This requirement is usually demonstrated in testing by the aircraft manufacturer, although analysis and partial testing has been accepted by National Aviation Authorities (NAAs), and in some cases, credit has been given for earlier tests on aircraft or variants with similar types of exits and/or exit configurations.

For the A380 25.803 evacuation test, Airbus assessed the agility level of test participants (passengers). This was the first time that such an assessment had been made prior to such a test. While there is no doubt that this may be a reasonable approach to protect test participants from unnecessary potential injury, it cannot be said to reflect normal line operations.

Future aircraft types and variants might be assessed by analysis and partial testing rather than full-scale testing. It is obviously desirable that test participants are not unnecessarily placed in ‘harm’s way’, but if there are shortfalls in the previous requirements of 25.803 then these shortfalls will be perpetuated in the certification of future aircraft.

Perhaps it might be questioned why the 25.803 requirements are only an airworthiness standard when actual evacuations are the responsibility of flight operations.

Possible shortcomings in the validation process

The 25.803 test criteria might, by default, result in a somewhat false emergency scenario, for example:

- The test participants know that an evacuation will happen and relatively soon after they have boarded the aircraft.

- Some test participants are employees of the manufacturer and will no doubt be well motivated to achieve a positive test result.

- The aircraft test crew may be from an operator (often the ‘launch customer’) who has ordered the aircraft and is likely to be similarly well motivated. They will have been specifically trained in evacuation techniques by the aircraft manufacturer shortly before the test.

- Although cabin baggage and blankets may be scattered throughout the cabin, the baggage is filled with low-density material and for which the test participants have no affinity – unlike their own cabin baggage.

- Historically, deactivation of the emergency exits has been such that there is always one of a pair of exits available. No 25.803 test has been identified where a pair of emergency exits has been deactivated.

- 25.803 tests are usually conducted in an orderly manner with passengers being co-operative rather than competitive.

- Given that such evacuation tests are conducted inside the controlled environment of a building, there are no weather conditions, such as wind, rain or snow that might have an adverse affect on evacuation slides.

The 25.803 test scenario also differs considerably from an actual emergency evacuation in which some or all of the following constraints may apply:

- The passengers will not be expecting or prepared for such an event.

- The aircrew may not have received their evacuation training shortly before an evacuation and it could be up to one year since their previous training check.

- The experience of a line cabin crew having to conduct an emergency evacuation might be less than a cabin crew specifically trained for a 25.803 test.

- In an actual evacuation where there is a perceived danger and threat to life, passengers are more likely to compete with each other to reach an emergency exit and, therefore, possibly to disrupt the flow of the evacuation.

- Passengers taking cabin baggage with them.

- Passengers taking photographic images.

- The number of usable emergency exits might be more or less than the 50% criteria and some pairs of exits will not always be available.

- The demographics of passengers in an actual evacuation will differ from those in a 25.803 test, such as children and infants, the elderly and those with reduced mobility.

Although some evacuations are subject to serious difficulties, such as unusable exits or evacuation slides, there are evacuations where most or all exits were available – but in spite of this the 90-second criteria was exceeded. There might be a number of reasons for this including:

- Delays in the flight crew, or, if necessary, the cabin crew, in commanding an emergency evacuation.

- Lack of communication between flight crew, cabin crew and passengers.

- Unserviceable communication equipment, such as public address and interphone systems.

- Crew not providing effective evacuation commands.

- Passengers not understanding the safety information they have been provided with.

- Passengers ignoring crew instructions, notably taking cabin baggage with them.

- Passengers experiencing panic and not being able to take appropriate actions.

Accident statistics demonstrate that, in a number of instances, either emergency exits were not usable or passengers took baggage with them or took photographic images during the evacuation or where the crew had no opportunity to specifically prepare the passengers for evacuation.

Pair or pairs of emergency exits not being available:

Aircraft type / Date / Location

Boeing 777-300 3/8/2016 Dubai, UAE

SSJ-100 5/5/2019 Moscow, Russia

Passengers taking cabin baggage with them:

McDonnell 27/1/2020 Mahshahr, Iran

Douglas MD-83

Boeing 737-500 9/2/2020 Usinsk, Russia

Passengers taking photographic images during the evacuation:

Boeing 737-500 9/2/2020 Usinsk, Russia

Airbus 2/10/2021 Atlantic City, USA A320- 271N

Passengers not specifically briefed by the crew for an evacuation:

Airbus A320-200 1/3/2019 Stansted, UK

SSJ-100 5/5/2019 Moscow, Russia

Only the most recent accidents have been listed above, indicating that the problems are still prevalent. Indeed, especially in the case of passengers taking baggage with them in an emergency, they are in fact becoming more frequent – undoubtedly because of the increasing perceived value placed by passengers on the contents of their cabin baggage.

Airbus A380 during evacuation testing in 2006. Airbus

Airbus A380 during evacuation testing in 2006. Airbus

Injuries sustained in evacuations

In any evacuation there is a potential for aircraft occupants to sustain injuries. This is true both of actual evacuations and 25.803 evacuation tests. Most injuries sustained by occupants in an evacuation are of a minor nature, such as friction burns and sprains caused by using evacuation slides. However, more serious injuries have also been recorded, such as fractured bones and in one 25.803 test a participant (passenger) suffered a life-changing injury. Placing passengers and crew in a potentially dangerous situation simply for the purposes of a 25.803 evacuation test is surely questionable, especially when other options might be available. NAAs should now consider alternative methods which might already be available, such as mathematical modelling.

Mathematical modelling

Mathematical modelling has the potential to replace or partially replace the actual testing requirements of 25.803. This could have the following advantages:

- Reduce or eliminate injury to test participants.

- Study variable factors seen in actual evacuations, such as pairs of emergency exits not being available, passengers taking baggage with them, actions of elderly persons or those with reduced mobility, etc.

- Enhance cabin crew evacuation procedures, taking into account variable factors, such as exit availability.

While mathematical modelling has several potential advantages, NAAs would need to be satisfied that for each model there is empirical evidence for satisfactory correlation to each factor being tested.

Availability of emergency exits

Some operators might base their cabin crew emergency evacuation procedures on recommendations made by aircraft manufacturers for specific aircraft. If such procedures are based on one of a pair of emergency exits always being available then in actual evacuations where this is not the case, such procedures might be compromised.

Potential future options

NAAs should carefully consider possible shortfalls in the 25.803 criteria. How many previous 25.803 tests would have successfully met the 90 seconds criteria if actual scenarios had been included, ie unavailability of pairs of emergency exits and passengers evacuating with their cabin baggage? If such testing is inherently flawed what might be possible options for the future? One way might be for NAAs to review previous 25.803 tests, now using mathematical modelling to see where the problems actually are and to see how crew members might best be trained to deal with the situations presented to them in an actual accident rather than a controlled test environment.

Summary

In 2020 the RAeS Specialist Paper entitled, Emergency Evacuation of Commercial Passenger Aircraft, recommended that NAAs consider the feasibility of introducing a certification requirement for means of remotely locking the flight deck overhead bins for taxi, take-off and landing, as well as other critical phases of flight. Given the number of recent accidents where passengers have taken baggage with them in evacuations, perhaps it is time for NAAs to now consider such a proposal. Fortunately, many recent evacuations were conducted safely but in more catastrophic events requiring more urgent actions, different outcomes might well occur.

The US Department of Transportation’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) has stated concerns “……..about the validity of the assumptions that drive FAA’s evacuation standards and industry tests and simulations for certifying new aircraft”. The OIG urges the FAA to review whether passengers really can evacuate a packed aircraft in the required 90 seconds. The OIG is of the opinion that, in emergency evacuations, issues, such as passenger behaviour and demographics, seat dimension, cabin baggage, and smoke in the passenger cabin, are important factors, some of which have changed in recent years and are not necessarily reflected in the FAA requirements for certification in 25.803.

The US Department of Transportation’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) has stated concerns “……..about the validity of the assumptions that drive FAA’s evacuation standards and industry tests and simulations for certifying new aircraft”. The OIG urges the FAA to review whether passengers really can evacuate a packed aircraft in the required 90 seconds. The OIG is of the opinion that, in emergency evacuations, issues, such as passenger behaviour and demographics, seat dimension, cabin baggage, and smoke in the passenger cabin, are important factors, some of which have changed in recent years and are not necessarily reflected in the FAA requirements for certification in 25.803.

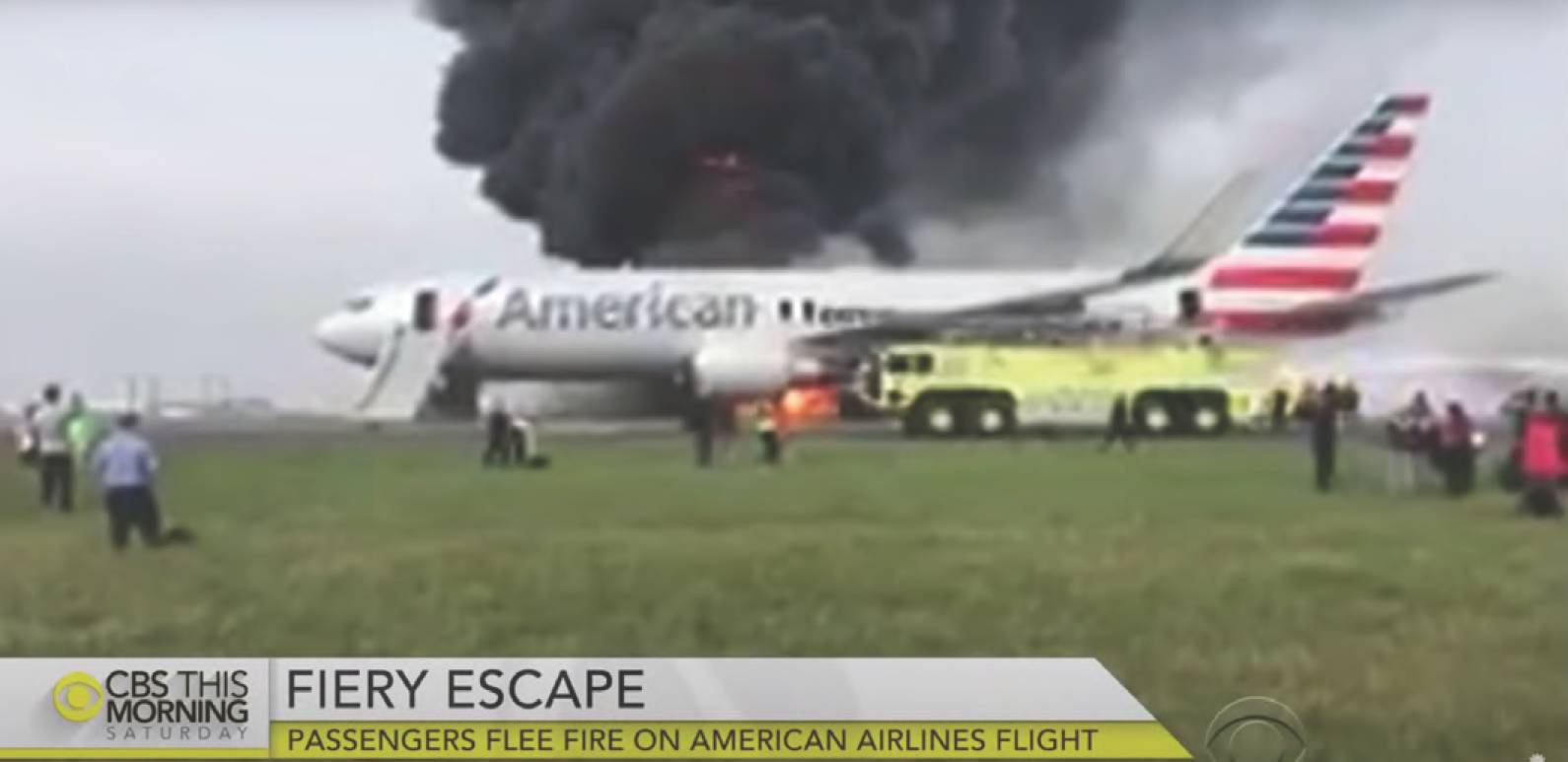

CBS

CBS