Post-WW2 times saw Afghanistan firmly join Moscow’s orbit for military support – with first Russian aircraft, including MiG-17 fighters, IL-28 bombers and IL-14 with An-2 transport aircraft joining the Afghan Air Force in 1955. During the 1960s, the Afghanistan Air Force (AAF) boasted at least 100 combat aircraft with its personnel trained in the Soviet Union. In the 1970s, the AAF was bolstered with the advent of MiG-21s supersonic fighters, with the Fishbed becoming the core combat platform for the next two decades. Similarly, Soviet-supplied Mi-8s became the helicopter of choice for transport and logistic missions, due to the lack of road and railway networks in the arid terrain and the type’s high-altitude performance and rugged design. By then the chief airbases were, and presently still remain, Kabul, Jalalabad, Kandahar, Bagram and Mazar-i-Sharif. In 1973, Afghanistan saw a bloodless coup by ex-Prime Minister Mohammed Daoud Khan, which led to the fall of the monarchy but the AAF was strengthened with the fleet reaching 400 combat aircraft.

Meanwhile, post-December 1979 and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, there saw the continued growth of AAF to 500 aircraft as Moscow aimed to support its ally against the Mujahideen. This fleet mix included 230-250 fighters (90 x MiG-17s/45 x MiG-21s/60 x Su-7s) and 150 Mi-8/Mi-24 helicopters. After the Soviets retreated in 1989, power transferred from a compliant communist regime to the Taliban in 1996. During the civil war, a large number of the AAF aircraft were destroyed or damaged beyond economical repair, due to infighting between factions drastically reducing numbers and competency.

Cessna 182 at Shindand Airbase. USAF/ Senior Master Sgt. Gary J. Rihn

Cessna 182 at Shindand Airbase. USAF/ Senior Master Sgt. Gary J. Rihn

US-Western backed rebirth

The events of 9/11 and the subsequent US invasion saw the fall of the Taliban in 2001. In 2005 Afghan Air Corp (AAC) was raised through a directive by the then US Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld. Combined Air Power Transition Force (CAPTF) was the logical next plan put in motion for helicopter/transport/light-attack-based AAC for a planned number of about 200 aircraft. It comprised three air wings – one for presidential airlift, second rotary-wing and third fixed-wing operations.

By 2008, the AAC inventory included 21 rotary and 10 fixed-wing aircraft (18 Mi-17s, 3 Mi-35s, 8 An-32s, 2 L-39s). In 2009, it was comprised of less than a hundred ‘active’ pilots, hence increased human resource training was required.

Twelve years later, in December 2020, the AAF served as the primary air enabler for the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) ground forces by providing air-to-ground firepower to special operations forces and lift support to ground forces across Afghanistan.

The AAF HQ in Kabul provided command and control of 18 detachments and three wings: Kabul Air Wing; Kandahar Air Wing and Shindand Air Wing. Its aerial strike capabilities continued to improve with laser-guided munitions by A-29 Super Tucanos and Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System (APKWS) rockets by AC-208 Eliminator gunships.

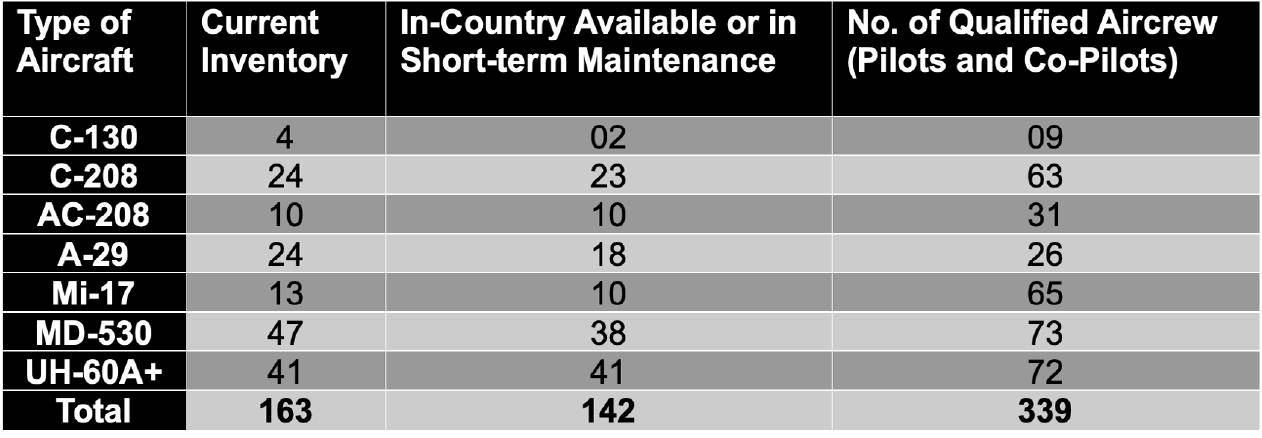

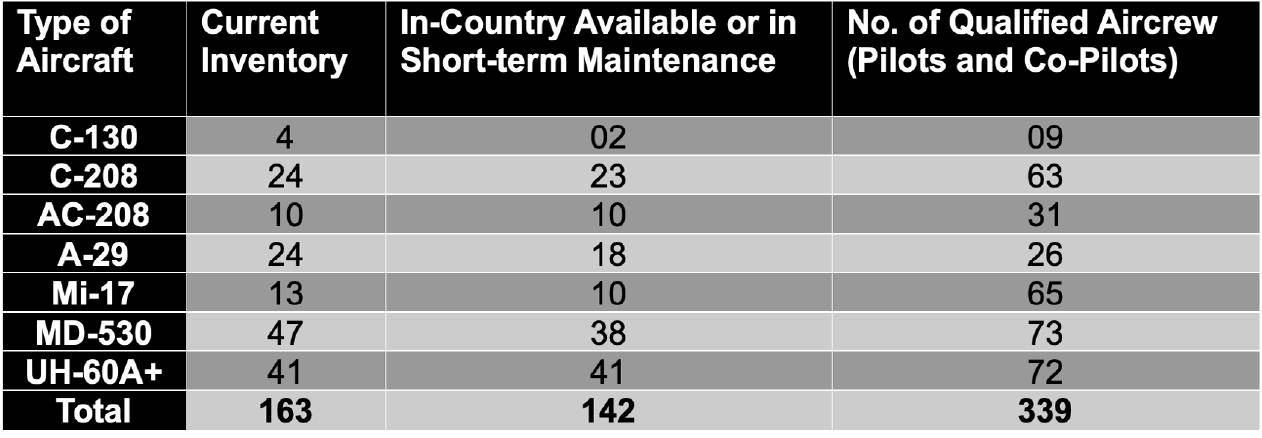

Table 1: Summary of AAF airframes and aircrews (December 2020)

Table 1: Summary of AAF airframes and aircrews (December 2020)

At this point the AAF fleet consisted of 163 aircraft. Its fixed-wing platforms included C-208s, C-130s, and A-29s; and its rotary-wing platforms included MD-530s, Mi-17s, UH-60A+s, and Mi-35 attack helicopters.

Yet, even with all this high-tech weaponry, air power had never grounded itself in the ethos and culture of Afghanistan. To bring in an American doctrinal model, training and operations and expecting it to be self-sufficient was never going to work which was what was seen in the days leading up to the exit by the US and its allies. Hardware was ready to do its job but the software (the human element) was not willing enough. After the debacle, many military experts kept saying that the ANDSF & AAF were supposed to ‘fight together with the Americans’. But the West, from day one, had never planned it that way. They were enablers of the AAF and nothing more.

The A29 Super Tucano was the primary armed COIN platform in the Afghan Air Force prior to the Taliban retaking power. USAF/438th Air Expeditionary Wing

The A29 Super Tucano was the primary armed COIN platform in the Afghan Air Force prior to the Taliban retaking power. USAF/438th Air Expeditionary Wing

Operational support

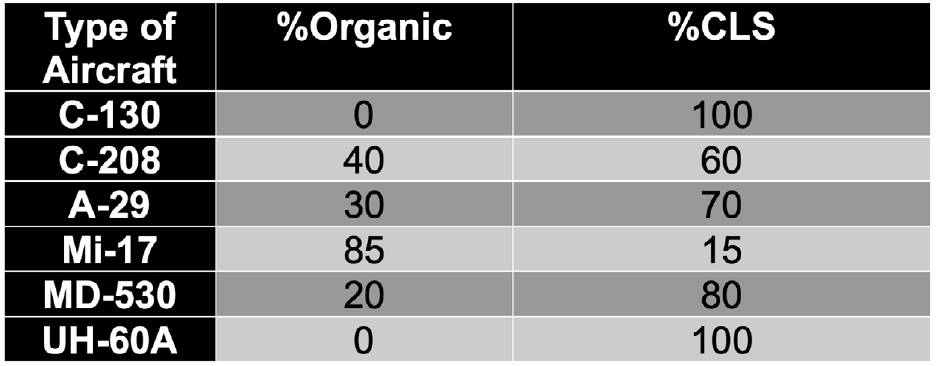

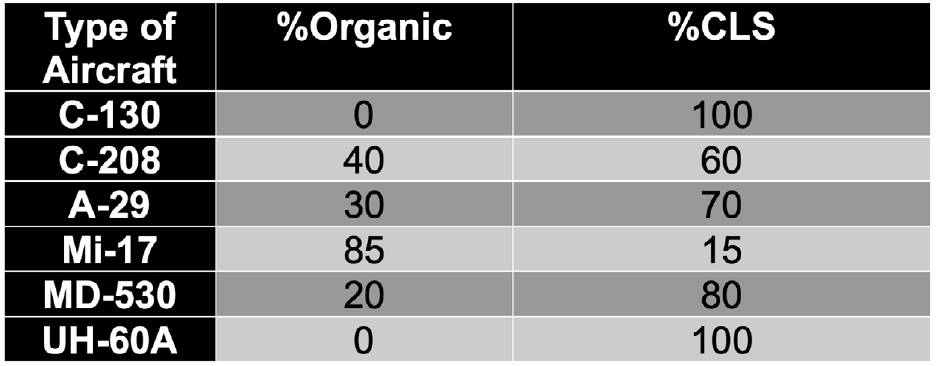

Despite the withdrawal of US Contractor Logistics Support (CLS), Kabul’s reliance on external support Table 1: Summary of AAF airframes and aircrews (December 2020) to ensure the operation of the remaining AAF fleet is likely to continue after the Taliban takeover and exit of NATO and its allies. China is most aptly placed to fill this gap as a regional player with its one-belt-one-road (OBOR)/belt-road initiative (BRI).

But without a third party, it will be challenging, even for China, to assist in the supply chain and maintenance support to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Even for the Mi-17 fleet, for which the AAF/SMW could perform 90% of flight-line maintenance, to performing overhauls every three to four years costs around $6m each. As an example, training technicians and pilots for aircraft like the C-130H, will force the AAF to look for a sustainable solution with countries which operate the Hercules. The most probable source of support is Pakistan, due to its geographic location, as well as realigned regional and national interests with China.

Table 2: Percentage of AAF organic maintenance and CLS maintenance (December 2020)

Table 2: Percentage of AAF organic maintenance and CLS maintenance (December 2020)

The final reckoning

As of 30 June 2021, just before the withdrawal of the US and its allies, the AAF had 167 available aircraft among 211 aircraft in its total inventory. As the above table shows, three of seven of the AAF’s airframes had fully usable aircraft inventories this quarter (A-29, AC-208 and C-208). In addition to the AAF’s current fleet in Afghanistan, 37 UH-60s previously purchased for the AAF were at that time held in strategic reserve in the US. Secretary Austin told Afghan President Ghani that the DoD will begin to provide these aircraft to the AAF. He added that three UH-60s would be delivered by 23 July 2021 but no further details were publicly available. Four MD-530s had also been purchased to replace battle-damaged aircraft.

Table 3: Summary of AAF airframes and aircrews on June 30, 2021

Table 3: Summary of AAF airframes and aircrews on June 30, 2021

Aerial perspective – Fall of Afghanistan

Flight from Kabul

On 16 August 2021, the situation in Kabul was deteriorating. The AAF aircrew and ANDSF personnel fled to Uzbekistan in 22 military aircraft and 24 helicopters, rather than face retribution at the hands of the Taliban. There was one mid-air collision between an Embraer EMB 314 Super Tucano/A-29 aircraft and an escorting Uzbek MiG-29 fighter jet, causing both to crash. A total of 585 Afghan soldiers arrived via aircraft and 158 more crossed the border on foot on 15 August 2021.

Tajikstan also announced on 17 August that two Afghan military Table 2: Percentage of AAF organic maintenance and CLS maintenance (December 2020) aircraft, carrying over 100 soldiers in total, landed in the Tajik city of Bokhtar. In total, 17 AAF aircraft defected over Afghanistan’s northern border to Tajikstan, including 11 Cessna 208 Caravans, 3 AC208 Combat Caravans and 3 Pilatus PC-12s.

All told, this was more than a quarter of the available AAF fleet of about 160 aircraft that defected in the final days. Most flew from Kabul but some took off from a base just across the northern border near the city of Mazar-i-Sharif, fleeing Taliban fighters who were storming the base after ground units collapsed.

The well-informed analysis relates that there were about 15 pilots who flew A-29 Super Tucano light attack aircraft, 11 pilots who flew UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters, 12 pilots who flew MD-530 helicopters and many Mi-17 helicopter pilots. Besides dozens of pilots, there were air force maintenance personnel and other Afghan security forces. Some also managed to cram family members onto aircraft.

USAF

USAF

List of aerial assets left with the Taliban

Numbers of the ‘Taliban air force’ are hazy, to say the least. During the brisk exit of the West from the main operation bases (MOBs) of Afghanistan, many assets of the AAF were rendered useless through various technical and non-technical methods. A look at photo or video evidence is the only confirmation. Meanwhile, a general amnesty for all ANDSF, announced by the Taliban reportedly collected a Table 3: Summary of AAF airframes and aircrews on June 30, 2021 decent group of maintainers for getting grounded aircraft and helicopters flyable. Thus, the amount of captured aircraft may be higher than listed but not all captured assets were airworthy. The number of aerial machines captured by the Taliban does not translate into its operational fleet. Civil aircraft are also not included in this list.

List of intact captured aircraft

Aircraft (13)

- 1 x A-29B light attack aircraft

- 1 x Cessna 208 utility aircraft

- 3 x L-39 jet trainer (inoperable for several years at time of capture)

- 8 x An-26/32 transport aircraft (inoperational for several years at time of capture)

Helicopters (45)

- 7 x UH-60A ‘Black hawk’ transport helicopters

- 11 x MD 530F attack helicopters

- 12 x Mi-8/Mi-17 transport helicopters

- 15 x Mi/24Mi-35 attack helicopters (4-15 were inoperable for several years at time of capture)

Unmanned aerial vehicles (7)

- 7 x Boeing Insitu ScanEagles

Captured but inoperable aircraft

Meanwhile, 72 aircraft were captured at Kabul International Airport but rendered useless by US forces…

Aircraft (28)

- 12 x A-29B light attack aircraft

- 12 x C-208/AC-208 utility/attack aircraft

- 3 x C-130 transport aircraft

- 1 x PC-12NG special mission aircraft

Helicopters (45)

- 12 x UH-60A ‘Black hawk’ transport helicopters

- 5 x CH-46 transport helicopters

- 14 x MD 530F attack helicopters

- 14 x Mi-8/Mi-17 transport helicopters

Summary

With the US and its allies having left the country, the million-dollar question: What is next for this new era of Afghan air power? Some Western news outlets, oblivious to the difference between operational and non-operational airframes, contributed to the perception-generation in some quarters that Washington had handed over a fully-functioning air force (plus at least one ‘fake news’ outlet spreading rumours that F-35s had been left behind). As can be seen from the above numbers, in reality, the bulk of this is helicopters, with questionable airworthiness of the rest.

Images shared on Taliban supporters social media showed fighters with Western aircraft and equipment left behind, in this case a MD 530F helicopter.

Images shared on Taliban supporters social media showed fighters with Western aircraft and equipment left behind, in this case a MD 530F helicopter.

What the Taliban is doing now, without focusing on Western or Russian tech, is cannibalising anything it can get its hands-on, making any and all possible aircraft airworthy. However, in the long run, the regime will have to find alternative sources of training and support for its much-reduced air arm.

It is likely that the Taliban will continue to ask Tajikstan and Uzbekistan to return aerial assets that escaped over the border, but this seems unlikely given the geopolitical situation.

To sustain air operations, maintenance, spares support and a supply chain will have to be established. For this, there is a requirement of a ‘decent’ amount of finance, which the Taliban currently lacks – even if the ‘black market’ might supply some spares.

The short-term plan for the ‘Taliban air force’ is to generate a bare minimum ‘counter-insurgency (COIN)’ capability against ISIS-K, while an improved transport capability will be a medium to long-term goal.

The most probable solution to regenerating some air power capability will be to look towards China for a soft-loan-based package deal. Until now regional players, especially China, have been content not to get sucked into the ‘graveyard of nations’ and play their cards from a distance.

However, with China now willing to flex both economic and military muscle in and around the region and the Afghan countryside laden with undiscovered mineral wealth valuable to the Orient, this could be a likely way forward.

Could Afghanistan one day end up operating Chinese combat aircraft and helicopters, as its new benefactor follows in the footsteps of the UK, Russia and the US?

Uzbekistan, Pakistan and other smaller countries have already extended a helping hand in regenerating aeronautical infrastructure and training in Afghanistan. For now, it is a waiting game to see which side the balance tilts.

Even said, the weapons, aircraft and equipment left behind will require a very strong supply chain and logistics support to be operational, to the degree that cannibalisation of parts will not be enough. Yet, now walks in the regional player who shares one of the shortest of borders in the world with Afghanistan, exactly 76km, which also links it with Pakistan – China. The concern that China may be overtaking the role of facilitator for this war-torn region from exiting Western powers does seem threatening at first. However, looking at this rather possibly volatile scenario with a national security and international relations lens, this is a better choice. During its first rise to power in the 1990s, the world forced the Taliban in a corner which led to a quagmire of their own making. But today, in a globalised world, no country can securely survive on its own.

Even said, the weapons, aircraft and equipment left behind will require a very strong supply chain and logistics support to be operational, to the degree that cannibalisation of parts will not be enough. Yet, now walks in the regional player who shares one of the shortest of borders in the world with Afghanistan, exactly 76km, which also links it with Pakistan – China. The concern that China may be overtaking the role of facilitator for this war-torn region from exiting Western powers does seem threatening at first. However, looking at this rather possibly volatile scenario with a national security and international relations lens, this is a better choice. During its first rise to power in the 1990s, the world forced the Taliban in a corner which led to a quagmire of their own making. But today, in a globalised world, no country can securely survive on its own.