“ …This is certainly enough to place it within the very highest reaches of important scientific instruments and tools developed over the entire length of human history,”(1)) noted the leading aviation historian Richard P Hallion.

What is being described is the construction in 1871 – 150 years ago – of the world’s first wind tunnel under the auspices of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain.

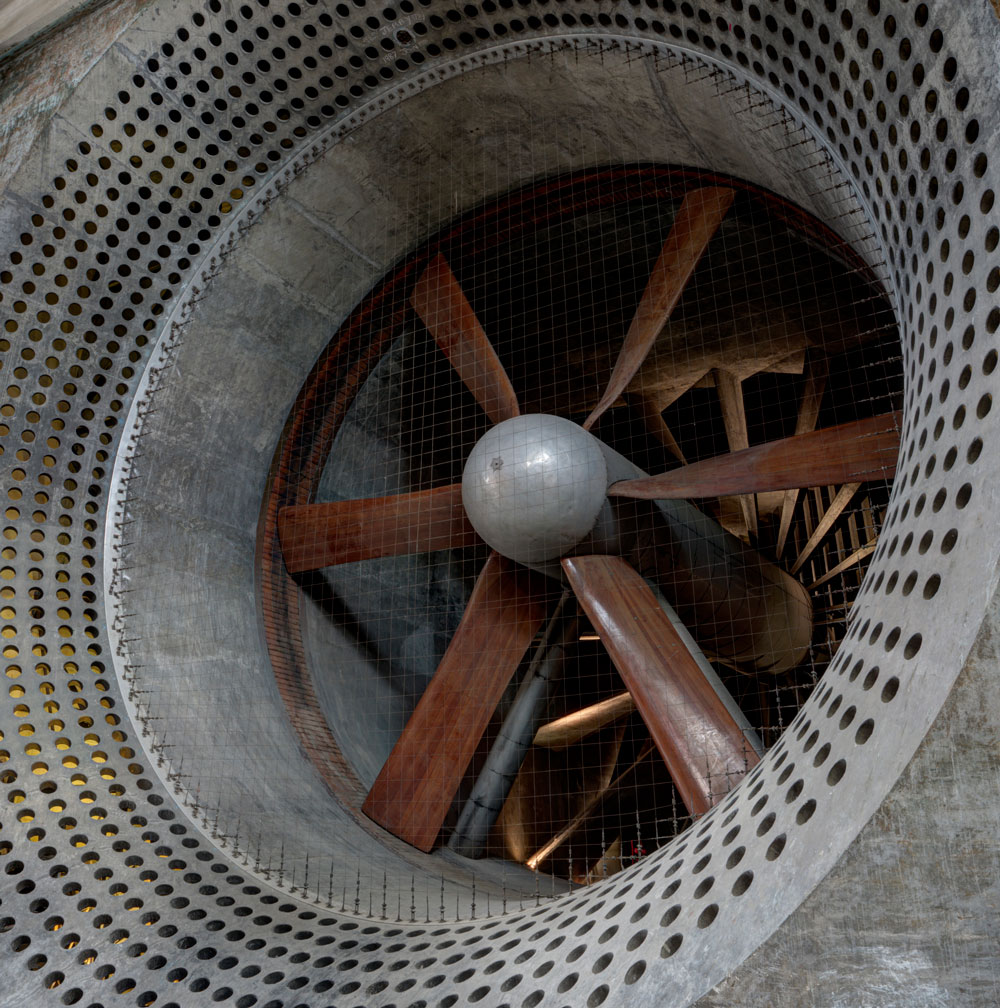

The main wind turbine fan in building Q121, part of the long retired wind tunnels in Farnborough, Hampshire, UK. Wambampram

The main wind turbine fan in building Q121, part of the long retired wind tunnels in Farnborough, Hampshire, UK. Wambampram

The tunnel was designed by Francis Herbert Wenham (1824–1908), one of the most influential figures in the pre-Wright era of aeronautics who conducted extensive studies of cambered wings and aspect ratios, and had delivered the first lecture to the Society entitled ‘Aerial Locomotion’ on 27 June 1866. In the Society’s Council minutes, dated 13 July 1870, it was reported that Wenham was among those appointed to “… a Committee for experimental purposes”. At the Council’s meeting of 3 July 1871, the Experimental Committee reported that it: “… had determined upon an Instrument designed by Mr. Wenham for experimenting with a view of discovering the relations existing between velocity and pressure at various angles”.

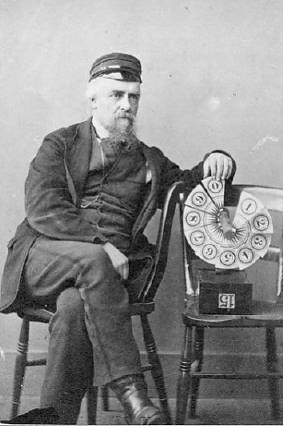

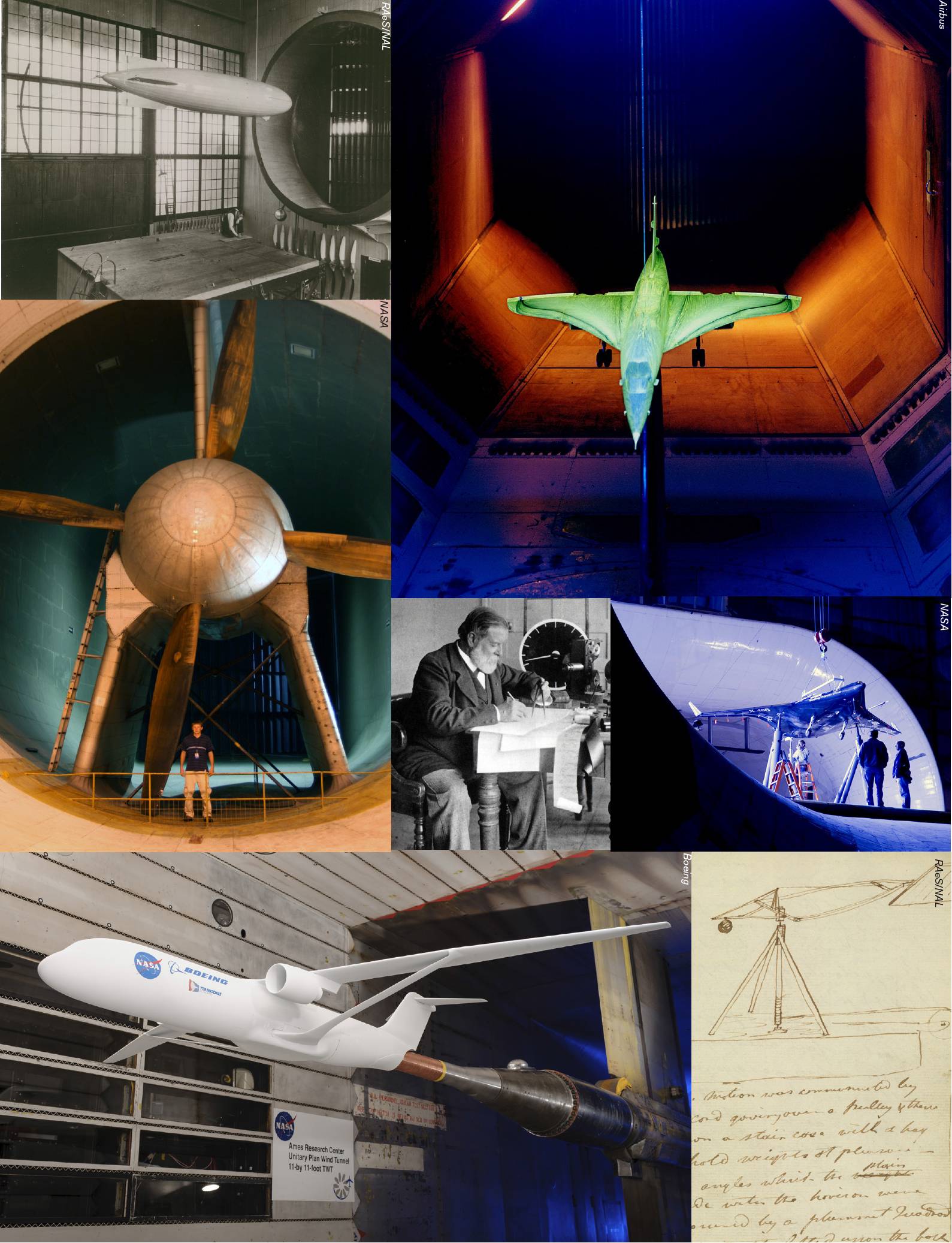

Francis Herbert Wenham. RAeS/NAL

Francis Herbert Wenham. RAeS/NAL

It was settled that the ‘Instrument’ which was to be submitted to ‘the requisite test with a fanblower’ was to be constructed by an optical and physical instrument maker, John Browning at John Penn and Sons marine engineering works at Greenwich (a manufacturer of industrial ventilation fans) at a cost of ‘about £25’ (around £3,000 in current values). It was reported in the RAeS’ Council minutes, dated 5 February 1872, that the Experimental Committee had conducted ‘the first series of their labours (tests) … and were tabulating the results’, the first public exhibition of the ‘new machine … for measuring the relation between the velocity and pressure of the wind’(2) occurring at the Society’s General Meeting of Tuesday 18 April 1872 held at the Society of Arts.

At the meeting, Wenham described “how it acted as an ordinary anemometer, for ascertaining the direct force of the wind on a plane, when in a vertical direction to its surface” by using a series of ‘planes’ mounted on a horizontal arm which could be set at various inclinations and vibrate in response to blasts of air(3).

Two years later, at the Society’s General Meeting of Tuesday 15 May 1874, Thomas Moy reported that based on the “… valuable experiments …made at Messrs. Penn’s factory, at Greenwich … those experiments went far beyond his expectations in favour of aerial navigation, and gave upward pressures at small angles which were not expected from any existing theory.

From the data furnished by these experiments, Mr. Moy had constructed a diagram of curves for pressures at different angles, and at speeds varying from 10 to 40 miles an hour”(4).

Prior to the work of Wenham, the single most important aeronautical theoretician of his era was Sir George Cayley (1773–1857) who adapted the whirling arm first designed in 1746 by Benjamin Robins (and constructed by John Ellicott) for measuring air resistance to determine the influence of the angle of incidence on aerofoils. Wenham’s invention of the wind tunnel – and its facility to allow data to be gathered on wing shapes of varying thickness, length and aspect ratio – represented a step-change opening up new avenues for the study of aerodynamic phenomena.

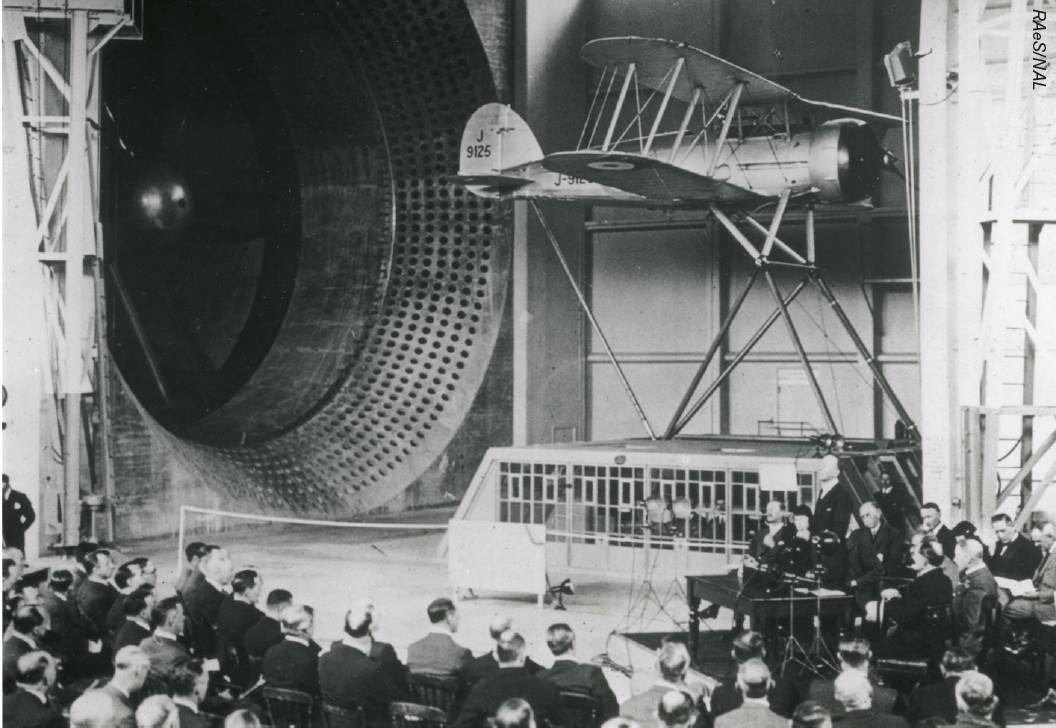

A Gloster SS19B, J9125, suspended in the same Farnborough 24ft wind tunnel when it was in active use. RAeS/NAL

A Gloster SS19B, J9125, suspended in the same Farnborough 24ft wind tunnel when it was in active use. RAeS/NAL

In Britain, aeronautical research – overseen by the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (ACA), formed by Lord Haldane in April 1909 – in the early decades of the 20th Century was centred around two sites – the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) at Teddington and the Royal Aircraft Factory / Establishment at Farnborough:

1903: Thomas Stanton constructs first wind tunnel at NPL.

1907: Construction of the first wind tunnel at the Balloon Factory, Farnborough, modelled on NPL design (over 20ft in length and 5ft square).

1917: Two 7ft tunnels constructed at Farnborough.

1919: Duplex wind tunnel built at NPL.

1933: Compressed air tunnel brought into use at the NPL.

1935: 24ft diameter tunnel opened at Farnborough.

The early evolution of the wind tunnel was pioneered in Europe, and during the following decade a number of significant developments occurred using wind tunnels including:

The early evolution of the wind tunnel was pioneered in Europe, and during the following decade a number of significant developments occurred using wind tunnels including:

1893: Ludwig Mach, son of the noted scientist Ernst Mach, built a 7in by 9¾in tunnel in Vienna specifically to photograph the motion of air, pioneering the use of photographic techniques to study airflow.

1894: A marine engineer Henrik Christian Vogt (1848–1928) studied pressure distribution around flat plates and various surfaces in a wind tunnel (40in long and 4½ x 9in in cross-section) constructed with the assistance of Johannes O. V. Irminger (1848–1938) at the Eastern Gas Works, Copenhagen.

1896: At the l’Éstablissement Central de l’Aérostation Militaire de Chalais-Meudon, Charles Renard (1847–1905) its Director built a 13ft 31" diameter wind tunnel to study the stability of airships.

1896–1897: Two small-scale wind tunnels were used by Poul la Cour (1846–1908), of Askov, Denmark, for windmill and wind turbine research. (The Danish Aerodynamic and Acoustic Wind Tunnel at DTU is named after him).

1896–1897: Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935) – later to be known as the ‘Father of Soviet Rocketry’ – as part of his research into designing a large metallic 200-passenger airship built a small wind tunnel, similar to Wenham’s design with a one-component balance to measure drag coefficients at Borovsk near Moscow. (In total from 1871 through 1915, 18 wind tunnels were constructed in Russia: eleven in Moscow, five in St Petersburg and two in Kaluga).

1899: In France, Étienne-Jules Marey (1830–1904) extended his studies of the flight of birds through rapid-sequence photographs to photographing the flow of air over various shaped bodies by means of smoke in a wind tunnel.

The following decades witnessed a major expansion of the development of wind tunnels in the United States, at both research establishments and the growing number of academic institutions offering aeronautical courses, including:

Replica of the Wright Brothers1913: Jerome Hunsaker, assisted by Edward P. Warner and Donald Wills Douglas, constructs wind tunnel based on NPL design at MIT.

Replica of the Wright Brothers1913: Jerome Hunsaker, assisted by Edward P. Warner and Donald Wills Douglas, constructs wind tunnel based on NPL design at MIT.

1918: The US Army constructed its first ever wind tunnel at McCook Field, Ohio, for high-speed testing of instruments and aerofoils.

1920: Operation began at Langley, VA, of the first NACA Wind Tunnel No.1.

1923: Variable Density Tunnel at Langley, VA. 1927: Propeller Research Tunnel (PRT) at Langley, VA, becomes operational.

1929: 5ft Vertical Wind Tunnel at Langley, VA, for investigations of the spinning characteristics of aircraft.

1930: 7ft by 10ft Atmospheric Wind Tunnel (AWT) at Langley, VA.

1931: The Langley Full-Scale Tunnel – 30ft by 6ft test section housed in a nine-storey building – was constructed by NACA for testing of full-scale aircraft. It was the largest wind tunnel in the world at the time and was to stay in operation until 4 September 2009.

1936: 8ft High Speed Tunnel (HST) at Langley, VA. 1938: 19ft Pressure Tunnel at Langley, VA (later adapted in the 1950s to become the 16ft Transonic Dynamics Tunnel (TDT)).

1938: Wright Brothers High Pressure Wind Tunnel – based on the original 1908 Ludwig Prandtl return flow design at Göttingen – inaugurated by the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aeronautics at MIT to simulate atmospheric conditions at various speeds/altitudes.

Also in 1871, in Russia, a wind tunnel and a three-component aerodynamic balance was designed and constructed by V A Pashkevich at the Mikhailov Artillery Academy, St. Petersburg(5).

The studies in 1884 of Horatio Frederick Phillips (1845–1926) to test the curvature and efficiency of various aerofoil sections in a wind tunnel of his own design – 6ft long and 17in square – encompassed the next milestone. In ‘Experiments with Currents of Air’, published in Engineering, 14 August 1885, Phillips’ tunnel was described as ‘… A rectangular trunk of wood … open at the front end, had attached to it at the back end an expanding delivery tube of sheet-iron’ through which air would be sucked through the entrance into the tunnel using a steam injection system to generate the airflow, effectively incorporating a diffuser into a wind tunnel: “The results obtained … are, we believe, the best hitherto recorded, and agree substantially with the highest results reached during the experiments made at Greenwich …”.

As Octave Chanute (1832-1910) noted in his book Progress in Flying Machines – a key work in the development of early aviation – Phillips’ experiments led “… to the inference that much greater supporting power is to be obtained from concavo-convex surfaces than from the flat planes which hitherto have been chiefly proposed for aeroplanes”(6).

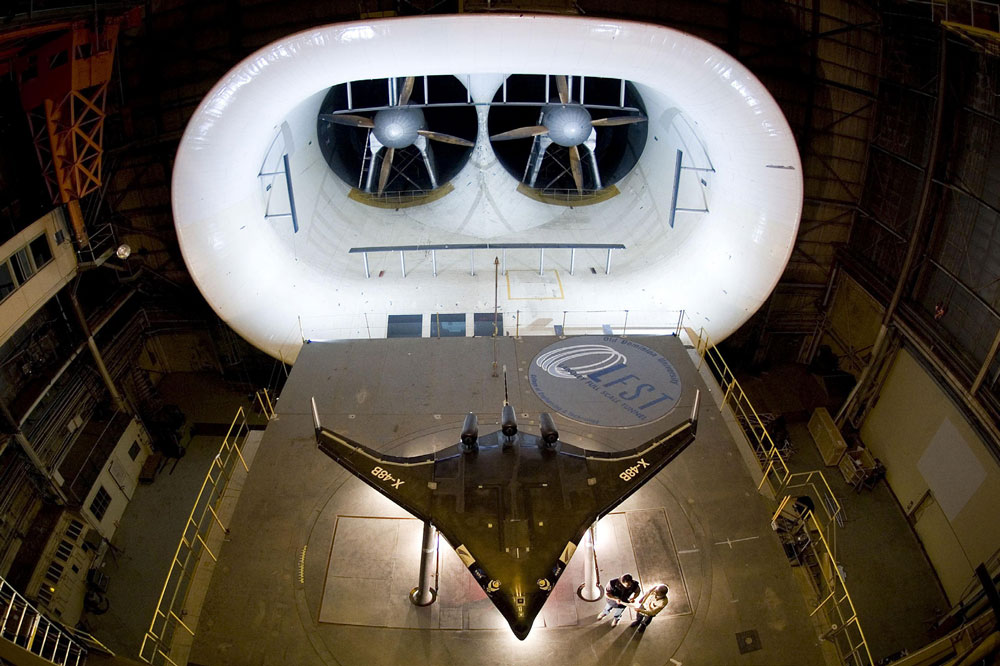

The X-48B, a flying scale model of a full-size blended wing body aircraft, in Langley

The X-48B, a flying scale model of a full-size blended wing body aircraft, in Langley

Back in Britain, from 1891–1894, Hiram Maxim (1840–1916) constructed in the grounds of Baldwyns Park, Kent, a huge biplane machine which made a short uncontrolled powered ‘hop’ flight in July 1894, just raising itself from the rails on which it ran. Initially, Maxim used data gathered from a huge whirling arm to develop his design but its limitations led him to a construct an ‘Apparatus for testing the lifting effect of aeroplanes and condensers in an air blast’ – a wooden box ‘ …12ft long and exactly 3ft square inside … connected … to a shorter box 4ft square’ – which incorporated two propellers placed vertically and horizontally and was powered by a 100hp steam engine. Maxim pioneered the use of wooden slats – placed in the tunnel horizontally, vertically, and diagonally – to straighten the air flow and thereby ‘ascertained the lifting effect … of various forms and at varying velocities of the wind, and, also, the resistance offered by various bodies driven through the air’(7).

Outside of Europe, in 1893, Professor William Charles Kernot (1845-1909) constructed the first wind tunnel – ‘blowing machine’ – in Australia at the University of Melbourne for the study of wind forces on buildings. In 1896, a mechanical engineering student Alfred J. Wells constructed the first wind tunnel in the United States – 30in2 – at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as part of his thesis.

German aviation laboratory, 1935. Bundesarchiv BildOn 17 December 1903, the Wright brothers – Wilbur (1867–1912) and Orville (1871–1948) – achieved at the four hills of Kill Devil, near the village of Kitty Hawk, NC – the world’s first piloted, sustained, controlled, powered flight in a heavier-than-air machine, with Orville Wright at the controls of the Wright Flyer. Their achievement was founded on years of wind tunnel experiments on wing surfaces of various configurations – and with their own kite and glider designs – and it was in their second tunnel (a wooden box 6ft long and 16in square inside) that over 200 model aerofoil configurations in more than one scale were tested, ‘a delicate instrument that would help the Wrights unlock the secrets of a wing’(8).

German aviation laboratory, 1935. Bundesarchiv BildOn 17 December 1903, the Wright brothers – Wilbur (1867–1912) and Orville (1871–1948) – achieved at the four hills of Kill Devil, near the village of Kitty Hawk, NC – the world’s first piloted, sustained, controlled, powered flight in a heavier-than-air machine, with Orville Wright at the controls of the Wright Flyer. Their achievement was founded on years of wind tunnel experiments on wing surfaces of various configurations – and with their own kite and glider designs – and it was in their second tunnel (a wooden box 6ft long and 16in square inside) that over 200 model aerofoil configurations in more than one scale were tested, ‘a delicate instrument that would help the Wrights unlock the secrets of a wing’(8).

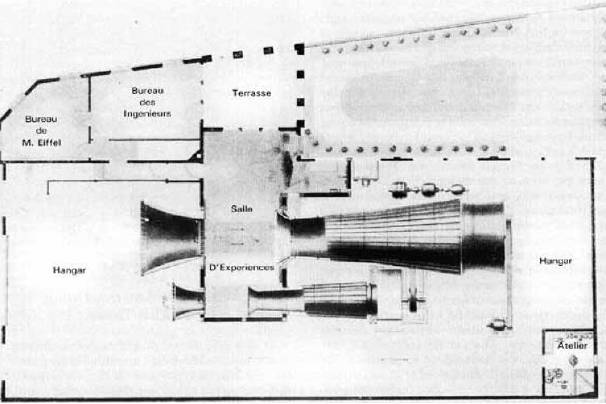

Europeans continued to lead the world in wind tunnel research through to the 1920s, the pioneering achievements of 19th Century individuals built upon by the funding of national governments and private individuals (such as Gustave Eiffel and Henri Deutsche de la Meurthe) to build major facilities.

Modelled on the European experience, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was established by the US Congress in March 1915, and the nation’s lack of wind tunnels – only two such facilities existed in the United States in 1910: the Wright Brothers’ tunnel in Dayton, OH, and Dr Albert Francis Zahm’s 1901 tunnel (40ft long wind tunnel, 6ft square in section, powered by a 12-horse-power electric fan) at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC – was a key concern.

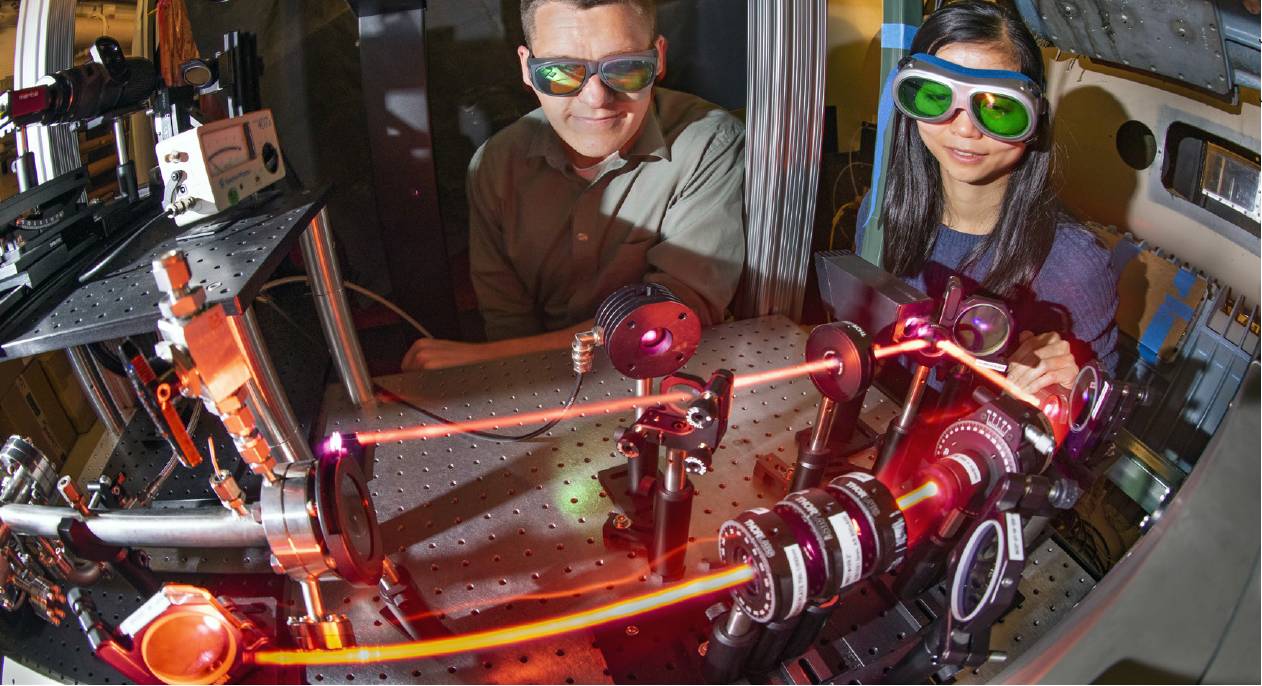

The hypersonic wind tunnel at the Sandia National Laboratories, US. Randy Montoya / Sandia National Laboratories

The hypersonic wind tunnel at the Sandia National Laboratories, US. Randy Montoya / Sandia National Laboratories

The 1930s witnessed the development of more aerodynamically efficient aircraft designs – a reflection of wind tunnel evolution, the streamlined design of the 1931 Douglas DC-1 airliner due to the extensive wind tunnel testing undertaken at the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology (GALCIT) in its 1929 10ft tunnel.

Research into high-speed aerodynamics (including swept and delta wings) also led to faster, more efficient designs. Jacob Ackeret (1898–1981) constructed during 1935–1936 the first wind tunnel capable of operating at Mach 2 at the Institüt fur Aerodynamik, Z›rich, Switzerland(9), much larger supersonic facilities being built at Peenemünde, Germany, related to the development of the A-4 / V-2 rockets.

In 1938 the first wind tunnel in China – the 15ft wind tunnel with interchangeable 18ft section for full-scale engine and airscrew tests of National Tsing Hua University in Peking – became operational. The Aeronautical Research Institute of Tokyo Imperial University had already incorporated a wind tunnel among its facilities when it opened in 1921.

From Francis Wenham’s pioneering design, the evolution of wind tunnels – which had transformed the fundamental understanding of aerodynamics and fluid dynamics – had truly become worldwide.

Clockwise from top left: A 1/40 scale model of the airship Akron in the Full-Scale Wind Tunnel; Airbus’ low-speed wind tunnel at Filton, Bristol, here carrying out tests on Concorde models in 1969; The triangular planform of the sub-scale X-48B Blended Wing Body prototype is evident as it awaits testing in the full-scale wind tunnel at NASA Langley; Sir George Cayley

Clockwise from top left: A 1/40 scale model of the airship Akron in the Full-Scale Wind Tunnel; Airbus’ low-speed wind tunnel at Filton, Bristol, here carrying out tests on Concorde models in 1969; The triangular planform of the sub-scale X-48B Blended Wing Body prototype is evident as it awaits testing in the full-scale wind tunnel at NASA Langley; Sir George Cayley

---

(1) Taking Flight: Inventing the Aerial Age from Antiquity through the First World War, Richard P. Hallion, New York, US, Oxford University Press, 2003, p 116.

(2) Seventh Annual Report of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain, 1872, p 5.

(3) Wenham’s tunnel was later described as “… a horizontal current was produced by a rotary fan, and the planes used were arranged so that they could be fixed at any required angle. The vertical force or lift, and the horizontal force or thrust, were ascertained by means of steelyards” ‘Experiments with Currents of Air’, Engineering, 14 August 1885, p 160.

(4) Ninth Annual Report of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain, 1874, p 6.

(5) The First Aerodynamic Balances in Russia, Paper presented at the 9th International Symposium on Strain Gauge Balances, A. R. Gorbushin and Valery S. Volobuyev, Seattle, 19-22 May 2014 ‘The Origin of Wind Tunnels in Russia’: Paper presented at ICAS 2016 30th Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences, DCC Daejeon, Korea, 25-30 September 2016.

(6) Progress in Flying Machines,The American Engineer and Railroad Journal, Octave Chanute, New York, US, 1894, p 157.

(7) Artificial and Natural Flight, Sir Hiram S. Maxim, Whitaker & Co, London, UK, 1908, pp 51-59.

(8) The Bishop’s Boys: a Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright, Tom Crouch, New York, US, W. H. Norton and Company, 1989, p 222. Wilbur Wright summarised his initial theories about “… the angle at which aeroplane and wind actually meet” in his first published paper ‘Angle of Incidence’, The Aeronautical Journal, July 1901 pp 47-49.

(9) The term ‘Mach number’ was introduced by Ackeret in his inaugural lecture at Federal Institute of Technology (ETH – Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule), Zurich, on 4 May 1929.