HISTORY The R38 airship disaster

The R38 disaster 100 years on

This year sees the 100th anniversary of the disaster in which the British R38 airship crashed into the Humber estuary with the loss of 44 out of its 49 crew. BILL READ FRAeS reports on a talk given to the RAeS by Wendy Pritchard, granddaughter of R38 officer Jack Pritchard.

NAL/RAeS

NAL/RAeS

On 1 September, the RAeS presented a webinar on the centenary of the R38 disaster which featured an illustrated talk from Wendy Pritchard, granddaughter of Major J E M Pritchard who was killed in the accident.

Her talk featured both the history of the airship, together with a fascinating insight into the background of Major Pritchard and some of his colleagues. Wendy explained how the story of the R38 was intertwined with that of her grandfather, together with technical, political, organisational and personal layers. She was able to gain valuable insights from her family archive of newspaper cuttings, letters, technical papers, journals and photos, as well as a number of books.

John Edward Maddock Pritchard, known as Jack, was born in December 1889 and was a dual British and American citizen. After working as a mining engineer, Jack joined the Royal Naval Air Service in 1915 as a Flight Sub Lt where he flew submarine scout, coastal type 24 and Parseval blimps. In September 1917 he was seconded from RNAS to join the Admiralty Airship Dept as a rigid acceptance pilot trailing all new rigid airships.

Atlantic crossing

In 1919 Jack and 29 others made a double-crossing of the Atlantic in the R34. On arrival at Mineola in the US, Jack jumped out of the airship from 1,500ft and descended by parachute to supervise the ground crews. After the flight, he wrote a technical report to the Admiralty with recommendations for future airships which included a complaint that airship personnel had been controlled by a department ‘almost completely out of touch with airship requirements.’ In 1918 airship personnel were employed by the newly created RAF while the airships were owned by the Royal Navy.

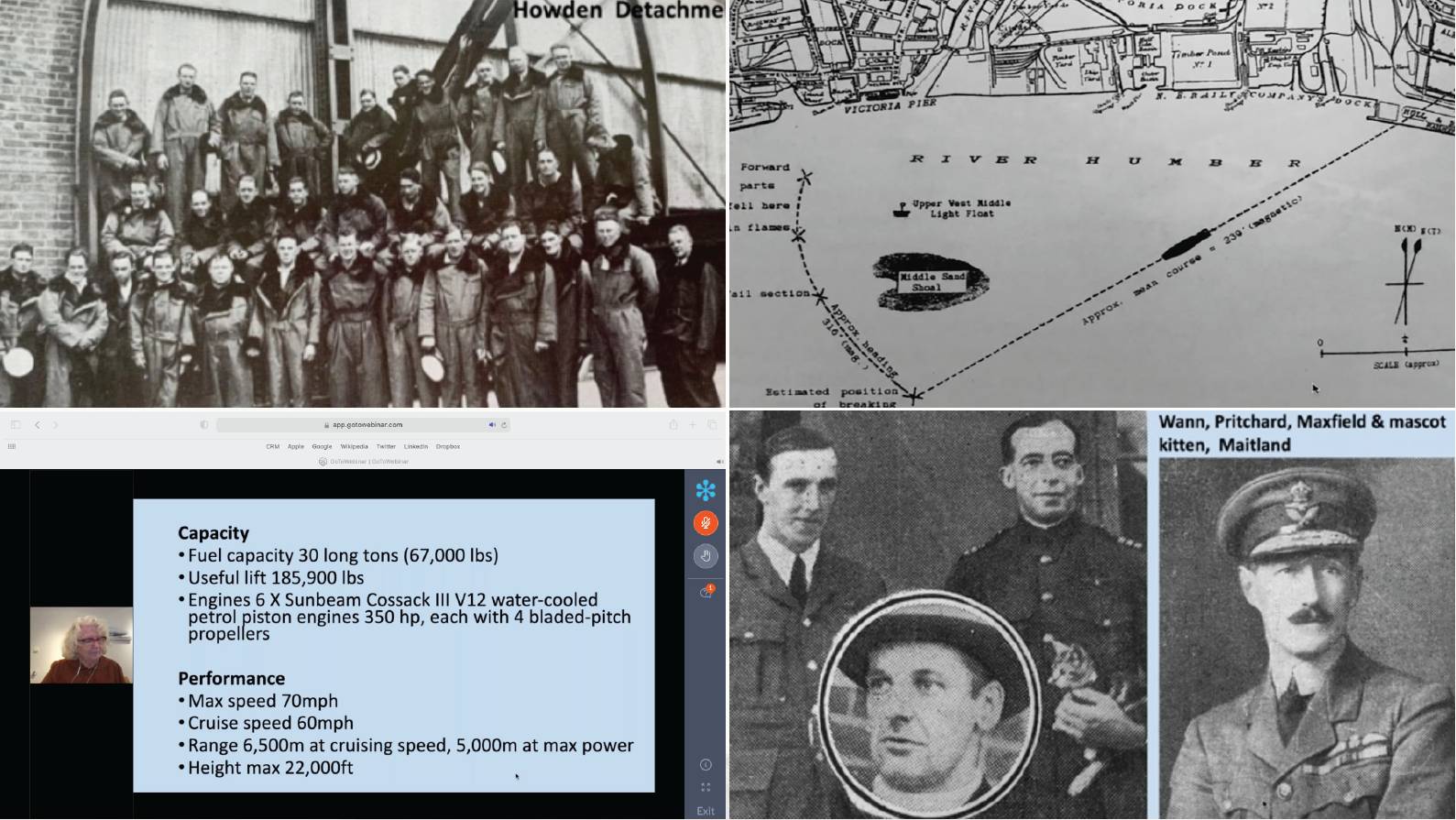

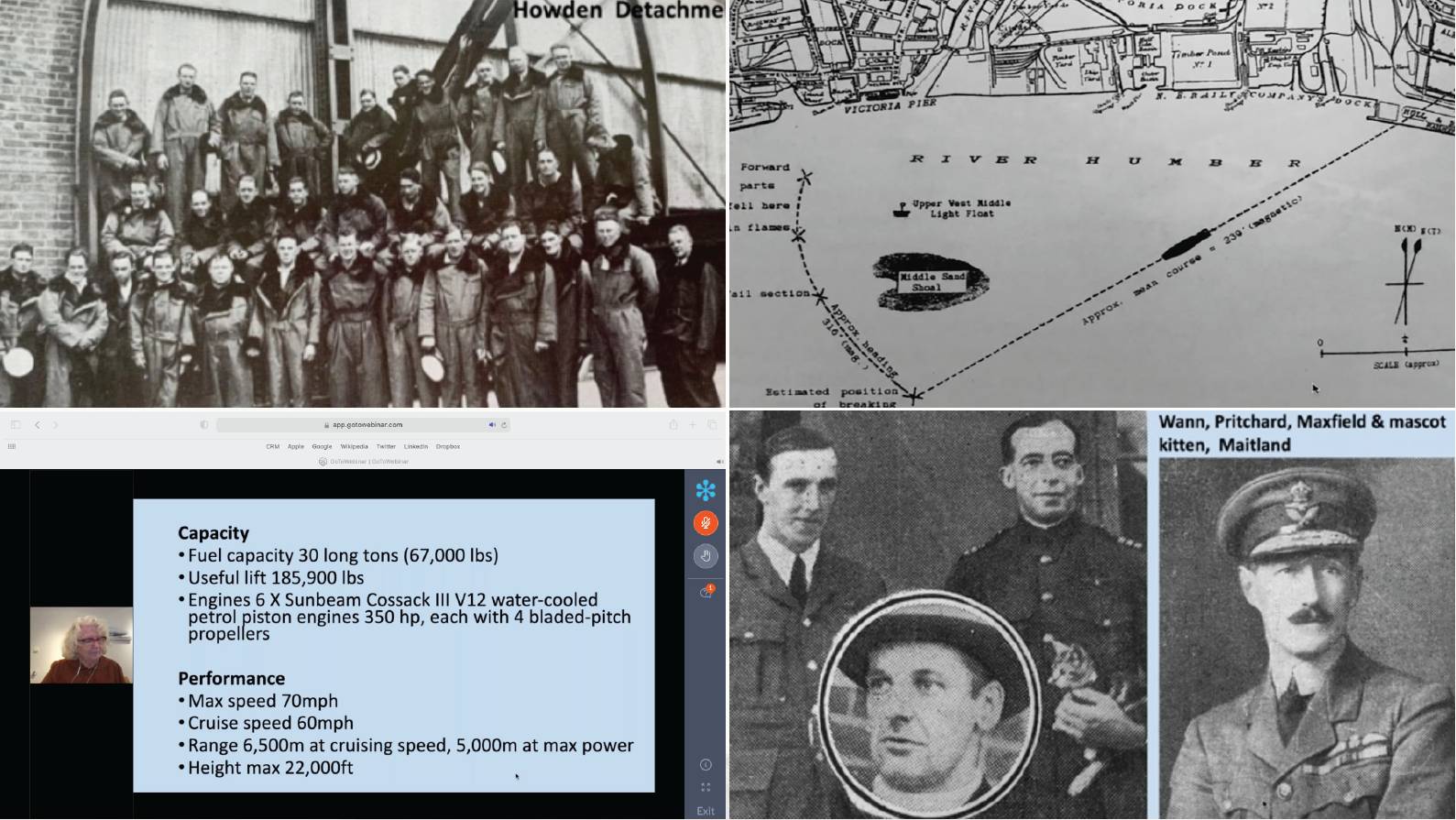

Above, clockwise from top left: The crew of the R38 at Howden, a chart of the final route of the R38 over the Humber, Key personnel of the R38 – Ft Lt Archibald Wann (left), Captain of R38 during trials before handover to US Navy; Commander Lewis Maxfield USN (holding the mascot kitten) – in charge of US Navy attachment in training at Howden and Captain for flight to US; Ft Lt Jack Pritchard (circled) – in charge of trials programme and Air Comm Edward Maitland (right) Air Ministry Director of Airships and also in charge of Howden station; technical details of the R38.

Above, clockwise from top left: The crew of the R38 at Howden, a chart of the final route of the R38 over the Humber, Key personnel of the R38 – Ft Lt Archibald Wann (left), Captain of R38 during trials before handover to US Navy; Commander Lewis Maxfield USN (holding the mascot kitten) – in charge of US Navy attachment in training at Howden and Captain for flight to US; Ft Lt Jack Pritchard (circled) – in charge of trials programme and Air Comm Edward Maitland (right) Air Ministry Director of Airships and also in charge of Howden station; technical details of the R38.

Next-generation airship

The R38 was planned as one of four next-generation rigid British airships, designed to meet new Admiralty requirements for an airship capable of patrolling for six days with a range of up to 300 miles from home base and capable of reaching altitudes of up to 22,000ft. Construction of the R38 was begun by Short Brothers in February 1919 which coincided with the company being nationalised to become the Royal Airship Works under the control of the Air Ministry, although the airship continued to be owned by the Admiralty.

Based on Zeppelin designs, the R38 was the biggest airship of the time, with a length of 695ft and a maximum speed of 70mph, powered by six 350hp Sunbeam Cossack III V12 water-cooled petrol piston engines. Because the airship had been intended for use as a war machine, the design included a number of untried features to meet Admiralty requirements, including fewer but bigger gas bags.

A total of 50 petrol tanks hung from the mainframes rather than being placed along the keel as in the R34. The two midship engine cars were positioned on the sides of the envelope to reduce the height of the airship to make it easier to get it in and out of the hangar. However, the frames were not strengthened for these engines.

However, due to post-war austerity, the airship building programme was abandoned by the British government and the R38 was the only one of the four airships to be completed, only surviving because it was sold to the US in lieu of a German zeppelin which had been destroyed before it could be taken as war reparations.

Test flights

Before the R38 (now also known as the ZR-2 by the US) was handed over to the US Navy, the R38 undertook a series of trials and test flights conducted by both British and US personnel. The project was overseen by Air Cdre Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, Director of Research and Supply at Air Ministry. Charles Campbell had responsibility for the design, manufacturing and inspection of the R38 while John Pannell from the National Physical Laboratory was in charge of making observations of the aerodynamics airships in flight.  Wendy Pritchard, granddaughter of R38 Officer, Jack Pritchard

Wendy Pritchard, granddaughter of R38 Officer, Jack Pritchard

Pritchard was in charge of the R38’s trials programme and was expected to accompany the US personnel on the airship’s flight across the Atlantic. He recommended three sets of flight trials totalling 150hr, comprising one or two short flights to test controllability and airworthiness (with an all-British crew), 100hr of graded tests at different speeds, manoeuvres and weather conditions to prove the reliability of the ship, including rough weather flying, and 50hr to be flown by USN crew – a proposal which was submitted to the Air Ministry by the Air Ministry Director of Airships, Air Comm Maitland.

However, Pritchard’s proposal was dismissed by Air Cdre Brooke-Popham who wanted the 100hr of trials to be reduced down to only 50hr. Maitland objected to this decision but was told not to voice an opinion unless he was asked.

By 20 June the Air Ministry agreed to hand over the R38 to the US before the trials were completed, on condition that they would finish trials and send the data to Britain.

On 22 June, the Foreign Office was informed by the Air Ministry that the ZR-2 could set off across the Atlantic after only 50 hours of trials.

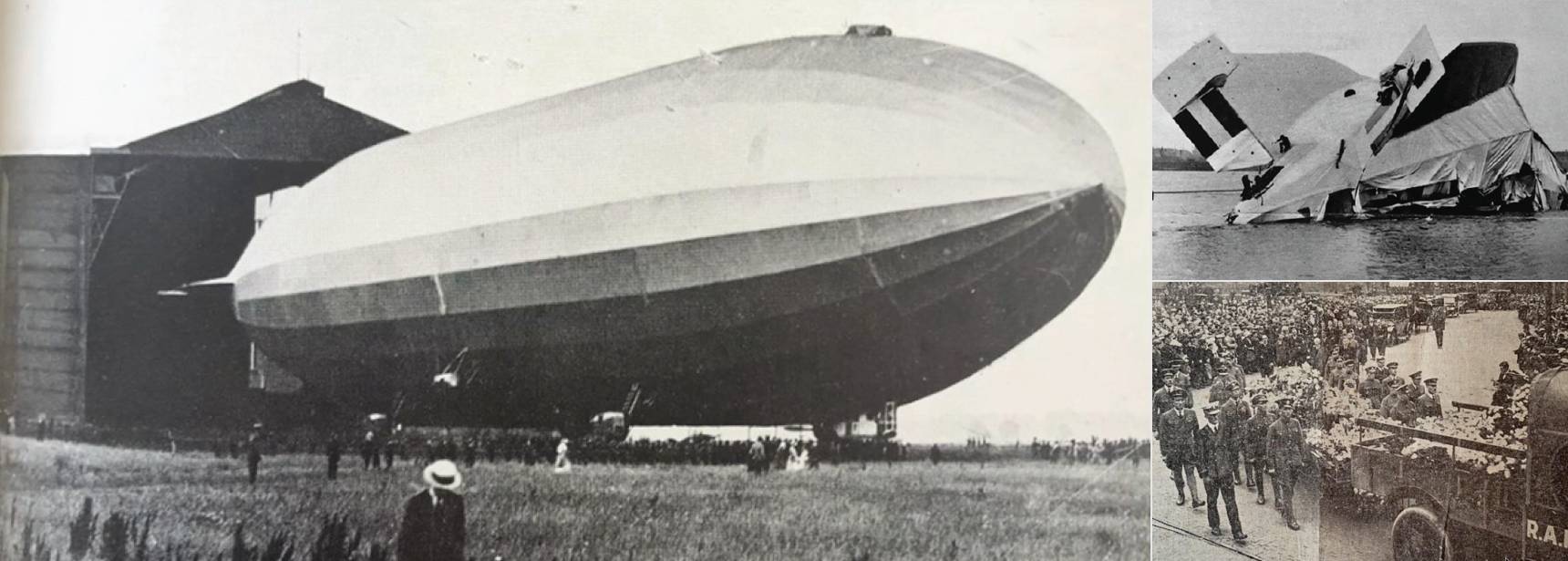

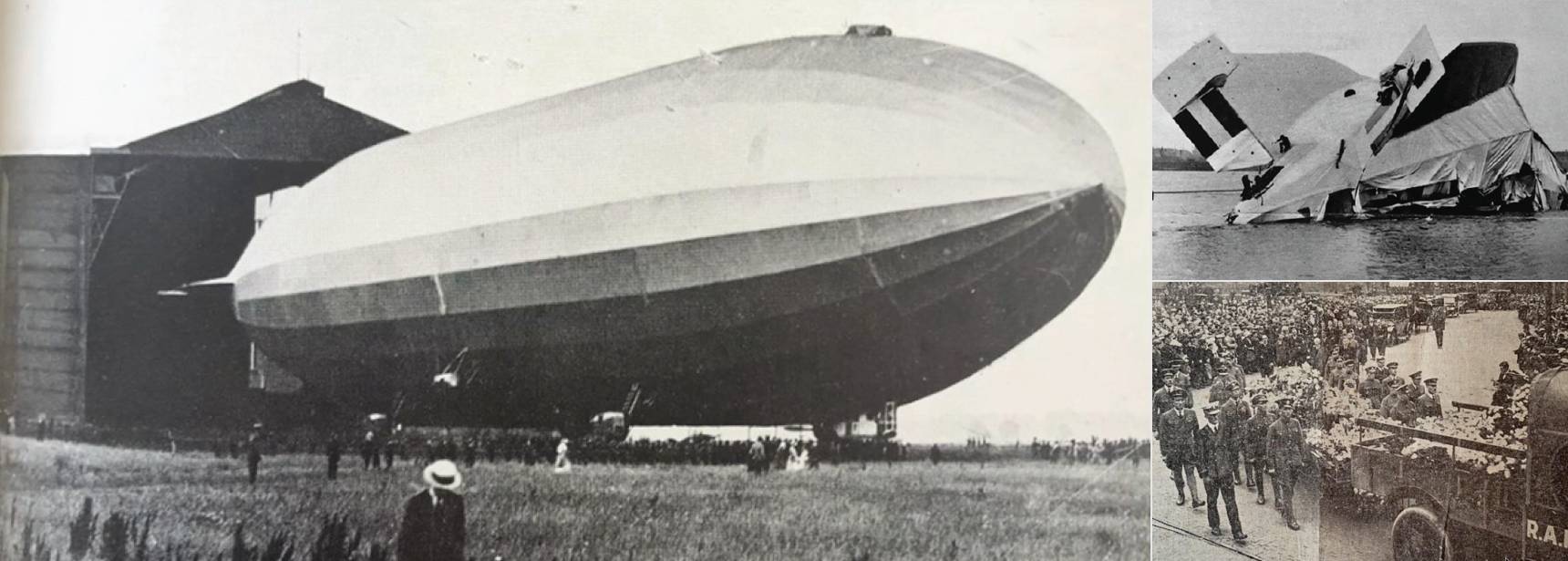

R38 preparing for its fourth flight on 23 August 1921. Near left upper: Wreckage of the tail section of the R38 showing how much of the wreckage remained above water and the stern cockpit. Near right lower: R38 funeral procession in Hull.

R38 preparing for its fourth flight on 23 August 1921. Near left upper: Wreckage of the tail section of the R38 showing how much of the wreckage remained above water and the stern cockpit. Near right lower: R38 funeral procession in Hull.

On 23 June 1921, the R38 made its first flight from Cardington in Bedfordshire to Howden in Yorkshire where the flight trials were to be made. During the seven-hour flight it was discovered that the controls were difficult to work at 38kt of speed. There were problems with overbalancing of the rudder, slackness of wires, chains slipped off sprockets and long control cables stretched. A second flight was made on 28-29 June which lasted for six hours. At speeds of up to 45kt the elevators and rudder were all found to be overbalanced and were modified on return. On 17-18 July, a third flight was made over the North Sea where the speed was increased to 50kt. In this flight airship was reported to be ‘hunting’ and veering over an arc of 500ft causing several girders in the region of the midship engines to fail and buckle. On return to Howden, Campbell ordered that the damaged girders be replaced and strengthened.

The weather in August 1921 was stormy, so there was a long delay before the R38 could make its next trial flight. On 23 August, R38 – now renamed as the ZR-2 – departed from Howden on its fourth test flight. The flight was to include tests of turns of the rudder at different speeds, after which the airship was to have returned to Pulham in Norfolk to conduct mooring mast tests. However, low cloud meant that they could not see to land at Pulham, so the crew had to spend a night at sea.

On 24 August, they conducted a full-speed trial at 60kt. The results were promising, so the airship continued flying at over 50kt at a low altitude of 2,500kt. The airship is then believed to have conducted quick changes of helm from hard over to simulate rough weather – which was a required part of the trials.

Disaster

The airship flew over Hull where, according to eyewitnesses, it appeared to be flying smoothly on an even keel but then a wrinkle appeared on the outer cover and the airship began to break in two, the nose and tail both drooping, the forward section falling faster that the aft section.

THERE WERE NO APPARENT CHECKS AND BALANCES OR LEADERSHIP CHALLENGE TO ENSURE PROPER ACCOUNTABILITY FOR THE KEY FUNCTIONS OF DESIGN, MANUFACTURE AND INSPECTION

Wendy Pritchard Granddaughter of Major J E M Pritchard

There were two explosions which knocked over people on the ground, broke glass in buildings in Hull and was heard 25 miles away. The engines stopped, flames were observed and there was a breaking sound as the airship broke in two with rapid loud explosions. Within 15 seconds the two halves had fallen into the river, the tail section landing on a shallow sandbank not far from where the breakup had occurred while the burning forward section fell close to spectators on Victoria Pier.

There were five survivors out of the 49 people on board – four of them from the stern cockpit located under the top rudder and Captain Wann who was in the control cabin. One of the crew attempted to parachute out of the stern cockpit but the ropes caught and he was caught hanging beneath the cockpit as the stern descended. However, because the stern landed on a sandbank, the surviving crew were able to jump out and were rescued within ten minutes.

The following day, Jack Pritchard’s wife Hilda was sent a telegram from the Secretary of State for Air, informing her of his death in the accident. His body, along with five others, was never found but his wallet was recovered from the river which included a return railway ticket. Of the six people highlighted by Wendy Pritchard in her talk, four were killed in the accident – Jack Pritchard, Maitland, Campbell and Pannell. The airship captain Flt Lt Wann was among the survivors while Brooke-Popham was not aboard.

On 31 August, a memorial service was held at Howden church, followed by another service in Hull Minster on 2 September to bury some of the victims. A memorial service was also held at Westminster Abbey on 7 September.

There were three enquiries – an RAF Court of Enquiry in late August, an Aeronautical Research subcommittee which investigated technical aspects of the disaster (chaired by Mervyn O’Gorman, chairman of the RAeS 1921-22) and an Admiralty Committee enquiry into the design of the R38. The court of enquiry concluded that there was a lack of vital aerodynamic information as to the effect of modifications on the strength of the structure.

The Technical Committee concluded that the R38 should have been 65% stronger than the smaller R33 but was in fact 50% weaker. The airship was not strong enough even for normal weather. The enquiries only commented on design and to some extent the organisation and did not name individuals or comment on the manufacturing or the trials.

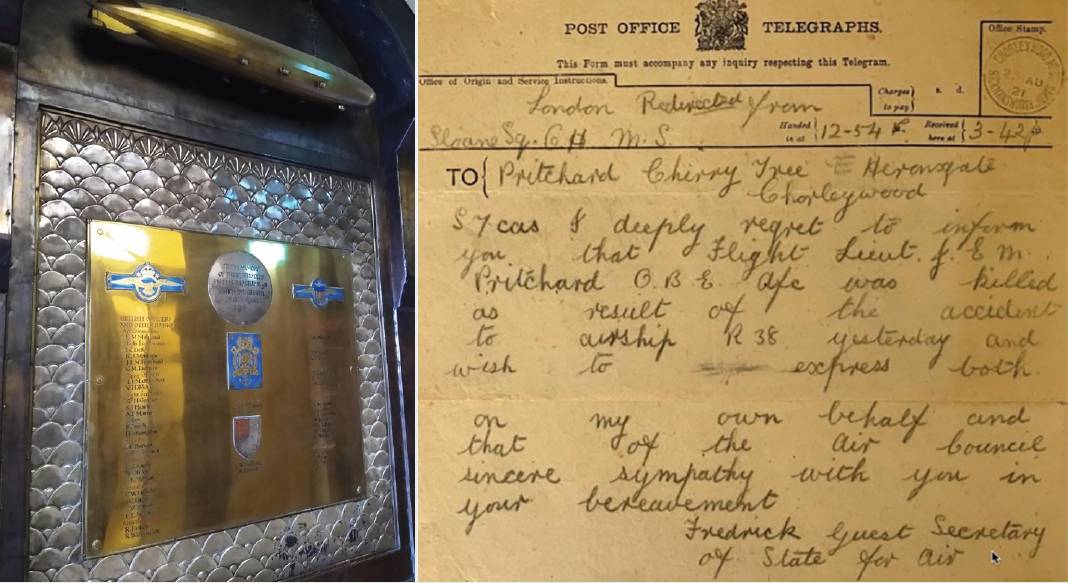

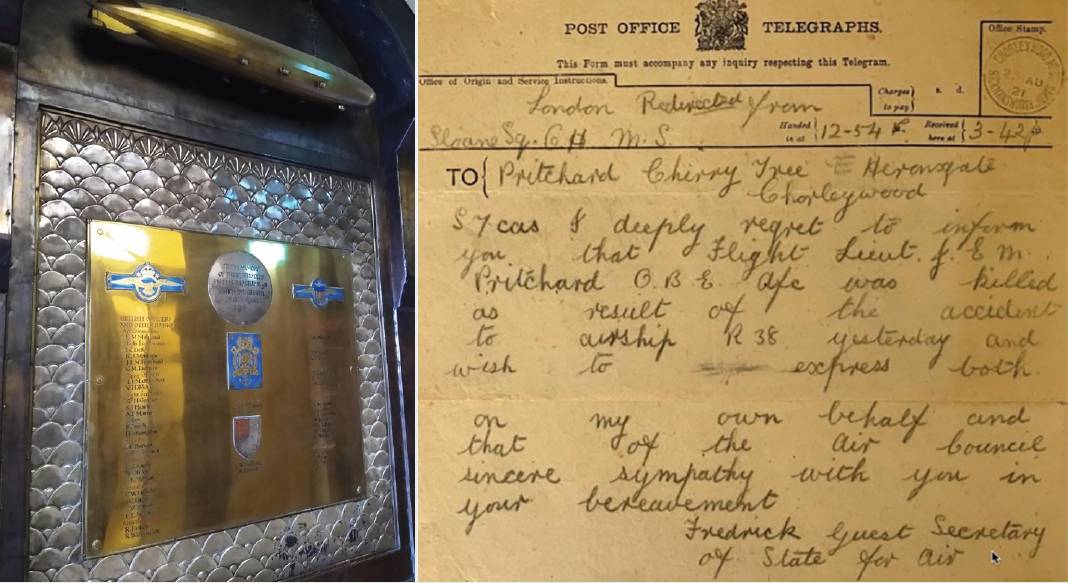

Above left: The R38 memorial at RAeS HQ, Mayfair, London. Above right: Telegraph reporting Ft Lt Pritchard’s death.

Above left: The R38 memorial at RAeS HQ, Mayfair, London. Above right: Telegraph reporting Ft Lt Pritchard’s death.

Conclusions

Wendy Pritchard ended her talk with a summary of her own conclusions as to the cause of the disaster:

- There was no examination as to whether the design was fit for purpose after the known modifications and changes of use.

- There were also changes of organisation which had an undoubted impact – a shift of airships to the Air Ministry which had effectively taken their eye off airships with a view to closing them down; compartmentalisation in which the Admiralty, the Air Ministry, the National Physical Laboratory and the Royal Airship Works did not talk to each other. For example, reports produced by the NPL were never seen by the designers or constructors.

- There were no apparent checks and balances or leadership challenge to ensure proper accountability for the key functions of design, manufacture and inspection which were all done by Campbell at the Royal Airship Works.

- There seemed to be a culture where experts could not challenge their superiors.

- Between 1921-1925 no airships were developed in UK but later airship designs learned lessons from the disaster and were built heavier and stronger.

Memorials

In 1924 Hull unveiled a memorial for the victims of the R38 disaster. Located in Hull Western Cemetery, the memorial is still extant today and was commemorated in a 100th-anniversary memorial service on 22 August 2021. There is also an R38 memorial erected in 1928 in St Mary’s church, Elloughton in East Yorkshire which commemorates Commander Maxfield and the US Navy officers.

Following the disaster, the RAeS which ‘viewed with concern the stoppage of British airship development’ decided to raise a fund with the dual purpose of providing a memorial tablet and also to ‘stimulate the continuance of interest in airship development and progress.’ In December 1922, the RAeS Aeronautical Journal announced the R38 Memorial Prize for the best technical paper on airships to be funded from the R38 Memorial Research Fund.

Designed by Mr Paul Cooper, the Royal Aeronautical Society’s memorial to the R38 was unveiled in the Society’s library at its then headquarters at 7 Albemarle Street in London by the American Ambassador on 29 June 1925. According to the July 1925 issue of The Aeronautical Journal, the event was attended by two of the crash survivors – H Bateman of the National Physical Laboratory and Corporal W A Potter, together with around 30 relatives of those who had lost their lives. Some of the crew were also reported to have been RAeS members.

The memorial was subsequently moved to the RAeS’ present HQ at No4 Hamilton Place. The RAeS memorial bears the inscription ‘To the memory of those who died in HM Airship R38 which failed and fell 24 August 1921’. The names of the victims are divided into lists of men from the RAF, USN, Institute of British Naval Architects and the National Physical Laboratory and includes the name of Jack Pritchard.

A longer version of this article can be found on Aerospace Insight.

NAL/RAeS

NAL/RAeS Above, clockwise from top left: The crew of the R38 at Howden, a chart of the final route of the R38 over the Humber, Key personnel of the R38 – Ft Lt Archibald Wann (left), Captain of R38 during trials before handover to US Navy; Commander Lewis Maxfield USN (holding the mascot kitten) – in charge of US Navy attachment in training at Howden and Captain for flight to US; Ft Lt Jack Pritchard (circled) – in charge of trials programme and Air Comm Edward Maitland (right) Air Ministry Director of Airships and also in charge of Howden station; technical details of the R38.

Above, clockwise from top left: The crew of the R38 at Howden, a chart of the final route of the R38 over the Humber, Key personnel of the R38 – Ft Lt Archibald Wann (left), Captain of R38 during trials before handover to US Navy; Commander Lewis Maxfield USN (holding the mascot kitten) – in charge of US Navy attachment in training at Howden and Captain for flight to US; Ft Lt Jack Pritchard (circled) – in charge of trials programme and Air Comm Edward Maitland (right) Air Ministry Director of Airships and also in charge of Howden station; technical details of the R38.