SPACEFLIGHT A preview of 2021 missions

Spaceflight in 2021 - a look ahead

The RAeS SPACE SPECIALIST GROUP looks ahead to the most significant crewed and uncrewed missions and spaceflight news for 2021.

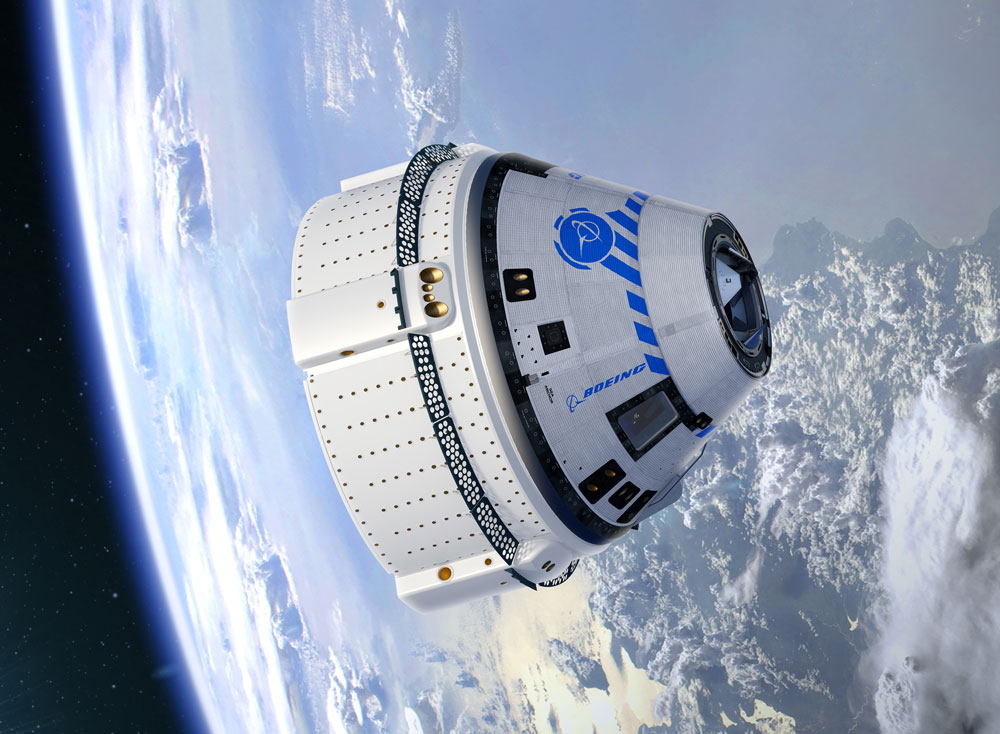

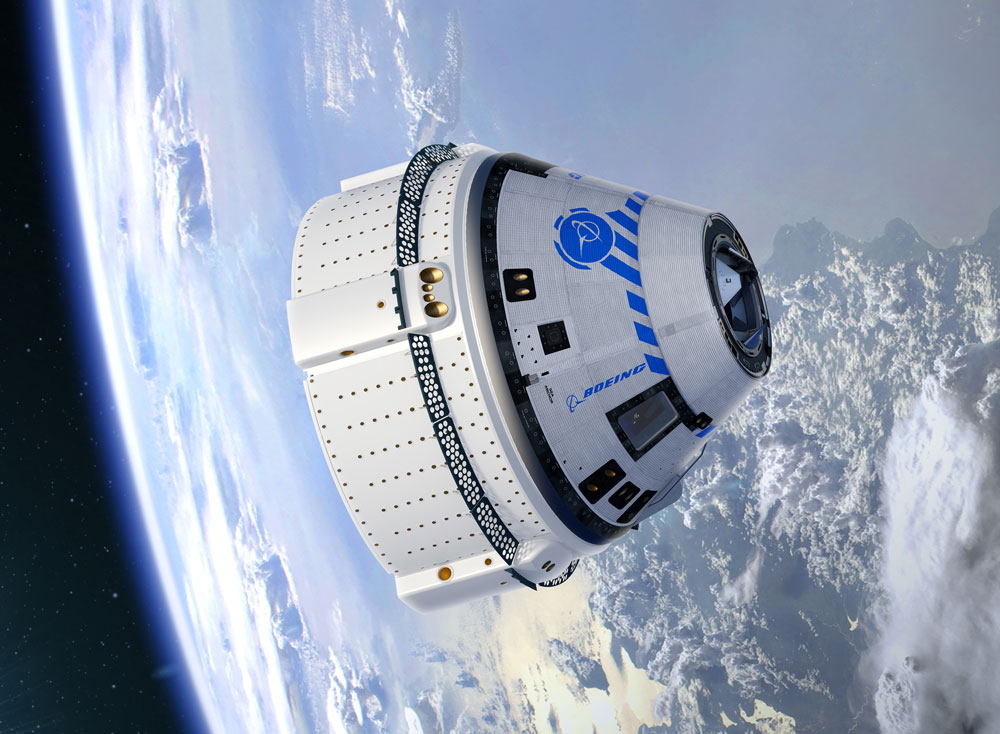

Boeing will be hoping to make up for lost time with its CST-100 Starliner.

Boeing will be hoping to make up for lost time with its CST-100 Starliner.

It has been building for some time – but 2021 feels like a turning point for commercially delivered space exploration. Private, risk-bearing companies now have capabilities previously only within reach of rich nation-states. This year will see reusable launchers, crewed orbital and suborbital flights and lunar landings – all delivered on a pay-for-what-you-use basis. In truth, many of these capabilities have only been possible as a result of customers (often the US government) with very deep pockets – but the trend is clear and the results will be lasting.

It is also a significant year for China, eager to consolidate its position as a first-tier space nation for both a domestic and international audience. In the year of the Ox – a symbol of strength and determination – the first Chinese Mars rover will touch down and a new space station will go up. European nations will need to up their game (and their spending) if they wish to hold a place at the top table.

The UK is a nation awakening to the role of space in the 21st Century – and not a moment too soon. Secure communications, resilient position and time services, access to space, surveillance and tracking (of and from space) – these are must-have tools for a self-determining, influential and robust player on the world stage. Thankfully, considering the economic uncertainty brought by Brexit and Covid-19, they are capabilities that are increasingly affordable… but what is affordable for the UK is for others as well. The country has a very capable – but fragile – technical base from which to build in a notoriously protectionist global market. The UK government has shown increasing vision and ambition for space in recent years. This year will be a test of commitment.

It will also be a year of change for the UK Space Agency – a new (as yet unannounced) CEO; a shift towards delivery of programmes (away from its policy-based comfort zone); the National Space Council finding its feet (and voice?); working out what it means to own a major stake in OneWeb; clearing the way for domestic launch; winning back lost ground in the EU’s Copernicus programme; and difficult choices around sovereign satellite navigation capabilities. Hard work ahead? Certainly – but fortune favours the brave.

Space science and exploration

Readers of AEROSPACE magazine will also recall that 2020 was a significant year for Mars mission launches (AEROSPACE, December 2020). Happily, that means that 2021 is a significant year for Mars mission arrivals. Although ESA’s mission missed the launch window, the UAE (‘Hope’), US (‘Mars 2020) and China (‘Tianwen-1’) all had successful lift-offs.

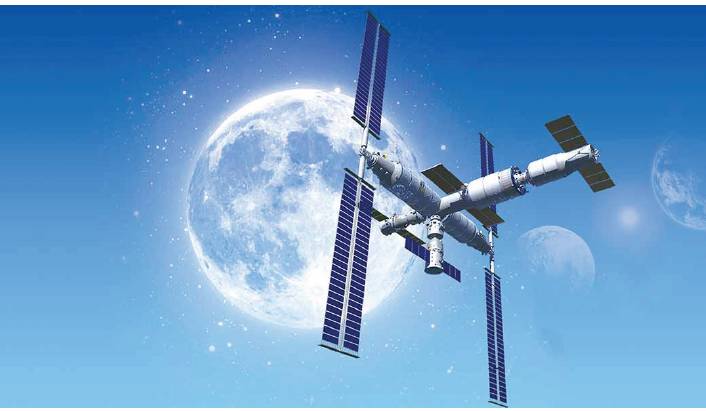

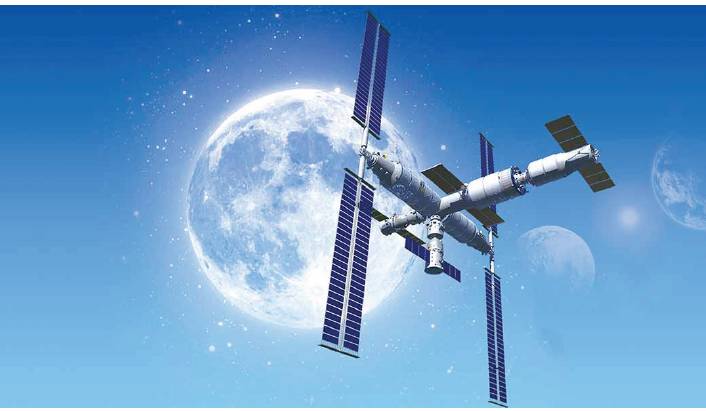

Earth is set to get a second space station in orbit this year with China’s Tianhe-1. CMSThe Chinese and American missions both carry landers with rovers. Mars 2020’s lander even includes a helicopter as a technology demonstration. For a while, at least, there may be three operational rovers on Mars – and a chopper – at the same time (recalling that the earlier Curiosity rover is eight years old and still going…). The nature of planetary alignments and transfer orbits means that all three missions arrived within a few days of each other last month.

Earth is set to get a second space station in orbit this year with China’s Tianhe-1. CMSThe Chinese and American missions both carry landers with rovers. Mars 2020’s lander even includes a helicopter as a technology demonstration. For a while, at least, there may be three operational rovers on Mars – and a chopper – at the same time (recalling that the earlier Curiosity rover is eight years old and still going…). The nature of planetary alignments and transfer orbits means that all three missions arrived within a few days of each other last month.

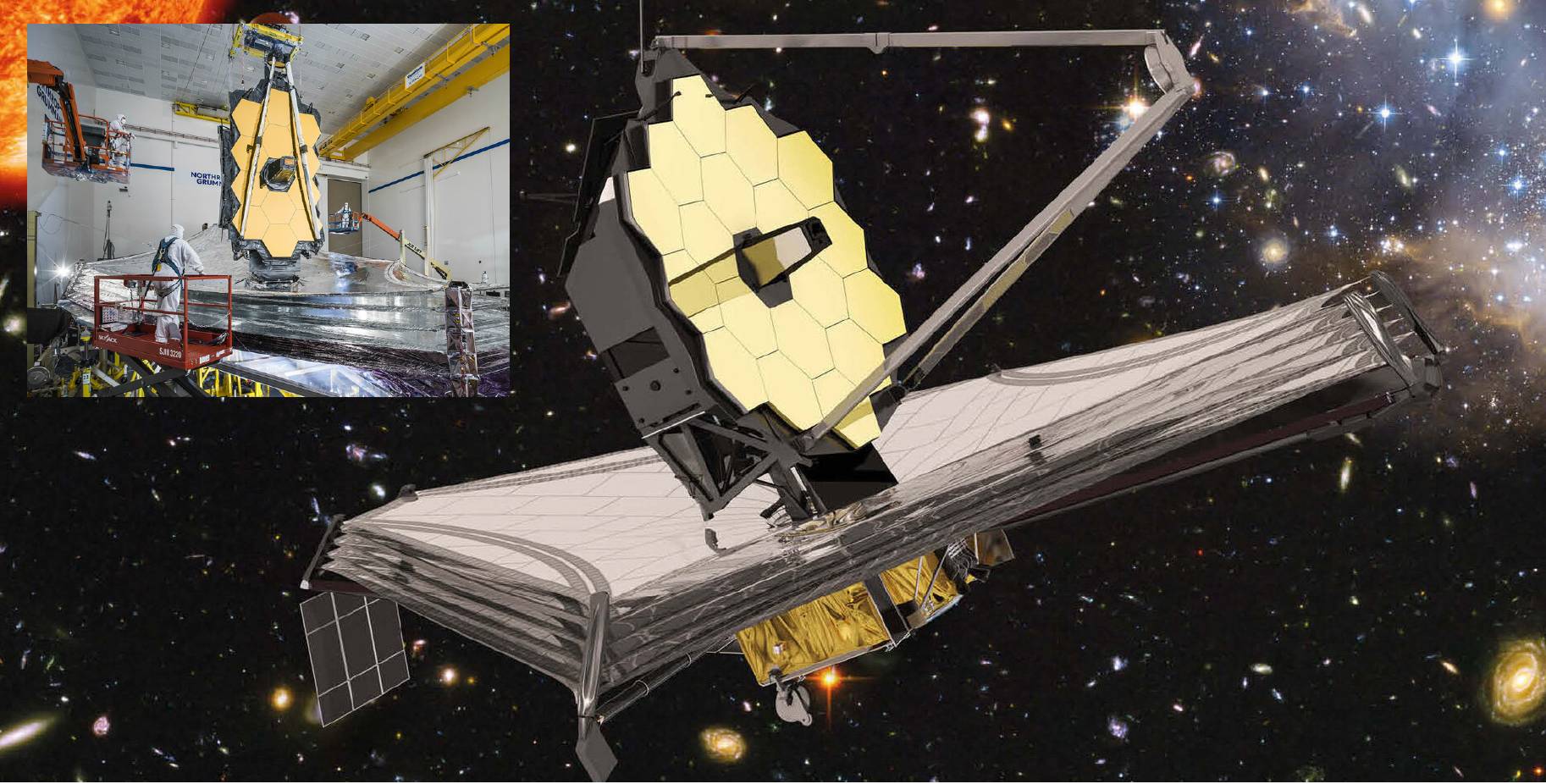

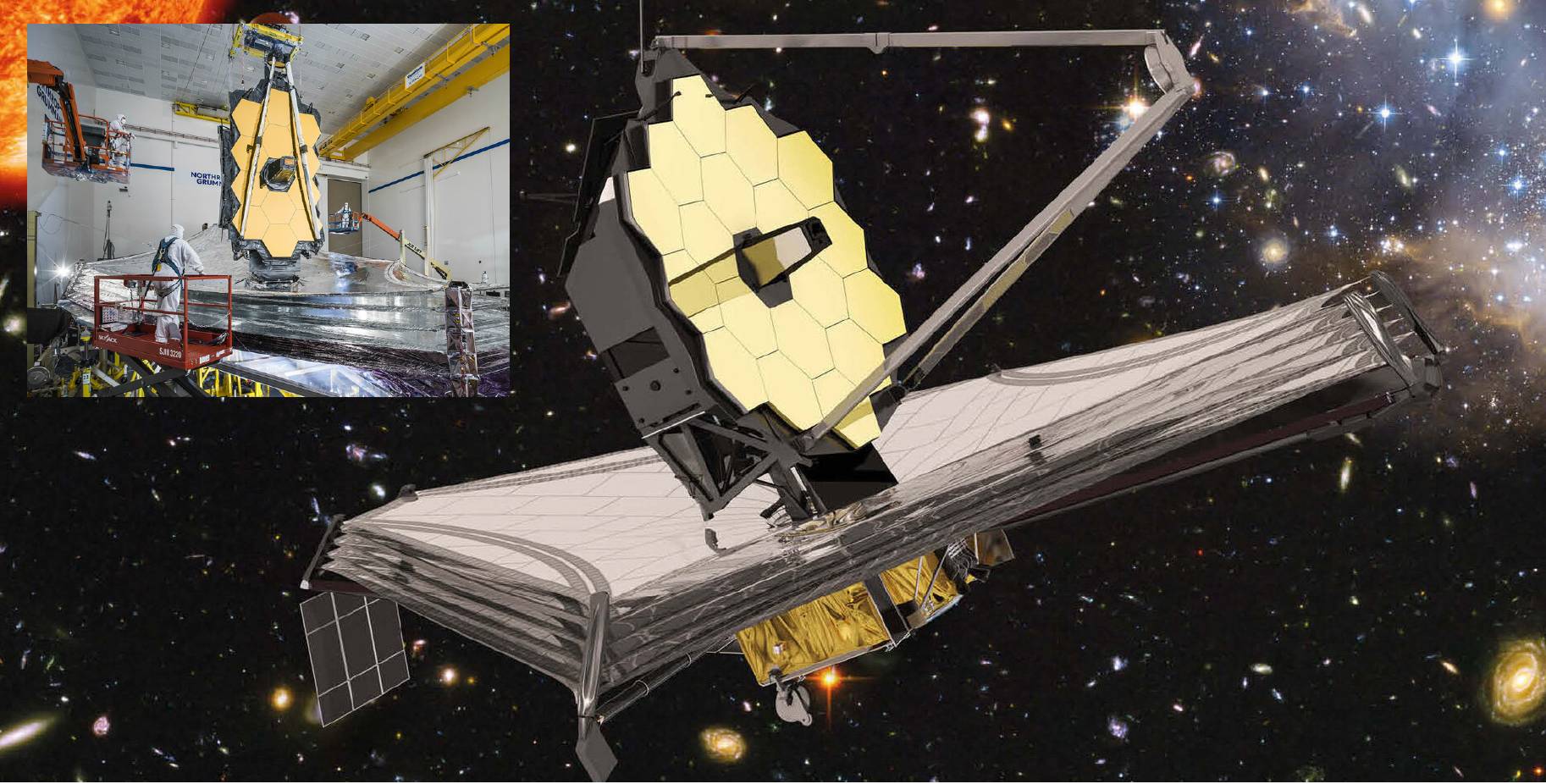

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, the early formation of the Universe put on a light show. This year, a mission that has also been a long time coming will finally let us watch. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), led by NASA and supported by ESA and the Canadian Space Agency, started its life back in the mid-90s. Its mission is to open up a new window on the very early universe. JWST, widely regarded as Hubble’s successor, carries a mirror nearly three times the diameter of Hubble’s and is sensitive to light mainly in the infrared range. That makes it very well suited to observing faint, strongly ‘red-shifted’ events from the distant early Universe. Originally slated for launch almost 15 years ago, and costing almost five times more than its original budget, it has travelled a long and demanding road, surmounting major technical challenges. A 6.5m diameter segmented, deployable mirror and instruments that need to operate at –220ºC clearly pose some difficulties! It might be 2022 before we see ‘first light’ but launch is scheduled for 31 October on an Ariane 5 ECA.

Interplanetary pinball continues for a number of other missions, swinging their way around the solar system. All are working their way slowly closer to the Sun, shedding energy with each planetary encounter. ESA’s Bepicolombo (Venus, then Mercury), NASA’s Parker Solar probe (Venus, twice) and ESA’s Solar Orbiter (Venus, then Earth).

Crewed space missions

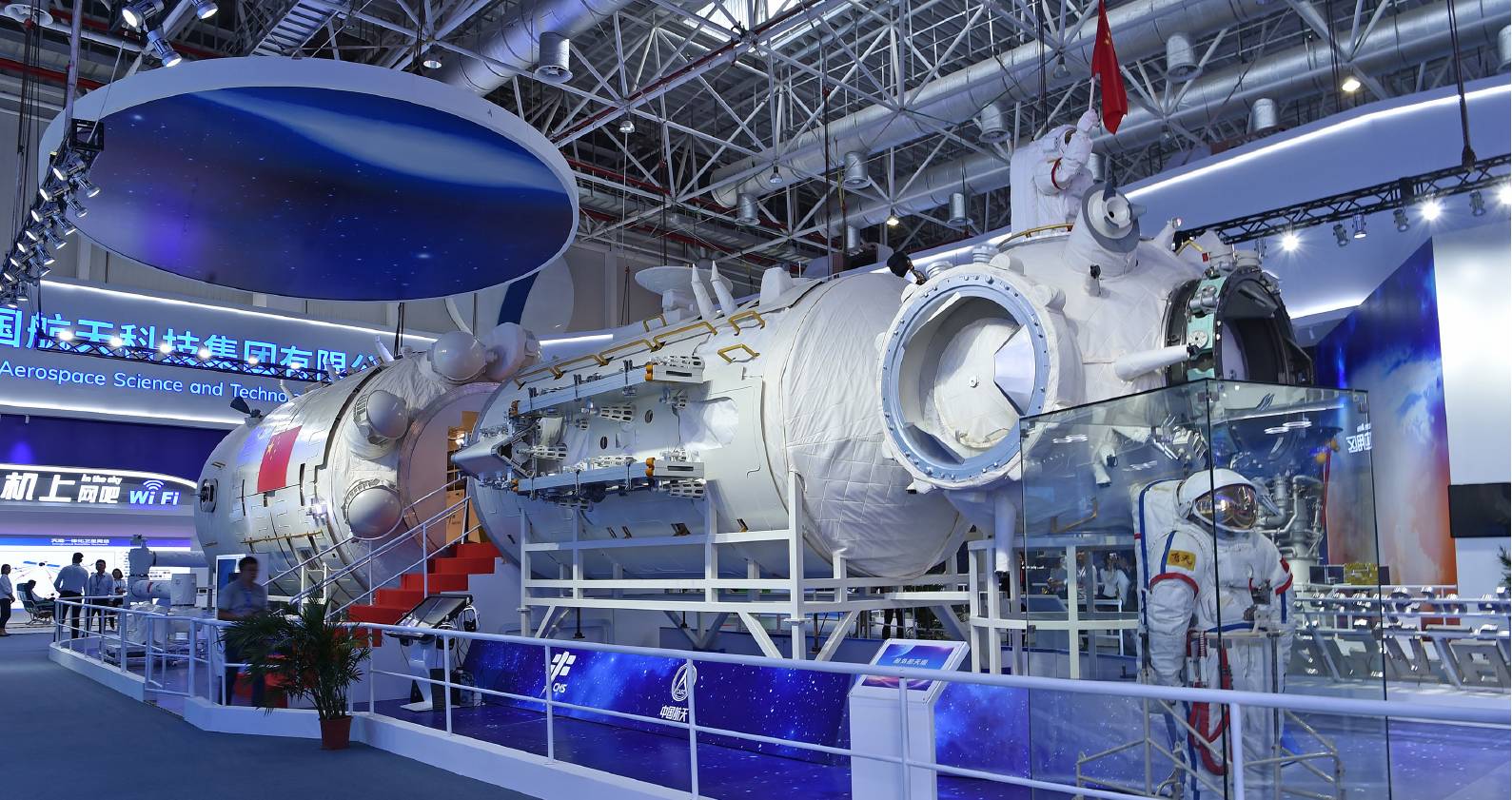

A second space station will join the International Space Station (ISS) in space this year with the launch before Easter of the 24t Tianhe-1 (Celestial Harmony) central module of three (to which solar arrays will be connected) of the Chinese Space Station (CSS). Two crewed visits to Tianhe are expected during the year, along with several robotic supply missions, as the CSS is gradually assembled. When complete, the space station will be comparable in size to the earlier Russian Mir station.

If the Chinese think they will capture the crewed spaceflight headlines with this demonstration of their space capability they are likely to be disappointed. The US plans to up its game with the launch of Tom Cruise and two other amateur astronauts to the ISS that is guaranteed to monopolise media channels. Tom and his buddies will be one of three or perhaps four flights of the SpaceX Crew Dragon in 2021. Two of these flights will carry European astronauts, Thomas Pesquet (French) and Matthias Maurer (German), alongside four Americans to start their six-month visits to the ISS, while the possible fourth mission will be a five-day flight for four tourists to an altitude twice that of the ISS.

The delayed first piloted test launch of the Boeing CST-100 Starliner capsule will be little more than a footnote by comparison with all this. Starliner will have to successfully complete its second uncrewed test flight before carrying astronauts into orbit. Software issues were encountered in the first orbital test (late 2019) which have taken longer than anticipated to resolve. Though originally aiming for a crewed second flight, Boeing took the decision to go again uncrewed before a first crewed flight to the ISS later in the year. The ‘service’ nature of the contract means that this second flight is at Boeing’s (shareholders’) expense. Noting software problems with tragic consequences elsewhere in the Boeing empire (737 MAX), the company will doubtless be strongly focused on ensuring a safe and successful mission.

While Boeing plays catch-up with SpaceX in outer space, two other actors – Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin – are lined up to compete for suborbital (straight up and down to ~100km) tourism. Virgin Galactic made its first ‘test passenger’ launch of SpaceShipTwo in 2019. This year should finally see paying customers gliding back to a runway-landing, including Sir Richard Branson himself. Blue Origin’s New Shepard, with its more ‘old school’ capsule and parachutes approach should also enter service. 2021 looks like being the year that space tourism finally comes of age.

Astrobotic’s Peregrine Mission One is one of NASA’s new breed of commercial lunar lander companies. Astrobotic

Astrobotic’s Peregrine Mission One is one of NASA’s new breed of commercial lunar lander companies. Astrobotic

Lunar exploration

At the end of 2020, China successfully brought back the first samples of lunar material for more than 40 years. The last time that happened was in 1976, by the Soviet Union’s Luna 24 mission. The sample is less than 2kg – but represents an impressive technical achievement and a significant scientific prize. The core samples come from up to 1m below the surface, in an area with some of the youngest lava flows (less than two billion years…!) – a treasure trove for lunar scientists.

For such a feat of engineering, the Chang’e-5 mission won relatively little press coverage in the UK. It is hard to say if that is a result of fighting for airtime with the Covid-19 pandemic or a public that is harder to impress. Either way, the US will seek to take back the initiative later this year via its commercial lunar payload services. Reflecting a growing theme in US space exploration, lunar landing ‘as-a-service’ is now the favoured approach. Three companies have been separately contracted, with two of them aiming to deliver their first payloads to the lunar surface this year.

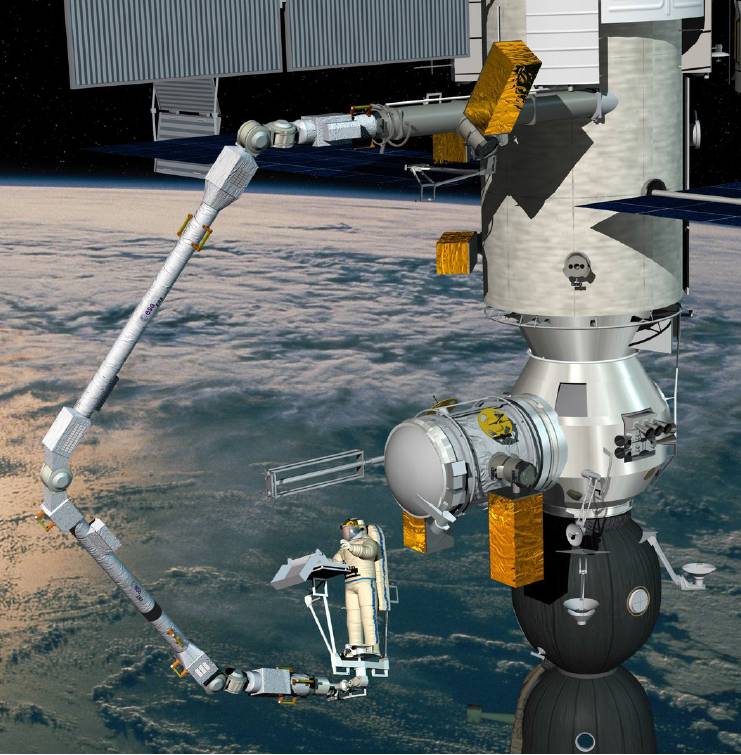

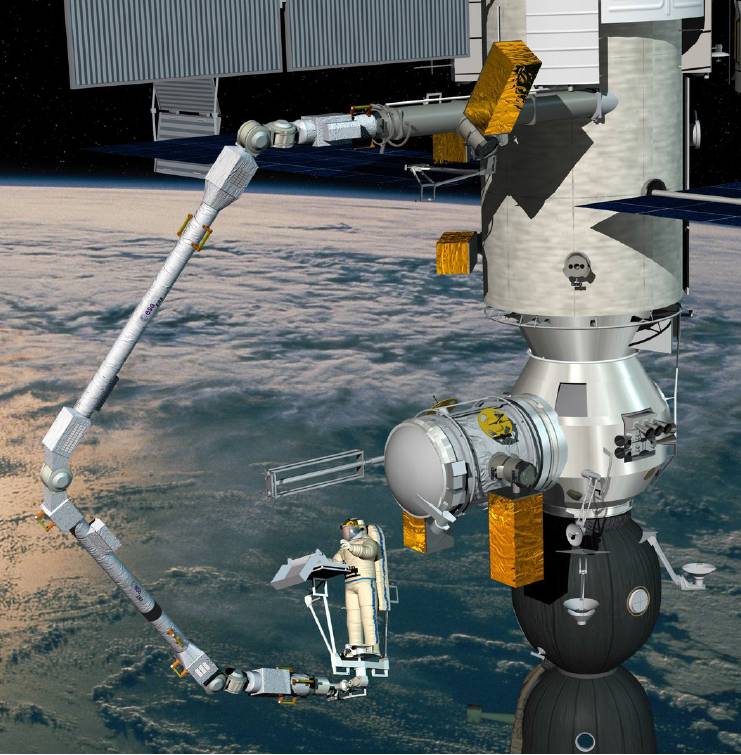

After many years of delays, ESA’s European Robotic Arm (ERA) will finally reach the ISS this year. Originally set for launch back in 2001, delays and the demise of the Shuttle programme left it stranded on the ground for many years. The ISS took delivery of spare parts for it back in 2010!

The ERA, similar in nature to the famous Canadian arm (‘Canadarm(-2)’), brings some valuable new features for the ISS. It will be the first arm able to operate from the Russian modules and is able to ‘walk’ itself in an automated way along the structure of the ISS by grasping with one end and then releasing the other.

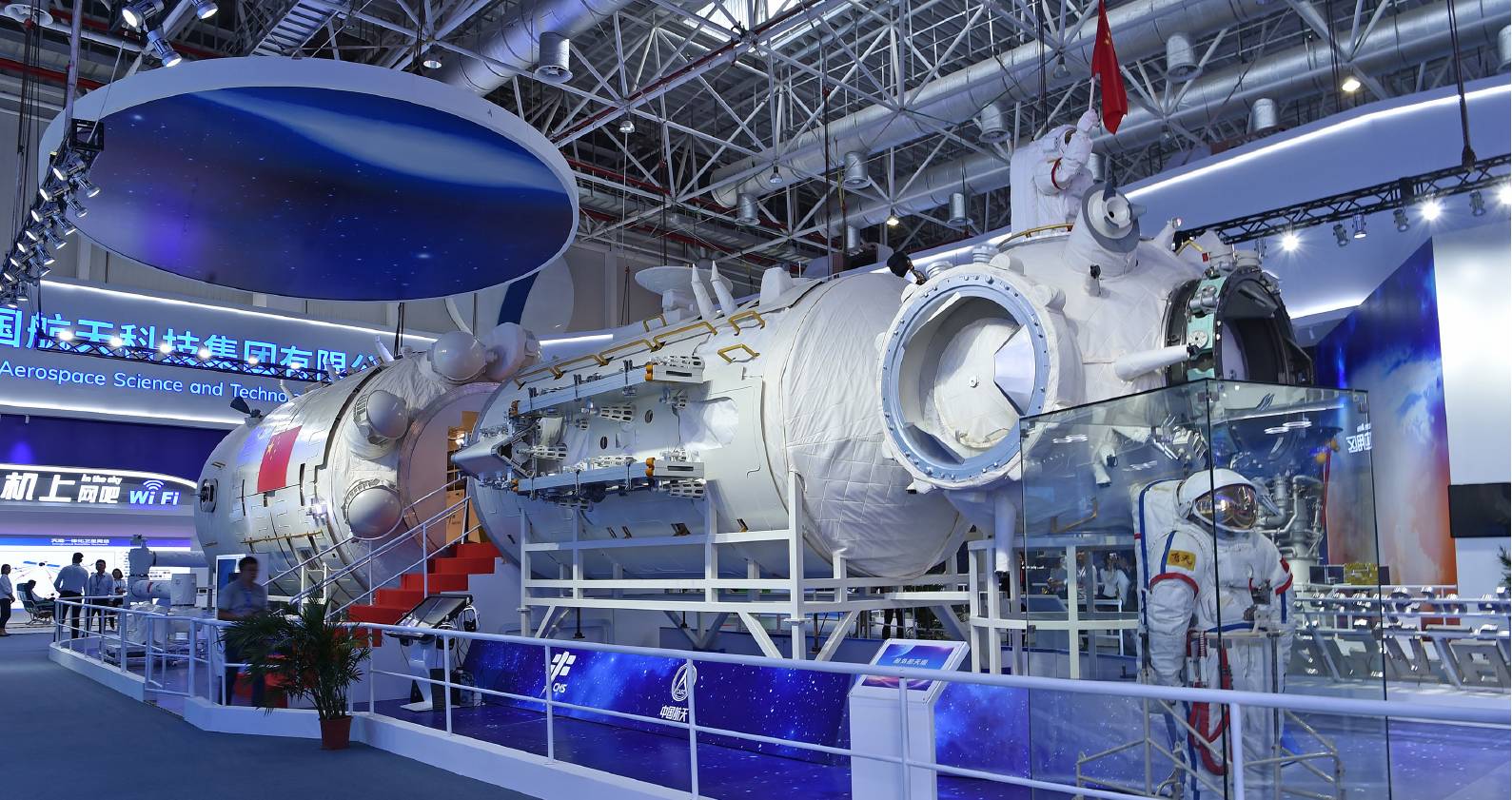

A full-size model of the core module of China’s space station, Tianhe. Xinhua/Liang Xu

A full-size model of the core module of China’s space station, Tianhe. Xinhua/Liang Xu

Military space in 2021

Surveillance, communications and positioning services using space assets are critical to the modern military. The US continues to rely mainly on large and expensive spacecraft for these functions – the most recent example being the launch into a high orbit on 11 December 2020 of a classified spacecraft with the code name USA 311 for the National Reconnaissance Office. Experienced space commentators have identified it as an ORION signals intelligence (SIGINT) spacecraft placed in geosynchronous orbit – an earlier example was called the ‘world’s largest satellite’ by the then Director of the NRO. Future launches in this class are not expected until 2022-23 but several smaller satellites with classified missions are due to be launched during 2021 as in previous years.

Meanwhile, United Launch Alliance (ULA) has only four more of the Delta 4 Heavy rockets used to launch USA 311 left in its inventory. The second half of 2021 should see the first launch of ULA’s new Vulcan rocket that is intended to take over from ULA’s Delta and Atlas families of rockets. This will also be the first use in a launch into orbit of the BE-4 rocket engine developed by Blue Origin (Jeff Bezos’ rocket company) which powers the first stage of the Vulcan.

ESA’s robotic arm will allow astronauts and cosmonauts on the ISS to grip on to things. ESA

ESA’s robotic arm will allow astronauts and cosmonauts on the ISS to grip on to things. ESA

Vulcan and SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets were selected in 2020 as the Department of Defense’s launchers for the next few years, ensuring that the big, heavy military satellites will continue to be deployed. In addition to geosynchronous SIGINT and missile warning satellites, the US also deploys surveillance (optical and imaging radar) and SIGINT systems in low Earth orbit.

Communications satellites make up another major part of US military space systems. The three main constellations are fully operational in geostationary orbits and no launches are expected until 2024: six AEHF satellites for strategic communications (augmented by payloads on lower orbit spacecraft to serve polar regions), five MUOS for communications on the move, and ten WGS for broadband services.

The latest generation of US positioning and timing satellites, GPS-III, is slowly being deployed in orbit and we can expect one or two more to be launched in 2021. Progress in deploying user equipment on the ground and the much delayed and over-budget OCX ground control system will continue but will be less visible.

Small spacecraft are increasingly used to explore new technologies and techniques for the US security community and we can expect three or four launches in 2021, some carrying multiple payloads. One of the US military’s iconic X-37B spaceplanes was placed in orbit in May 2020, so it is unlikely that we will see its return to Earth in 2021 since previous X-37B missions have typically lasted two years.(1)

Russian and Chinese military space

Russian military space activities are much less comprehensive than during the Cold War. Placing a satellite in close proximity to that of another country is one way of punching above its weight – the stationing of Cosmos 2542 relatively close to a US spy satellite in Feb/March 2020 being the most recent example. More Russian inspections of US and other satellites may well take place in 2021 as President Putin takes the measure of the Biden administration.

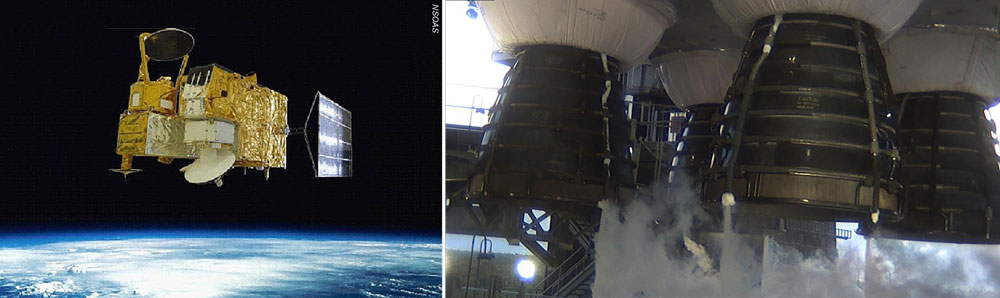

Three or four launches a year of the Chinese military surveillance satellites under the ‘Yaogan’ code name has been the recent norm and that is likely to continue. These low orbit satellites are thought to cover a variety of services, including optical and radar imaging, and SIGINT (especially maritime). The dual-use Gaofen series of high-resolution optical imaging satellites and HaiYang ocean observation satellites will probably also involve one or two launches each in 2021, as in recent years.

China also completed its 35-satellite Beidou navigation constellation in 2020, eliminating dependence on the US and Russia for these services. Launch of replacement Beidou satellites can be expected in 2021.

The final launch of 2020 was a French CSO reconnaissance spacecraft, the second of a planned three-spacecraft constellation. In late 2021, Italy will emulate this with the launch of the second of four COSMO-SkyMed Second Generation imaging radar satellites, while France is expected to launch the first of its Ceres operational SIGINT satellites.

Perhaps the most politically sensitive launch in 2020 was Iran’s 22 April launch of a military surveillance satellite, Noor, into a low Earth orbit. Although Noor is a six-unit cubesat and thus probably weighs less than 15kg, it triggered intense political reactions in the US and elsewhere. Will there be anything similar in 2021, for example from North Korea?

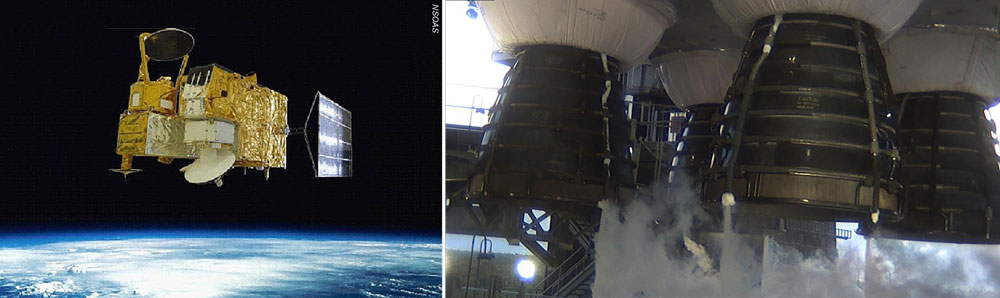

Left: The Chinese HaiYang-2A ocean observation satellite. Right: Testing for the core stage of the new Space Launch System but will Artemis and SLS stay on track under President Biden? NASA

Left: The Chinese HaiYang-2A ocean observation satellite. Right: Testing for the core stage of the new Space Launch System but will Artemis and SLS stay on track under President Biden? NASA

Launchers

SpaceX’s two-stage-to-orbit, fully reusable Starship launcher continues its test flight programme. The vehicle is intended to serve both as a heavy cargo lifter and for crewed missions, including to the Moon and beyond. A private circum-lunar tourism flight is already planned. Ten years ago, that might have seemed like ambitious marketing. Today, it feels like Gene Roddenberry’s ‘Wagon Train to the stars’(2) is getting ready to head out.

The initial uncrewed launch of NASA’s new super-heavy Space Launch System (SLS) was scheduled for November 2021 but failure to complete the full-up ground test of the SLS core stage on 16 January makes a 2022 date more likely. The first flight – for the Artemis 1 mission – is intended to demonstrate a launch capability for a human US return to the Moon. Artemis-1 will carry the US Orion capsule which incorporates a Service Module supplied by the European Space Agency. The Service Module is Europe’s ticket to get an astronaut to the Moon – certainly in orbit around the Moon and perhaps to the surface – as part of NASA’s return to the Moon initiative. The schedule for later Artemis flights is, however, shrouded in uncertainty as we await the impact on NASA’s Moon return budget of the Biden presidency accentuated by the fiscal drain of the Covid pandemic.

Other launcher programmes abound, large and small – from Blue Origin’s New Glenn through to Iran’s Qased and the UK’s Orbex Prime. According to some sources, up to 23 different launch systems may see their first flights in 2021(3). Doubtless, not all of these will go the distance – but the 2020s appear set to see an ‘explosion’ of launch systems.

Actual launch numbers in 2020 were double those seen during a low in the mid-2000s – regaining levels routinely seen through the 1970s and 1980s. There is now greater reason to believe that the growth will continue. Cheaper, more widespread and perhaps less controlled, launch technology is now an investment decision, as much as a strategic one.

The James Webb Space Telescope, as imagined in the main image and in production (inset), is set to be as significant as Hubble. NASA

The James Webb Space Telescope, as imagined in the main image and in production (inset), is set to be as significant as Hubble. NASA

Communications satellites

Fourteen times in 2020 the night skies blazed with the twinkling of 50 to 60 Starlink satellites being deployed from a single SpaceX Falcon 9 launch. As a result, 955 Starlinks were in their operational 550km high orbit at the end of 2020, single-handedly increasing the number of active satellites in orbit by about a third. There may be as many as 25 more launches in 2021 (one every two weeks), each carrying about 60 Starlinks – the first took place on 20 January. Beta testing of the 50-150Mbps of low latency broadband service is already under way in the US and a few other countries (including the UK) and operational service should begin in the summer of 2021.

Another amazing story in 2020 concerning low orbit (as opposed to geostationary orbit) communications satellites was the bankruptcy in March of OneWeb. It was then rescued in the summer via a joint $1bn investment from the UK government and India’s Bharti Global mobile network. December saw 36 new OneWeb satellites join the 74 already in orbit. Similar launches are planned roughly every month starting in February 2021. OneWeb claims that it will be able to offer a Beta version of its 400Mbps downlink megabits per second downlink and 100Mbps uplink service above 50° latitude (including the UK) by October 2021, although the full 640 satellite constellation operating at an altitude of 1,200km will not be in place until a year after that. Jeff Bezos’ Amazon is also planning to deploy a 3,000+ broadband satellite constellation called Kuiper at about 600km altitude but the date for the first launch has not yet been announced.

The small number of launches of geostationary orbit communications satellites foreseen for 2021 reflects the 2016-2019 trough in orders of such spacecraft. Among the dozen or so to be launched this year are four for Paris-based Eutelsat, including the innovative Quantum spacecraft (designed in Guildford and Portsmouth by Airbus) with its software-based design that gives it in-orbit reprogrammable features so that it can address markets that are highly changeable and mobile. Eutelsat’s first very high throughput satellite, KONNECT VHTS, will also be launched this year as will two satellites, HotBird 13F and 13G, to replace three that have been in orbit for more than a decade.

---

1. For more on US military space systems, see Norris P. (2020) Satellite Programs in the USA. In: Schrogl KU. (Eds) Handbook of Space Security. Springer, Cham, Switzerland.

2. A phrase Roddenberry used to describe his creation, Star Trek, invoking themes of the pioneer spirit and manifest destiny on the ‘final’ frontier.

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_orbital_launch_systems

Inaugural RAeS Mary Jackson Named Lecture – 25 January 2020, by Dr Moogega Cooper, the Planetary Protection Lead for the Europa Lander concept at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. www.youtube.com/Aerosociety/videos

Boeing will be hoping to make up for lost time with its CST-100 Starliner.

Boeing will be hoping to make up for lost time with its CST-100 Starliner.