Book Reviews

By David J Shayler and Colin Burgess

Springer Praxis Books, 2021, 624pp, £24.99.

The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe’s award-winning 1979 novel, covered the selection and spaceflights of the Mercury 7, the US astronauts of the 1950s, and was adapted for screens big and small (1983 and 2020 respectively). This book focuses on the 1970s and new crewmen – and women – for the first reusable spaceplane, the Space Shuttle. With the tenth anniversary of the shuttle’s final landing behind us, the book feels appropriately timed. The authors are experienced spaceflight researchers, having written or co-written nearly 50 texts. They’ve covered the selection of the first seven astronaut groups and this book addresses NASA’s 1978 selection of the Group 8 astronauts, nicknamed the ‘Thirty-Five New Guys’ (TFNG).

Sally Ride, mission specialist on STS-7, monitors control panels from the pilot’s chair on the flight deck of the space shuttle Challenger in June 1983. NASA.

Sally Ride, mission specialist on STS-7, monitors control panels from the pilot’s chair on the flight deck of the space shuttle Challenger in June 1983. NASA.

Like their predecessors, many applicants were pilots, continuing the aviation legacy begun by Wilbur and Orville decades before; the Wright Stuff as well as the Right Stuff. There wasn’t just a change of spacecraft but of culture. The authors describe NASA’s admirable drive to attract minorities and women into space. Readers shocked by the casually sexist comments of some (the authors even name some Mercury-era heroes here) will be particularly gratified by the account of an unnamed NASA loud-mouth ridiculing the future astronaut Sally Ride, who promptly thrashed him in a racquetball game.

Equality issues, though mentioned in the book, don’t dominate it. Nonetheless, some readers may feel that the authors don’t go far enough – there is no mention of Sally Ride being the first LGBTQ individual in space. However, any criticism of bowing to political correctness is unfounded: diversity is not merely apparent in those selected but also in those who were not. Refreshingly, the authors also interviewed those who either were rejected or chose not to pursue their applications further.

The interviews also lend the astronauts an endearing – even inspiring – ordinariness. Many RAeS readers may recognise themselves in the candidates who were selected for the shuttle. Many were also parents with household chores to catch up on, while needing to – like many career-changers – find a new home. However, astronauts are also civil servants; the account of urban house-hunting is particularly sobering, as the future spacefarers struggled to find affordable Houston homes on their government salaries.

After the successful flight of the shuttle Columbia on STS-1, missions saw a mix of Apollo veterans and TFNGs enter orbit, where they carried out experiments, spacewalked and launched satellites. The busiest year, 1985, saw nine missions, which was far short of the intended fortnightly launch rate. Crews were now a multi-ethnic mix of civilians and military personnel, sometimes with ESA astronauts, and even (controversially) politicians on board.

Sally Ride, the first US woman in orbit, launched on STS-7 before a half-million-strong crowd. Yet any accusations of NASA’s wokeism remain meaningless, everyone was subjected to the same risks, as the Challenger disaster in 1986 tragically showed.

Four of the seven fatalities were from the TFNG (a further six TFNG later left NASA). Complacency was NASA’s biggest problem, which is rightly criticised by the authors, and led to the ‘frightening close call’ on STS-27 in 1988.

Material falling from the boosters damaged the shuttle Atlantis during launch; the crew feared that the re-entry would incinerate them. TFNG Mike Mullane was on board, and readers of his memoir Riding Rockets know that he lived to tell the tale. The briefer tale written here is equally gripping, though the damaged Atlantis landed safely. Many readers would agree with the author’s assertion that NASA’s laxness would destroy Columbia in 2003.

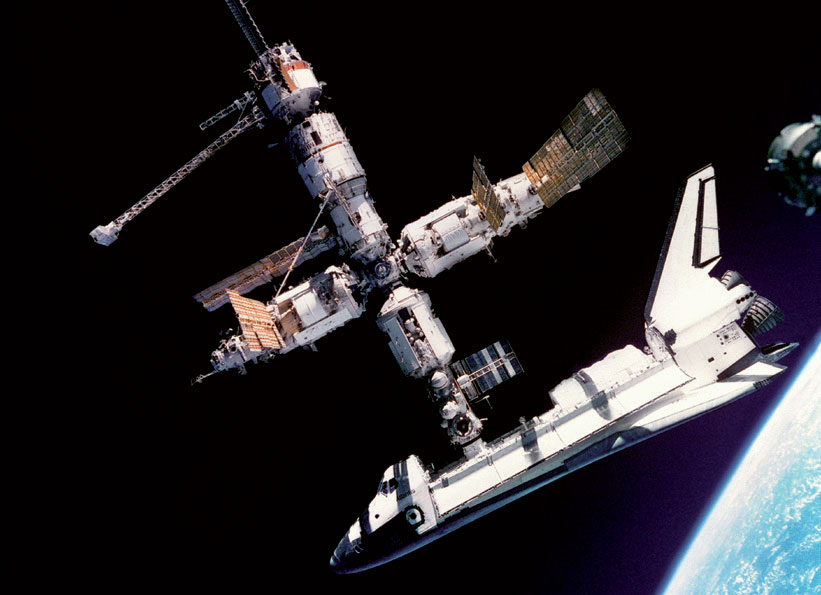

This view of the space shuttle Atlantis still connected to Russia’s Mir Space Station was photographed by the Mir-19 crew on 4 July 1995. The Soyuz spacecraft was temporarily undocked from the cluster of Mir elements to perform a brief fly-around. NASA.

This view of the space shuttle Atlantis still connected to Russia’s Mir Space Station was photographed by the Mir-19 crew on 4 July 1995. The Soyuz spacecraft was temporarily undocked from the cluster of Mir elements to perform a brief fly-around. NASA.

The major highlight of the 1990s were the Shuttle-Mir missions. STS-63 in 1995 was the first shuttle mission to the Mir space station. The authors maintain the human touch: Norman Thagard was so bored on Mir that NASA Administrator Dan Goldin apologised for sending him there.

If moving to Houston was hard, moving to Russia for cosmonaut training was harder; NASA struggled to find candidates for Shuttle-Mir flights. Shannon Lucid flew to Mir and read the novel she’d been given by her daughter but didn’t have its sequel (‘Could I dash out to the bookstore? No.’) She spent a total of 223 days in space and helped conclude the shuttle programme in 2011, talking the crew down as capsule communicator on STS-135.

By concentrating on a group of astronauts, many missions inevitably receive only cursory treatment. Yet the authors cram much into 600 meticulously researched pages (notwithstanding gaps in NASA’s archives).

By concentrating on a group of astronauts, many missions inevitably receive only cursory treatment. Yet the authors cram much into 600 meticulously researched pages (notwithstanding gaps in NASA’s archives).

They present not merely astronaut selection but also a history of the early shuttle programme. It is a mix of reference work (reminiscent of the 1990s Space Year books or Jane’s) and historical account.

Sometimes it is unclear which approach the authors’ favour; the lists and tables will help researchers and professionals seeking mission data but may disappoint fans of prose.