) without the danger of creating deadly fragments of space debris that could threaten friendly satellites. A blinded satellite, too, would still be under operational control from the ground.

One change in the DSS is that the confusingly named MoD Artemis programme, which shared its name with NASA’s return to the Moon project, has now been ditched. Described as being successful, this has now been folded into Minerva, a four-year programme, which will develop a robust and secure space network, similar to the ‘Combat Cloud’ of datalinks and communications which will ‘autonomously collect, process and disseminate data from UK and allied space assets.’

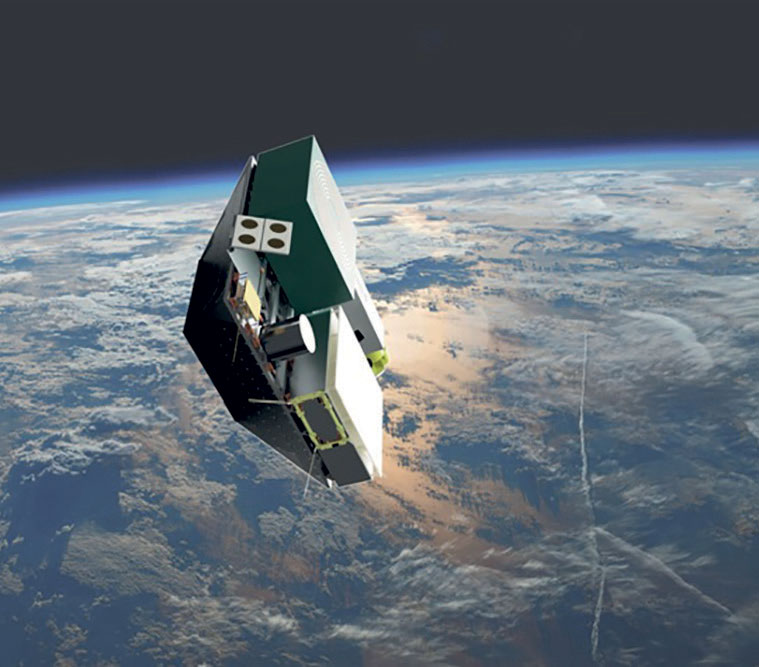

Titania is a laser communications satellite demonstrator. DSTL

Titania is a laser communications satellite demonstrator. DSTL

This will include not only space-to-ground but also space-to-space – which increases resilience and also allows quicker transmission of data and imagery without needing an ISR satellite to have line of sight to a ground station. Titania, meanwhile, is a laser communications satellite demonstrator, which not only offers high bandwidth but also makes interception or jamming of the signal extremely difficult.

Once proved, Minerva will form the network backbone of the larger ISTARI ISR satellite capability, which will see hyperspectral, SAR and other satellites capabilities combined together. ISTARI is also aimed to be compatible with US and allied space networks, allowing the UK to ‘plug in’ and share its data. The goal is to demonstrate an integrated system to Five Eyes partners by 2025 and satellites with advanced sensor capabilities to enter IOC in 2025 – only three years from now.

The ultimate vision, according to a senior RAF source, is the creation of a future space-to-ground network that, for example, could see a fleet of satellites monitor the North Atlantic for submarines. This information could then be passed on to long-endurance Protector drones, which could in turn cue P-8A Poseidon patrol aircraft – allowing for a persistent and seamless kill chain.

Ironically, the UK’s requirement to monitor and track maritime movements using dual-use systems could most likely be fulfilled by the UK rejoining the EU Copernicus mission, providing high-quality, high-volume data for monitoring climate change, as well as security-related issues. Apparently, UK negotiations with the EU on this subject have not come to a satisfactory outcome, either for the UK nor the EU.

While the DSS includes several investments in space technology, it also includes aspects of organisational and ‘soft power’ to enhance Britain’s space power. One of the aims, for example, is to grow a space cadre from this small nucleus to a larger community of military space professionals. To that end, a panel discussion at the launch at King’s College Freeman Air & Space Institute also saw an invite extended to academia and PhD students in particular to contribute to this.

Air traffic control allows the safe operation of metal tubes with hundreds of people on board travelling at high speed every day. Is a Space Traffic Control needed? NATS

Air traffic control allows the safe operation of metal tubes with hundreds of people on board travelling at high speed every day. Is a Space Traffic Control needed? NATS

In ‘soft power’ the UK has already been working hard at the UN level to gather diplomatic support in establishing a base level of international norms for outer space – that define nefarious and unsafe conduct and promote transparency. Having these norms agreed at the international level thus means that unsafe activity in orbit can be called out and responded to. This could potentially include terrestrial responses – eg sanctions on nations persisting in carrying out dangerous manoeuvres in space that threaten the common good. However, without a baseline of ‘normal activity’, it is thus difficult to generate an international consensus.

Further in the future, these norms may evolve into a Space Traffic Control or a ‘Space ICAO’ that could issue Space NOTAMs, warnings about exercises, proximity operations, and ‘rules of the road’ – much like civil aviation is governed today where agreed international regulations have made passenger flight incredibly safe. UK Director Space, AVM Harv Smyth draws a parallel with civil aviation, noting that 100 years ago, it would have been inconceivable* that jet airliners flying at 500mph, with 300 people on board would be landing at Heathrow routinely and safely thanks to one hundred years of rules, standards and regulations that have evolved. Space, then is likely to head the same way.

One big question, of course, is whether the UK can afford to invest fully in this new domain, even as some of its conventional military forces are arguably being hollowed out – see for example the poor state of the British Army’s tank arm. The situation in Ukraine is a case in point – a myriad of military and commercial satellites are recording the Russian build-up of armoured forces on the border in stunning levels of detail but, should things escalate, the PBI (Poor Bloody Infantry) armed with an anti-tank launcher will be quickly overrun, no matter how impressive the resolution of sensors watching from orbit. Despite these concerns, there is optimism that the UK’s ambitions in military space are within financial reach.

Firstly – it is not attempting to replicate the entire massive spectrum of the US or Russian military space capabilities or build infrastructure that, in those nations case, dates from the early Cold War. Instead, the UK is seeking to invest in key areas that provide sovereign control, fill gaps not covered elsewhere, develop key technologies and offer most bang for the buck (Rogers).

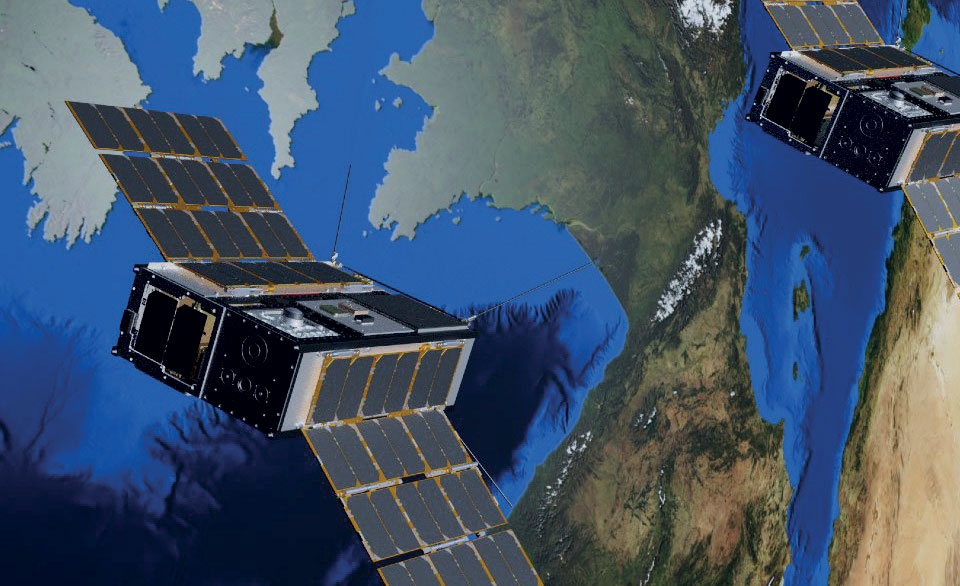

Built by In-Space Missions, DSTL’s shoebox-sized Prometheus 2 CubeSats will pack a number of advanced sensors and capabilities in a tiny package. DSTL

Built by In-Space Missions, DSTL’s shoebox-sized Prometheus 2 CubeSats will pack a number of advanced sensors and capabilities in a tiny package. DSTL

Second, is that ‘dual use’ satellite technology offers a way in which satellites, payloads or even sensors could be shared. Imagery satellites, for example, could be tasked with farming, agriculture or urban planning but revert to military control in the event of a crisis. In this way, other departments and stakeholders could help share budgets and investment. Indeed ‘dual use’ is nothing new, says AVM Smyth, who points out that, since its inception, the humble telephone has been a ‘dual use’ technology from chatting with family to co-ordinating a military operation.

Today smartphones can be used for TikTok videos or to trigger an IED. On a panel at the launch of the DSS, Rebecca Evernden, Director Space, BEIS said of the opportunities in dual use: “that is where the UK could get really ahead”.

Third, is that the costs of space technology and access to space are falling dramatically. Britain itself was one of the pioneers in smallsats and remains a key player in nano and microsat technology, thanks to companies like SSTL. For example, one project funded by DSS is In-Space Mission’s Prometheus 2 demonstrator which will pack optical, radios and GPS receivers in a spacecraft the size of a shoebox. Nanosatellites built using COTS components and technology are now within the budget of high schools and colleges, never mind a country like the UK.

The cost of getting to space is also falling rapidly as the launch industry scrambles to compete with the juggernaut that is SpaceX. From $54,500 per kg into orbit using the Space Shuttle, SpaceX now offers a highly affordable $2,700 per kg using its Falcon 9 rocket. Further in the future, SpaceX’s larger Starship goal is to bring the cost down to a staggering $10 per kg – a price that could have transformational implications that we can only glimpse at today and usher in a new off-planet industrial revolution.

Put together, these factors mean that for a new space power attempting to catch up with others, the UK’s money will go far further than in previous decades.

The limited government funding allocated to implementation of the strategy is (partly) justified at the beginning of the document: “Space-related activity was once solely the preserve of governments... Today though, investment is driven by private investors and the UK space industry-primary income is from commercial ventures....”. This has clearly led to the UK government’s choice to make only a modest new allocation to implement the strategy, namely an additional £1.4bn over 10 years (=£140m pa). The £5bn also cited is not new and is already allocated to Skynet over the next 10 years.

The same approach (limited government funding) was taken for the (civil) UK Space Strategy and demonstrates a lack of awareness of the high overall returns to the UK economy from public investment in space activities. Based on London Economics data, the average return for every £1 invested in space-related activities is £10, rising to £17 (specifically related to Harwell).

This also shows that the UK has clearly no intention to invest the same level of public funding in implementation of its space strategy that France, its most important European defence partner, has done. Even leveraging the above factors then, will the £1.4bn be enough?

Overall then, the DSS represents a welcome way forward as the UK aims to deliver its ambitions to become a more muscular and active space player – even if it has taken four years to see the light of day in what is an extremely fast-moving sector. Crucially, it sets out the UK’s stall for industry and allies around the world to see and to identify opportunities to collaborate and co-operate and reaffirms Britain’s aim to become a ‘meaningful space actor’ and partner with friends and allies. Additionally, while the DSS has been floating in limbo, much work, such as Artemis, the RAF’s Carbonite 2 satellite demonstrator, has actually been going on in the background – explaining the aggressive timescales that will see ISTARI integrated with Five Eyes allies by 2025.

The Strategy addresses the UK’s high-level defence objectives and identifies the steps to be taken in order to understand how these high-level objectives are to be met, namely by defining the requirements and investigating the different options for implementation. The funding, while perhaps sufficient to allow studies and technology demonstrations, is unfortunately insufficient to cover the full implementation of the selected solutions and their subsequent operation.

Having finally been published, the DSS is now likely to take centre stage at the MoD’s Defence Space Conference in May where undoubtedly more information on technology, programmes, opportunities and the wider strategic environment of military space will be discussed.

* But not fully inconceivable. In 1921 a report by the RAeS into Cross-Channel aerial transport suggested air traffic control and wireless communication, as the number of passenger airliner flights between London and Paris increased.