Afterburner

Book Reviews

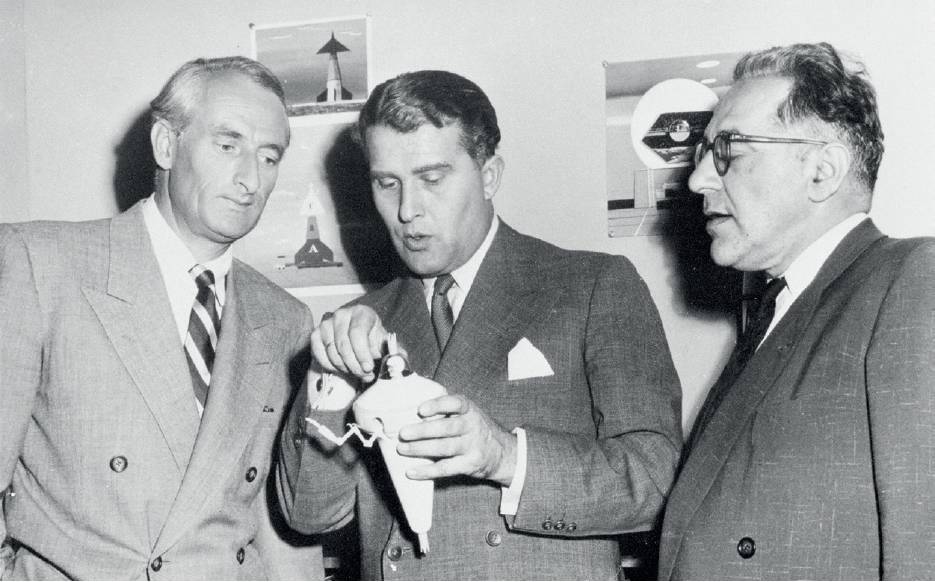

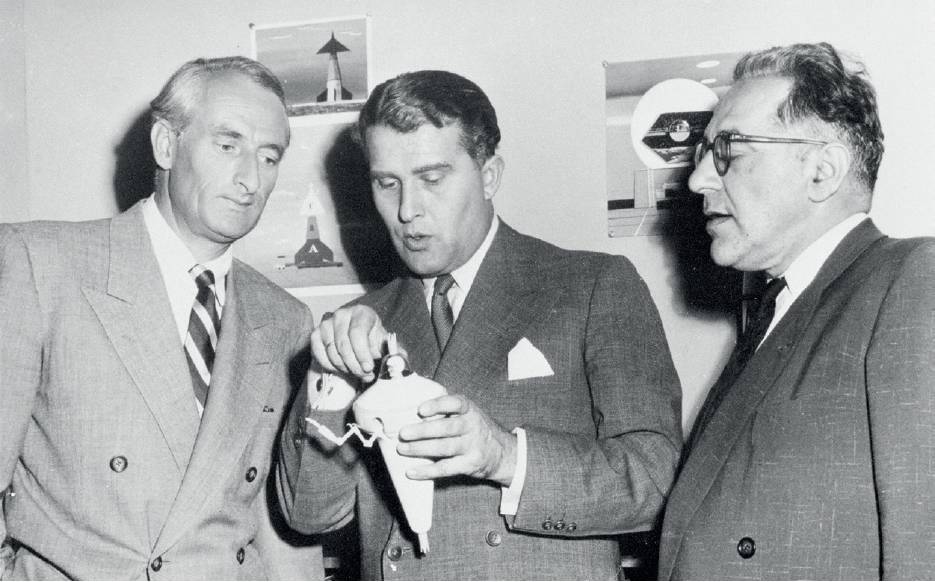

WILLY LEY

Dr Wernher von Braun

(centre), then Chief of the

Guided Missile Development

Division at Redstone Arsenal,

Alabama, discusses a ‘bottle

suit’ model with Dr Heinz

Haber (left), an expert on

aviation medicine, and Willy

Ley. NASA

Dr Wernher von Braun

(centre), then Chief of the

Guided Missile Development

Division at Redstone Arsenal,

Alabama, discusses a ‘bottle

suit’ model with Dr Heinz

Haber (left), an expert on

aviation medicine, and Willy

Ley. NASA

Prophet of the Space Age

By J S Buss

University Press of Florida, 15 Northwest 15th Street, Gainesville, FL 32611-2079, USA. 2017. xiii; 322pp. Illustrated. $34.95. ISBN 978-0-81305443-8.

This book provides the first full-length biography of Willy Ley, a most prolific German-born populariser of science, engineering and particularly astronautics and as such is a valuable addition to the literature.

A Chesley Bonestell

painting of a spaceship on the

surface of the Moon. From:

Willy Ley The Conquest of

Space (New York: The Viking

Press. 1950).

A Chesley Bonestell

painting of a spaceship on the

surface of the Moon. From:

Willy Ley The Conquest of

Space (New York: The Viking

Press. 1950).

Born in 1906 in Berlin, Ley became enthused with space travel in his teenage years, as did many others, by the writings of Hermann Oberth and Valier. He was an active member the VfR [German Rocket Society] formed in 1927 and it was there he first met Wernher von Braun. Although Ley appears to have attended lectures in several German universities, he did not receive a formal university education.

Ley left Germany in 1935 for the US. By this time he was becoming known for his publications on rocketry and space travel and was in correspondence with G Edward Pendray of the American Rocket Society and Phil Cleater of the British Interplanetary Society.

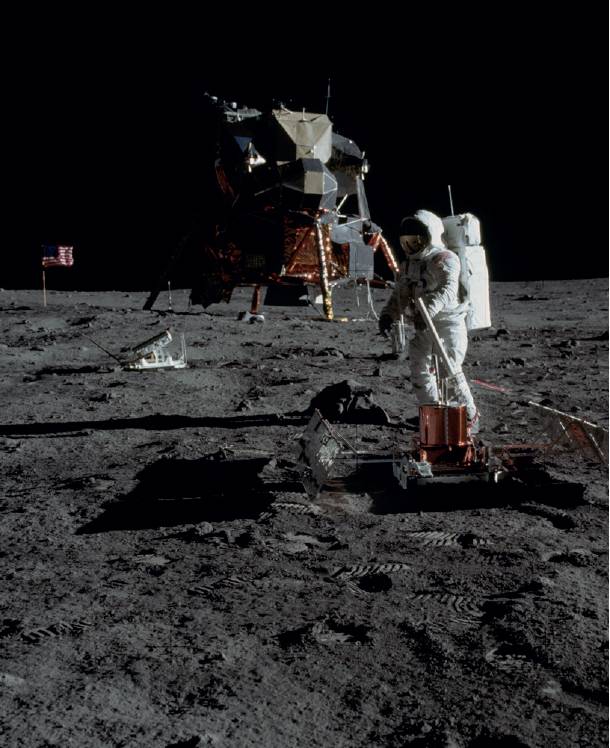

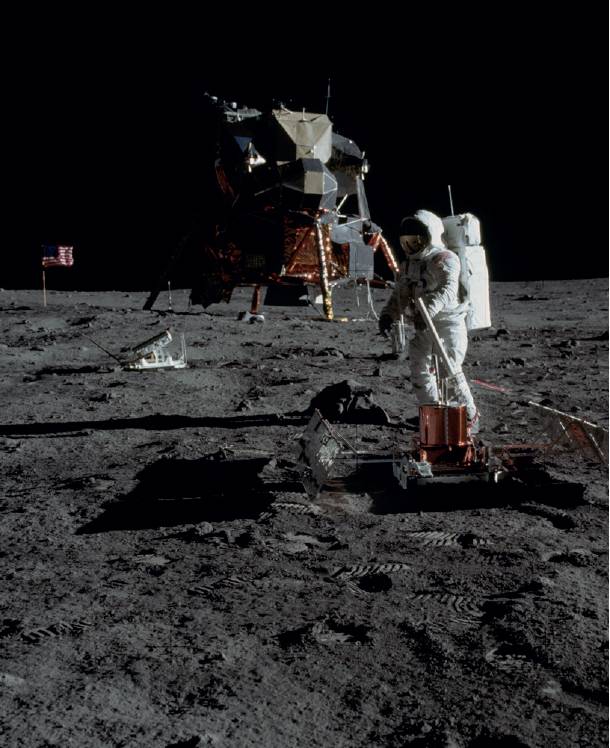

For comparison,

only two months after Willy

Ley died, Neil Armstrong took

this picture of Buzz Aldrin,

lunar module pilot, deploying

the Early Apollo Scientific

Experiments Package

(EASEP) during the Apollo 11

extravehicular activity on the

Moon. NASA.Buss’ well-researched book describes in depth Ley’s contributions to the public understanding of space and other scientific disciplines through his books, articles, science fiction stories and the radio and TV media. It is not an easy read. There are many excerpts from Ley’s works but, at the end of the book, I still felt that I did not know much about Ley as a person or as a family man.

For comparison,

only two months after Willy

Ley died, Neil Armstrong took

this picture of Buzz Aldrin,

lunar module pilot, deploying

the Early Apollo Scientific

Experiments Package

(EASEP) during the Apollo 11

extravehicular activity on the

Moon. NASA.Buss’ well-researched book describes in depth Ley’s contributions to the public understanding of space and other scientific disciplines through his books, articles, science fiction stories and the radio and TV media. It is not an easy read. There are many excerpts from Ley’s works but, at the end of the book, I still felt that I did not know much about Ley as a person or as a family man.

Ley made his name by explaining aspects of the scientific world to the general public. His interests were eclectic, ranging from spaceflight though zoology to palaeontology. He is probably best remembered in the space world for his seminal volume Rocket: The Future of Travel Beyond the Stratosphere (New York: The Viking Press. 1944).

Ley also wrote prolifically on other subjects particularly in the history of astronomy and the natural sciences. He did attempt to become an engineer in the space world in the late 1940s but this came to nothing.

He remained an outsider looking in and became a very influential commentator during the 1950s and 1960s, collaborating with Chesley Bonestell, Walt Disney and von Braun. It is a sad fact that, bearing in mind his contributions to popularising space travel, Ley died two months before the Apollo Moon landing in 1969.

John Becklake

THE HISTORY OF HUMAN SPACE FLIGHT

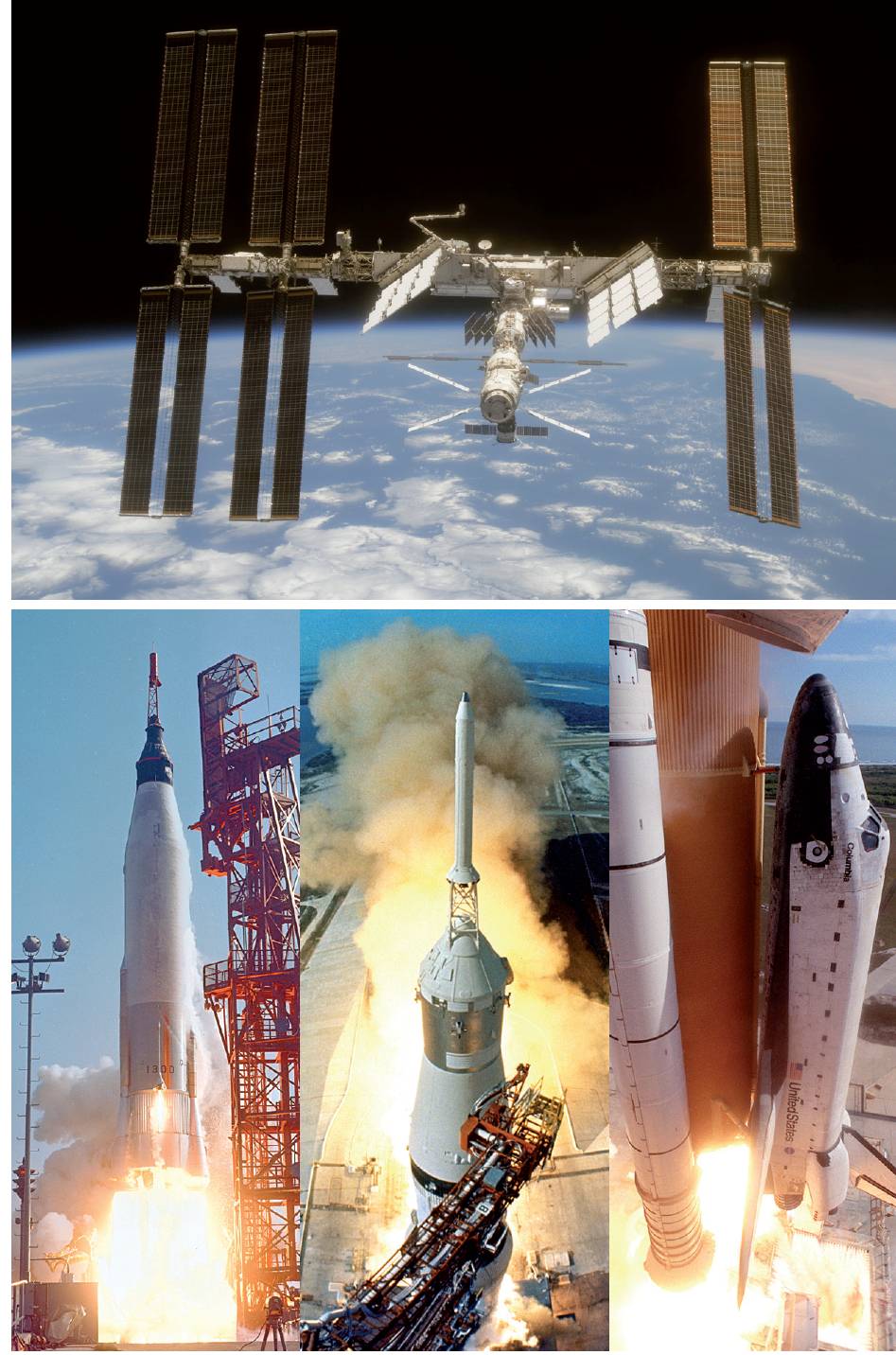

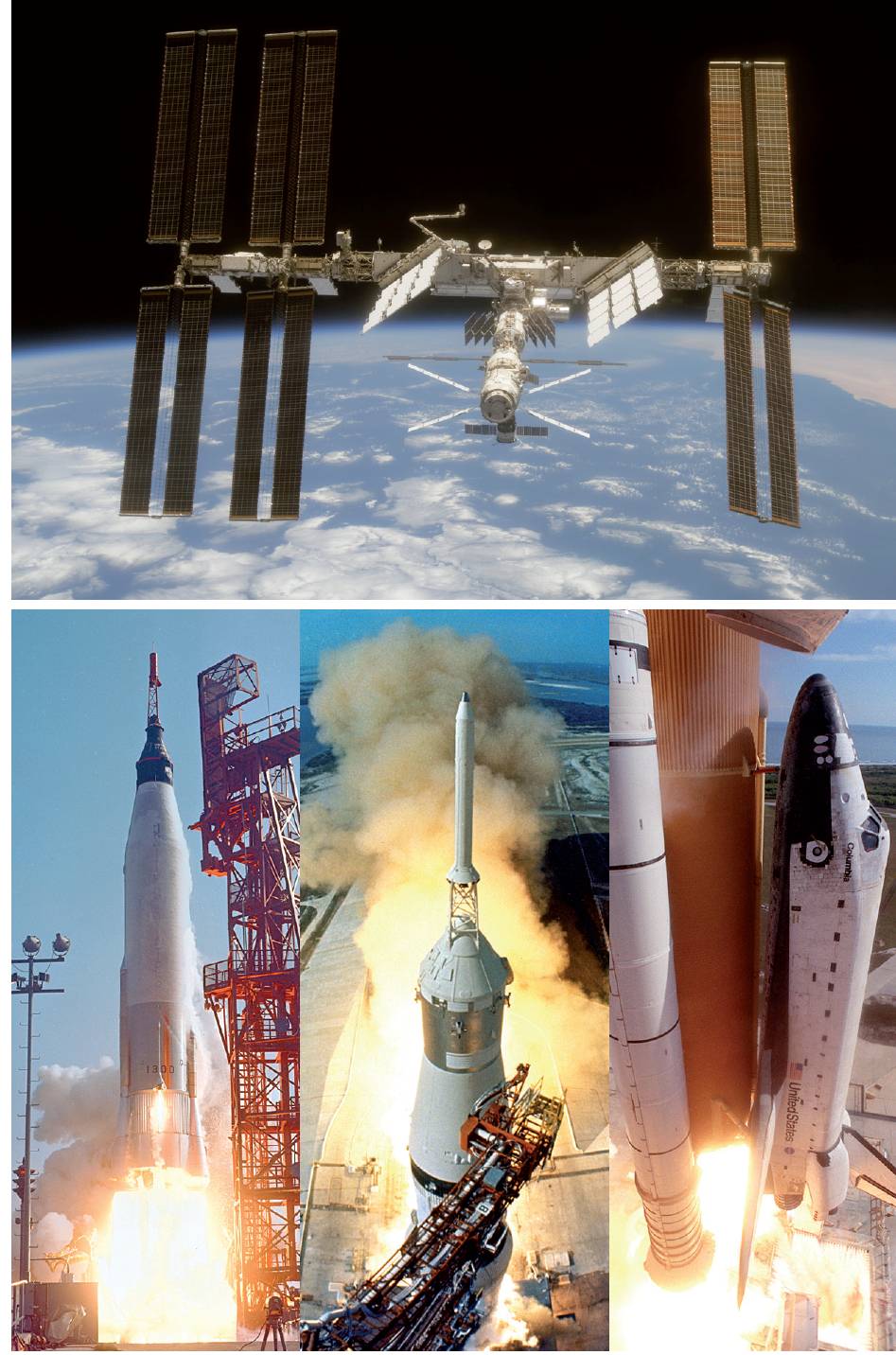

Top: The International Space Station as seen from Space Shuttle Discovery during Mission STS-124

in June 2008. NASA.

Above left: Mercury-Atlas 9 lifts off from Pad 14 on 15 May 1963 at Cape Canaveral with astronaut

L Gordon Cooper aboard Faith 7. NASA.

Above centre: 9:32am EDT on 16 July 1969, the swing arms move away and signals the lift-off of

the Apollo 11 Saturn V from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A. NASA.

Above right: Space Shuttle Columbia as it lifts off from Launch Pad 39A on Mission STS-107 on 16

January 2003. It was destroyed during re-entry on 1 February. NASA.

Top: The International Space Station as seen from Space Shuttle Discovery during Mission STS-124

in June 2008. NASA.

Above left: Mercury-Atlas 9 lifts off from Pad 14 on 15 May 1963 at Cape Canaveral with astronaut

L Gordon Cooper aboard Faith 7. NASA.

Above centre: 9:32am EDT on 16 July 1969, the swing arms move away and signals the lift-off of

the Apollo 11 Saturn V from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A. NASA.

Above right: Space Shuttle Columbia as it lifts off from Launch Pad 39A on Mission STS-107 on 16

January 2003. It was destroyed during re-entry on 1 February. NASA.

By T Spitzmiller

University Press of Florida, 15 Northwest 15th Street, Gainesville, FL 32611-2079, USA. 2017. xiv; 634pp. Illustrated. $39.95. ISBN 978-0-81305427-8.

This is a comprehensive story of mankind’s desire to travel into space and achieve a landing on the surface of the Moon and beyond. It is quite a weighty publication having over 600 pages of text, diagrams and photographs and an appendix of terminology. The author has carried out a great deal of research into the subject but one is not too overloaded with statistics to digest.

The book starts with the origins of flight and the first ascent of humans by balloon. This progressed to achieving high altitude flight. The definition of the commencement of space I learnt is 62 miles above the Earth’s surface. Man’s first high altitude ascents were in capsules and it was appreciated at early stage the effect of hypoxia that could be induced with possible fatal consequences. More conventional flight in powered aircraft with the ever-increasing desire to attain higher speed and altitude are of course well documented.

The Space Race forms an essential part of the background and, until I read this publication, I was unaware that John F Kennedy was not that interested in space. I was also not aware that so many potential astronauts had died in tragic circumstances before they even got the chance to go into orbit. Various crashes in conventional aircraft led to this scenario.

The USSR got the first man into space but a lot of information about the loss of life in their space programme did not come to the attention of the public until many years after and this book gives an insight into these facts. The American failures were much more high profile, particularly with the loss of both the Challenger and Columbia Space Shuttles. I was amused to find that the first Shuttle Enterprise was so named after pressure from Star Trek fans!

There were also some lucky escapes from potential disaster by the USSR and, of course, with Apollo 13.

The book left me in awe at how much has been achieved in such a short time.

I found that the more I read, the more engrossed I got. It was wonderful to be aware that there was after many years huge collaboration between countries that were deemed to be arch enemies. China of course has its own space programme.

From a British point of view, I was disappointed that there is no mention of Helen Sharman who was our first cosmonaut aka astronaut and on a Soyuz mission to the Mir space station. However, Michael Foale receives recognition possibly because he was a NASA astronaut. Space Station and the enormity of the task makes fascinating reading.

Paul Robins

Former photographer for the Science Museum and Royal Aeronautical Society

THE JET ENGINE STORY – A REVIEW

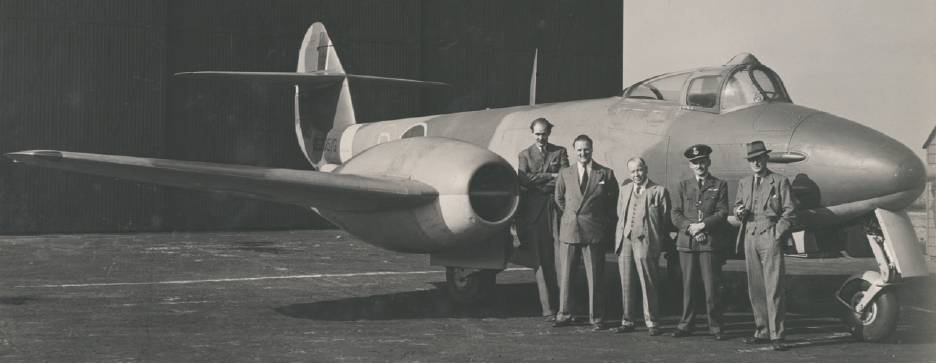

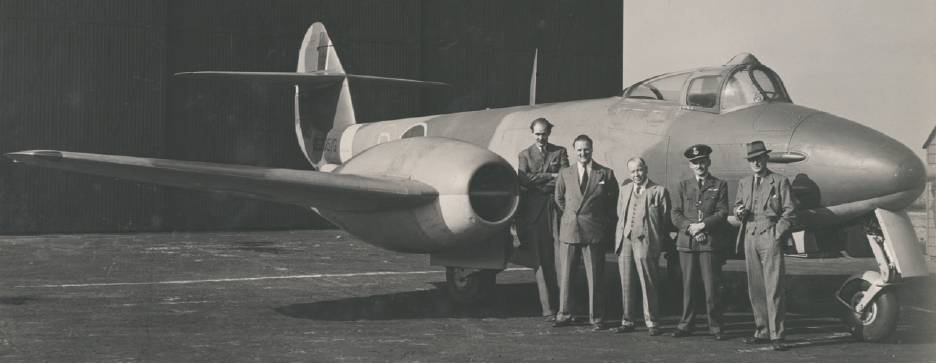

The fourth prototype

Gloster F9/40, DG205/G,

forerunner of the Meteor,

with, from left, John Crosby-

Warren, test pilot; Michael

Daunt, test pilot; Frank

McKenna, md, Gloster; Air

Cdre Frank Whittle and W G

Carter, Chief Designer, later

Technical Director, Gloster.

RAeS (NAL).

The fourth prototype

Gloster F9/40, DG205/G,

forerunner of the Meteor,

with, from left, John Crosby-

Warren, test pilot; Michael

Daunt, test pilot; Frank

McKenna, md, Gloster; Air

Cdre Frank Whittle and W G

Carter, Chief Designer, later

Technical Director, Gloster.

RAeS (NAL).

A review of the early British jet engine story, particularly in relation to Frank Whittle, and a comparative summary of early activity in other countries that pioneered jet engines. A library and research resource. FAST Monograph 004

By B Howard

Farnborough Air Sciences Trust, Trenchard House, 85 Farnborough Road, Farnborough, Hampshire GU14 6TF, UK (E manager@airsciences.org.uk). 2019 (revised edition). 197pp. Illustrated. £15.

Over the past 70 or so years, many books, papers and articles on ‘The Jet Engine Story’ have been published – understandably, as the new kind of propulsion had a transforming effect on aviation. So, we now have a large body of literature by authors having a variety of viewpoints and credentials. Inevitably, there still exist gaps in information, factual uncertainties and conflicting interpretations that stand in the way of a definitive history and understanding.

The aim of Mr Howard’s book is to assist in the improvement of this situation regarding the parts of the British history particularly related to Frank Whittle – an area which has given rise to significant controversy. Howard’s approach is to encourage a more critical reading of the published literature, by selecting significant events and issues and comparing and commenting on the accounts given by various authors.

In the UK innovative ideas about future aircraft engines sprang independently from two sources, namely A A Griffith at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) in 1926 and Whittle in the RAF in 1928/29. This then resulted in two pioneering streams of research and development, leading eventually to the ‘first generation’ British jet engines derived from Whittle’s work using centrifugal compressors, soon followed by RAE-derived engines with axial-flow compressors as used in most major engines today.

However, the progression from first ideas to engines in operational service was by no means straightforward for either the Whittle or the RAE project. Official assessments in late 1929/early 1930 did not result in Air Ministry support, with the result that both projects then remained at a standstill for over five years!

Practical progress recommenced in 1936. Whittle AEROSPACE / JULY 2019 and some friends formed a small company – Power Jets Ltd – and with limited funds raised commercially, embarked on a venture to build and test a complete experimental turbojet engine. In the same year Hayne Constant, who was to become a central figure in the RAE story, returned to RAE to work under Griffith after an absence in academia, and approval was gained for an experimental axial-flow compressor. This was the first of a series of multi-stage research compressors designed at RAE over the next several years. The resulting test data, combined with Griffith’s earlier work, led to an RAE design method for axial compressors that formed a vital contribution to the achievement of efficient axial-flow engines.

A Whittle gas turbine

in a disused foundry at

Lutterworth. A scene from

the COX film The Wonder Jet.

RAeS (NAL).

A Whittle gas turbine

in a disused foundry at

Lutterworth. A scene from

the COX film The Wonder Jet.

RAeS (NAL).

In April 1937 Whittle achieved the first testbench run of his engine – an event of significance both technically and in terms of demonstrating to sceptical minds the practicability of his turbojet concept. Following an assessment of recent technical progress, and the increasing operational attraction of higher speed combat aircraft, the Aeronautical Research Council (ARC) recommended that the Air Ministry should now press ahead strongly with gas turbine development, with the addition of assistance for the two pioneering groups from selected manufacturing companies.

As both projects proceeded, a collaborative relationship grew between Power Jets and RAE, reflecting a mutual respect developed between Whittle and Constant. An example was the secondment of some able RAE personnel, headed by Dr (later Sir William) Hawthorne, to assist Power Jets in dealing with combustion system difficulties.

Relations of the two pioneering groups with their respective industry colleagues were initially good and remained so throughout the RAE collaboration with Metropolitan-Vickers. However, this was not so for Power Jets where, firstly, disagreements with British-Thompson-Houston (BTH) led to a change to Rover as manufacturers of the Whittle experimental engines, followed later by progressive deterioration in Power Jets/Rover relations that eventually resulted in Rolls-Royce taking over entirely from Rover in early 1943 and becoming responsible for getting the Whittle-type engines into RAF service in mid-1944 in the Meteor fighter.

Air Cdre Sir Frank Whittle

KBE CB. RAeS (NAL).

Air Cdre Sir Frank Whittle

KBE CB. RAeS (NAL).

The early 1940s proved a difficult time for Power Jets. Although the initial engine flight testing in 1941 was strikingly successful, development of a more powerful engine, the W2, intended for RAF service was highly troublesome, with serious problems of engine surging and component failures leading to redesign work and programme delay. Whittle was operating under strain and his health suffered. In addition to the technical workload was his anxiety regarding what he saw as possible threats to Power Jets from vested interests in industry, and increasingly difficult relationships with some official circles.

A notable government reaction to the Power Jets problems was that in late 1940 Sir Henry Tizard became concerned about progress and created an additional industry centre for jet aircraft and engines by inviting de Havilland to enter the field. This went very well, leading eventually to the widely used Vampire fighter and its centrifugal-flow Goblin engine. An early version of this engine became available for flight three months before the Whittle W2B and was used to power the early flights of the Meteor.

Early in 1944 a great blow to Whittle’s longer-term hopes was the Ministry decision that the design, development and production of gas turbine engines should be the province of the existing aero-engine industry, while Power Jets and the RAE gas turbine group would be combined as a nationalised company responsible for research and associated activities. However, Whittle and his team had aspired to a leadership status in mainstream engine design and development. An unhappy period followed, culminating in Whittle’s resignation in 1946, followed by many of his original team. So ended Whittle’s role as a pioneering leader in the jet engine story. Although he received many honours and awards, and became world-famous, Whittle did not occupy any major position in the aero-engine field after retiring from the RAF in 1948. It is understood that an industry post was considered but agreement on terms was not reached.

From the story sketched briefly above, Howard selects for examination a number of Whittle-related topics. Space precludes a complete listing here but to provide an impression a few examples are given below:

- Whittle’s relations with Griffith, who as a government scientist was involved in the Air Ministry 1929 assessment of Whittle’s turbojet ideas. Whittle always felt Griffith could have been more supportive – although it was Griffith who in 1935 put forward what was probably the first design scheme for a turbojet for use in a specific aircraft project!

- The likely significance, in the 1937 assessment, of the advent of UK radar warning systems in increasing the attractiveness of turbojet engines which could provide defensive fighters with very high speeds though with relatively short endurance.

- The possible effects of Whittle’s recurrent health problems on his difficult relationships with other organisations and individuals, which sometimes gave rise to tensions that were unhelpful to progress.

- The strong disagreements between Whittle and Rover regarding ‘productionising’ the W2 engine, and the Rover preference for a ‘straight through’ combustion system rather than the Whittle ‘reverse flow’ design.

- The contrast between Whittle’s hopes, and the Ministry decision regarding the future of Power Jets.

Although Howard emphasises that his central purpose is to help and encourage his readers to develop their own opinions about the published accounts of this area of aeronautical history, he does also outline his own conclusions. His main feeling is that biased writing and simplistic interpretation of events and issues is regrettably common in some of the best known and widely read books.

He observes that often in such cases the authors have a journalistic background and style, contrasting with the more impartial and objective approach typical of those having a professional engineering or academic standpoint. Summarising, he cites the writings of R O Schlaifer, A Nahum and G P Bulman (edited by M C Neale) as providing “much the better insight into, and accuracy of, the jet engine story and of Whittle’s activities in relation to it” – an opinion which this reviewer strongly endorses!

This book is the outcome of a big effort by Howard in gathering, sifting through and critically appraising a very large amount of material. It should be helpful to many who would value a better understanding of this piece of UK aeronautical history and the people involved but would find difficulty in committing the large amount of time and effort to the kind of extensive survey now made available by Howard.

The book is easy to use, extracts and quotations discussed in the main text being clearly linked to their source references, showing specific page numbers in each case. A substantial amount of background information is also provided. This includes useful summaries of early jet engine activities in other countries for comparison with the British scene, an extensive list of references and several short appendices on detailed aspects. In addition, the final part of the book contains a broad concluding discussion and suggested topics for further investigation.

Mr Howard is to be congratulated for undertaking this survey and producing this book and FAST is to be congratulated for publishing it.

F W Armstrong

FREng FIMechE FRAeS

This book is the outcome of a big effort by Howard in gathering, sifting through and critically appraising a very large amount of material

Dr Wernher von Braun

(centre), then Chief of the

Guided Missile Development

Division at Redstone Arsenal,

Alabama, discusses a ‘bottle

suit’ model with Dr Heinz

Haber (left), an expert on

aviation medicine, and Willy

Ley. NASA

Dr Wernher von Braun

(centre), then Chief of the

Guided Missile Development

Division at Redstone Arsenal,

Alabama, discusses a ‘bottle

suit’ model with Dr Heinz

Haber (left), an expert on

aviation medicine, and Willy

Ley. NASA A Chesley Bonestell

painting of a spaceship on the

surface of the Moon. From:

Willy Ley The Conquest of

Space (New York: The Viking

Press. 1950).

A Chesley Bonestell

painting of a spaceship on the

surface of the Moon. From:

Willy Ley The Conquest of

Space (New York: The Viking

Press. 1950). For comparison,

only two months after Willy

Ley died, Neil Armstrong took

this picture of Buzz Aldrin,

lunar module pilot, deploying

the Early Apollo Scientific

Experiments Package

(EASEP) during the Apollo 11

extravehicular activity on the

Moon. NASA.Buss’ well-researched book describes in depth Ley’s contributions to the public understanding of space and other scientific disciplines through his books, articles, science fiction stories and the radio and TV media. It is not an easy read. There are many excerpts from Ley’s works but, at the end of the book, I still felt that I did not know much about Ley as a person or as a family man.

For comparison,

only two months after Willy

Ley died, Neil Armstrong took

this picture of Buzz Aldrin,

lunar module pilot, deploying

the Early Apollo Scientific

Experiments Package

(EASEP) during the Apollo 11

extravehicular activity on the

Moon. NASA.Buss’ well-researched book describes in depth Ley’s contributions to the public understanding of space and other scientific disciplines through his books, articles, science fiction stories and the radio and TV media. It is not an easy read. There are many excerpts from Ley’s works but, at the end of the book, I still felt that I did not know much about Ley as a person or as a family man.