GENERAL AVIATION Personal air mobility

Jetpacks are Go!

ANTONY QUINN CRAeS, Royal Navy Commander and co-founder of Maverick Aviation which has created a semi-automated handsfree jetpack, explores the turbulent history of personal air mobility.

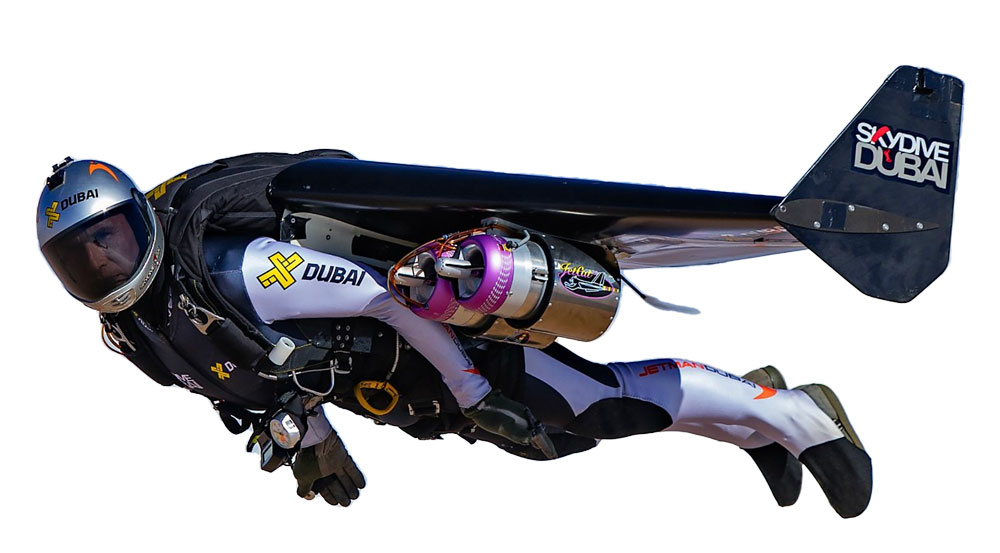

Maverick Aviation’s CTO Matt Denton wearing the company’s Jetpack. Maverick Aviation

Maverick Aviation’s CTO Matt Denton wearing the company’s Jetpack. Maverick Aviation

One afternoon in New York in the late 1950s, a rocket engineer named Wendell Moore offered an exciting new job to his neighbour’s teenage son. Moore needed someone with no previous flying experience to pilot a new experimental aircraft, and who better than the lad from next door who mowed his lawn? The US Army insisted that Moore’s Rocket Belt had to be flown by a non-pilot to demonstrate its viability for use by the average soldier. Unfortunately, it became clear that the Rocket Belt was one of the hardest systems to learn to fly and even today only a handful of people have ever flown the device. It remains firmly out of reach of the average soldier.

For nearly 80 years, militaries around the world have explored the use of jetpacks to solve short-range accessibility challenges. As recently as a few months ago, the US Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), launched a $2m funding opportunity for such a device. The situations for use are obvious and, arguably, needed as much today as during WW2, from accessing elevated objectives and avoiding obstacles in combat or rescue operations, to amphibious landings and vessel boardings in the maritime environment. It is not just the possibility of an operational advantage at stake: there are financial opportunities too. The current cost of vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) solutions is substantial, particularly when factoring in maintenance, ground crew and pilot training, let alone the airframe. Therefore, short-range personal air mobility that does not demand the infrastructure and costs of conventional aircraft could deliver considerable strategic benefit. However, despite nearly a century of attempts, the search continues.

The early years

The concept of a jetpack, or rather a rocket pack, using thrust from rocket engines was first conceived by a Russian named Alexander Andreev in 1919. At its essence, the design was simply a rocket motor contained within a backpack.

Bell Aerosystems Jet Belt. Williams International

Bell Aerosystems Jet Belt. Williams International

While a patent was granted, the device was never built or even prototyped. Just over two decades later, and after Buck Rogers brought the concept into the psyche of sci-fi fans, it was the Nazis who first experimented with building a device like this. The secret Nazi project codenamed Himmelstürmer or ‘Sky Stormer’ (sic), was destined to allow Nazi combat engineers and infantry to cross rivers, minefields and other obstacles with ease.

Not so much flight as 70m long jumps aided by a small pulse jet, fed by a separate oxygen tank. It was still in the experimental stage by the end of the war and only one prototype survived. Regrettably, there are no publicly available images of the system. After the war, the designs and prototype were handed by Germany to the US and passed to Wendell Moore and his team at Bell Aerosystems in New York.

Moore was the first person to engineer what we would recognise today as a jetpack. After three years of rig-testing, the US Army gave $25,000 to Bell Aerosystems to build an operational prototype and, in April 1961, the Rocket Belt had its first free flight.

Using technology that Bell had originally developed for the US space programme, the design was strikingly simple but shamelessly hazardous. Pressurised nitrogen contained in a central tank next to the wearer’s spine is used to push hydrogen peroxide from the two outer tanks through a silver catalyst. The chemical breakdown in the catalyst generates high-pressure steam which provides enough thrust to lift the apparatus and its wearer into the air.

Thrust from the steam is vectored by the pilot using lever-controlled nozzles to provide directional flight. Film reels of early demonstrations show graceful manoeuvres over obstacles, rivers and terrain. However, what is not apparent from the footage is the many months of tethered and zipline training needed to reach a safe level of competence to fly. Bill Suitor, arguably one of the world’s most accomplished jetpack pilots (and of course Wendell Moore’s neighbour’s son), describes learning to fly the Rocket Belt like “trying to balance while standing on a beach ball on the ocean”.

In addition to the extensive training burden, military audiences were also underwhelmed by the weight of the system, the deafening 130dB soundtrack and the agonisingly short 21-second flight time.

Jetpack joyride

Unsurprisingly, the US Department of Defense did not continue funding the Rocket Belt but the benefits of personal air mobility felt within their reach and, in 1965, a new research contract was placed to extend the flight time using a jet engine. Williams developed the WR19, a small-scale turbojet engine with a thrust of 1,900N to replace the hydrogen-peroxide rocket. This allowed Moore and the Bell team to achieve a vastly improved five-minute flight time with the kerosene-powered, vectored no nozzle ‘Jet Belt’.

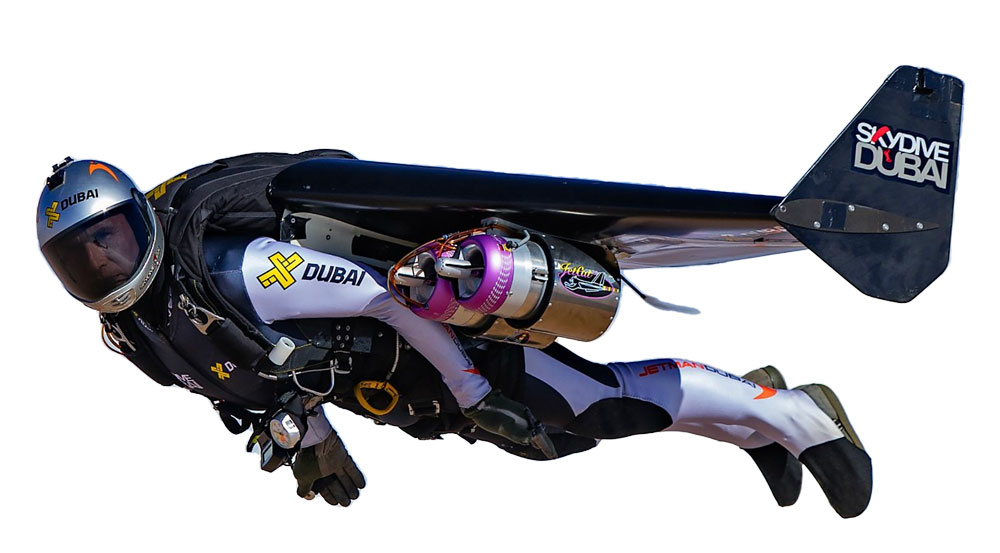

Yves ‘Jetman’ Rossy and his Jet Wing. Jetman Dubai

Yves ‘Jetman’ Rossy and his Jet Wing. Jetman Dubai

However, it is not just about time in the air that makes something a viable military capability. The Jet Belt was very complex to maintain. It was so heavy that there was a risk of spinal injuries on landing and it was still as difficult to learn to fly as the beach ball Rocket Belt. The US Army lost interest again and the Jet Belt project ended. The WR19 engine was later used on the Tomahawk TLAM missile and most other US missile systems since the 1980s so the Jet Belt programme was indirectly very profitable for those companies involved.

Just a few weeks after the JJet Belt’s first free flight, Wendell Moore died from heart problems and nothing really changed with the technology for the next few decades. The single tu rbine engine Jet Belt design was never seen again but the hydrogen-peroxide Rocket Belt was demonstrated all around the world for stunts and entertainment. It was used by Sean Connery (or rather Bill Suitor) in the James Bond film, Thunderball as well as at the opening ceremony of the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles and even Michael Jackson ‘flew’ it on stage at a concert tour in 1992.

The courageous few

Digital twin of the semi-automated Maverick flight control system. Maverick Aviation Ltd

Digital twin of the semi-automated Maverick flight control system. Maverick Aviation Ltd

A handful of resourceful individuals around the world have built their own versions of the hydrogen peroxide-powered Rocket Belt over the years, although there was nothing particularly new from a technological point of view.

One of these systems was built for David Mayman, with the help of Nelson Tyler, but this device just represented a stepping stone on a journey leading to gas turbine-powered flight systems and the creation of the company, Jetpack Aviation. Experimenting with micro gas turbines used predominantly by radio-controlled hobbyists, Mayman and Tyler’s design iterations evolved from a dozen small engines in 2006 to just two engines a decade later.

The revolutionary twin-engine JB10 boasts 160kg of thrust, 15,000ft maximum altitude, 120mph forward flight speed, duration of 10 minutes, FAA Certification, and support from the US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM). Impressive statistics from true pioneers in the field. However, with a fuelled-up weight of around 60kg, and a challenging control interface designed by pilots for pilots, this jetpack still remains out of reach of the average soldier. Instead, the company has recently shifted focus to a winged motorcycle version of their technology, the Speeder air utility vehicle.

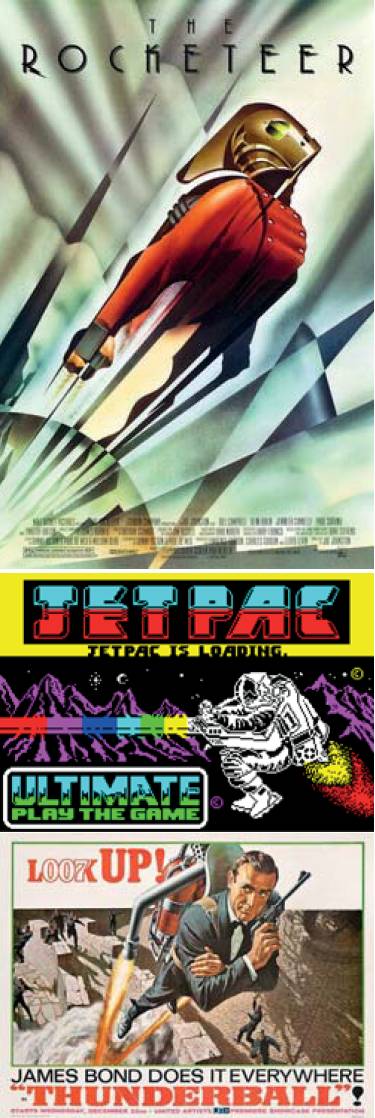

Top to bottom: The idea of the jetpack has always held a special fascination in the minds of many across popular culture, as can be seen in The Rocketeer film adaptation of the 80s graphic novel, a much loved 80s ZX Spectrum computer game and the 1965 James Bond film, Thunderball. Walt Disney/Ultimate/Danjaq, LLC and Eon Productions

Top to bottom: The idea of the jetpack has always held a special fascination in the minds of many across popular culture, as can be seen in The Rocketeer film adaptation of the 80s graphic novel, a much loved 80s ZX Spectrum computer game and the 1965 James Bond film, Thunderball. Walt Disney/Ultimate/Danjaq, LLC and Eon Productions

Former Swiss fighter pilot, Yves Rossy presented another approach with his micro gas turbine-powered Jet Wing invention.

By wearing a 2.4m carbon-fibre aerofoil, the additional lift allows him to reach speeds of 180mph at typical aircraft altitudes for up to 20 minutes. Launching from a helicopter and landing with a parachute means the uses have so far been limited to exciting marketing stunts and record-breaking. Recent adaptations have proven a nascent VTOL capability but the 2.4m wing is a completely impractical adornment while your feet are on the ground.

The use of a parachute is noteworthy; below an altitude of around 20ft a fall would be survivable, above 300ft and a parachute could be used. However, between those altitudes, survival is unlikely as there is insufficient time for a parachute to deploy. This is why most jetpack operators choose to fly low and typically over water when possible.

Tragically, despite being the only personal air mobility system fitted with a parachute, a Jet Wing training flight resulted in the death of pilot Vince Reffet in 2020 when he fell from 800ft but did not deploy his canopy. The investigation is yet to determine why.

Franky Zapata has earned a star in the aerial mobility ‘hall of fame’ with his minimalist Flyboard Air, using micro gas turbines but this time contained within a small platform fixed to a pair of boots. Taking off and landing from a raised steel platform, the French inventor wears a rucksack full of kerosene and combines a hand-held throttle with almost superhuman core strength and balance to shift his own centre of gravity for directional flight.

A successful crossing of the English Channel in around 20 minutes (with a quick boat landing to refuel halfway) highlights the incredible capability of the system but his recent uncontrollable spin and crash reveals the obvious risks. Despite a generous €1.3m grant to develop the capability, the French Defence Innovation Agency described the system as not ready for military use due to its difficulty to fly. In 2017, however, USSOCOM funded tests of an easier variant of the device, the EZ-Fly, which resembles a flying Segway and showed some promise for military use cases.

Ubiquitous across social media is the Gravity Industries’ Jet Suit, created by British inventor, Richard Browning who wanted to augment the human body with just enough technology to be able to fly.

With a single micro gas turbine on his back and two further turbines on each arm, Browning vectors thrust to achieve VTOL and around five minutes of directional flight just by moving his arms and body. Its simplicity is what makes it so brilliant, and once a pilot has spent long enough flying the Jet Suit, it really does become an extension of the person.

A recent series of impressive trials flown by Browning with the police, military and mountain rescue have made the early use cases of the 1960s look tantalisingly plausible. Altitude, speed, and stability of the Jet Suit are all a function of cognitive and physical self-control and while a tethered hover is probably achievable for some people after a week of intense training, mastering the system for safe free flight takes a very long time.

The next generation

The inescapable drawback with all the designs discussed here is a considerable time needed to learn to fly safely off-tether. Lengthy pilot training is a well-established necessity in the world of conventional aircraft, but in the field of wearable aircraft when the paramedic, engineer or marine must fly themselves without relying on a professional pilot, then the training pipeline is critical for feasibility. Once mastered, jetpack flying is as intuitive as riding a bicycle, but to reach that skill level typically takes many months or years of training.

With 21 seconds, or even 5 minutes before refuelling, training becomes a time-consuming and expensive endeavour. Swift mastery was a key user requirement in the 1960s, and six decades of innovation has still not delivered it. However, this could be about to change, thanks to the ground-breaking work of UK-based newcomers, Maverick Aviation, of which I am co-founder.

The Maverick Aviation semi-automated Jetpack.

The Maverick Aviation semi-automated Jetpack.

The company’s Chief Technology Officer, Matt Denton has developed an innovative jetpack that is virtually effortless to fly because, for the first time for a wearable flight system, the Maverick Jetpack has an auto-stabilised flight control system. Elegantly bridging sci-fi and the real world, Denton is an award-winning Hollywood robotics and control systems engineer who has worked on all the recent Star Wars films, Jurassic World and the Harry Potter franchise. Maverick received funding from the UK government to build a concept demonstrator for the onshore and offshore energy industry, and our first successful flights occurred in 2021.

Flying this jetpack is as intuitive as operating an electric drone but with up to 150kg lift capacity, thanks to powerful gas turbine engines. It might sound like a straightforward technical challenge to apply drone-like stabilisation to jet engines, but jets are not responsive enough to allow the necessary rapid and constant thrust adjustments.

So, we have developed a novel system combining rapid changes in thrust vector with changes in thrust magnitude to achieve stability and directional flight. Throw in the unpredictable and shifting centre of gravity of a human and you realise the ingenuity behind the Maverick flight control system.

Developing this unique technology has been possible by creating an accurate ‘digital twin’ of the entire system, including the operator, to use as a sandbox for experimentation.

Safety is addressed with multiple reversionary modes and even engine redundancy and, thanks to its sophisticated flight computer, an autonomous ‘hail function’ will allow the Maverick Jetpack to fly uncrewed to your location before you clip in and fly effortlessly away. The company is currently raising funds to take its technology to market and, with patents pending and a military contract secured, the use of Maverick Jetpacks for rescue, security, and entertainment may well be on track to becoming a familiar sight.

In a world where uncrewed aerial vehicle usage is burgeoning, there will always be times when you need an expert on task quickly; whether that’s an engineer, paramedic, Marine, or just your average Joe, finally they will soon all be able to fly – hands-free, and with minimal or no training.

Maverick Aviation’s CTO Matt Denton wearing the company’s Jetpack. Maverick Aviation

Maverick Aviation’s CTO Matt Denton wearing the company’s Jetpack. Maverick Aviation