Book Reviews

By Graham Rood

Farnborough Air Sciences Trust, 2021, 434pp, £25 from https://fastmuseumshop.org.uk/

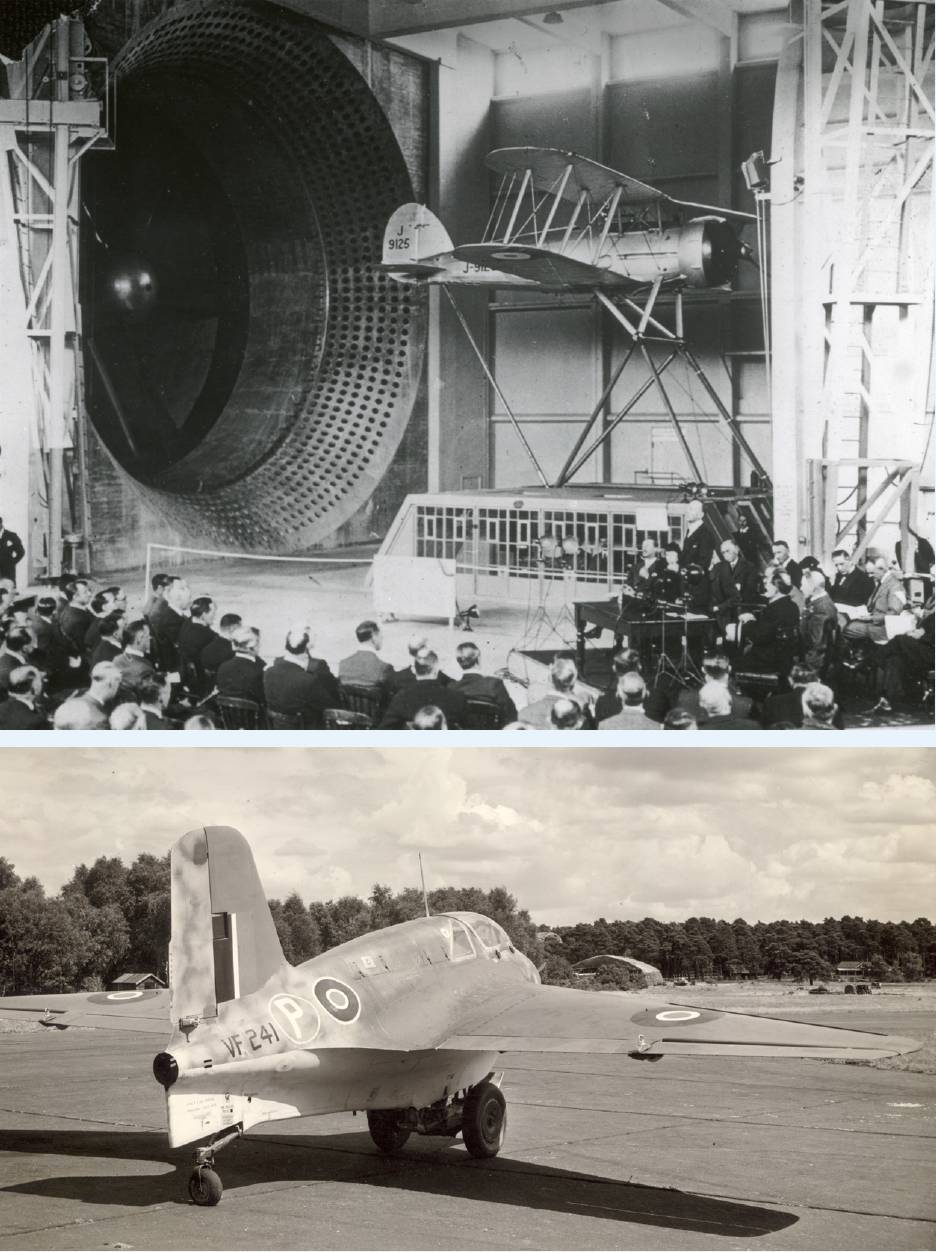

Top: Gloster SS19B, J9125, suspended in the 24 Foot Wind Tunnel at the RAE Farnborough. Above: Captured Messerschmitt Me163B-1a Komet, VF241, in RAF markings at the RAE. Both RAeS (NAL).

Top: Gloster SS19B, J9125, suspended in the 24 Foot Wind Tunnel at the RAE Farnborough. Above: Captured Messerschmitt Me163B-1a Komet, VF241, in RAF markings at the RAE. Both RAeS (NAL).

Throughout the 20th Century the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) and its predecessors, the Royal Aircraft Factory and the Army Balloon Factory, were at the forefront of innovation and the application of science to aviation. Many of the equipment, procedures, materials and techniques that the RAE developed are now taken for granted and accepted as a part of everyday life, while others played a vital role in the two world wars that were fought in the 20th century.

In this book Dr Rood, who was a scientist at Farnborough for over 40 years and is now the curator of the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust, examines the work of RAE by studying 100 objects and concepts that emanated from the work of the Establishment during its existence.

One of the early examples was the work carried out in 1916 to find the extent of the improvement in performance that would result from the use of variable pitch propellors and to investigate the mechanical difficulties that might ensue.

Between the two world wars aviation developed at an increasing pace and the RAE was at the forefront of that development. One particularly important facility constructed during that period was the large 24 Foot Wind Tunnel which dominates Farnborough airfield to this day. It was built to test full-size aircraft with their engines running. Now disused, the tunnel is preserved as a Grade 1 Listed Building which can be visited by arrangement with the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust.

During WW2, the Establishment was involved in a large number of projects vital to the war effort. The book describes many of these, including work on the introduction of VHF radios, on Airborne Interception Radar, on the Mk14 stabilised bombsight and the ground Position Indicator which were fitted to the Lancaster bomber and on the assessment of the technology and capabilities of captured enemy aircraft.

Following WW2, one topic of great interest was the operation of aircraft in bad visibility conditions. To examine this RAE set up the Blind Landing Experimental Unit, which played a major role in the worldwide development of the system that led to automatic landing of airliners becoming a routine part of civil aviation. RAE also carried out the investigation into the Comet crashes in 1954 and subsequently studied the aerodynamics and structural integrity of Concorde. Another world-leading development during this period was the invention of carbon fibre as a new lightweight high strength material which is now widely used in aerospace and other structures, including even golf clubs.

These are but a few examples of the work described in great detail by Dr Rood in this invaluable book, which includes a large number of unique photographs, together with text from original reports, that have never been published before.

This book is a ‘must have’ for anyone interested in the development of aviation in the 20th century. It is a fascinating read and you will find yourself consulting it regularly as a treasure house of aviation.

Sir Donald Spiers

HonFRAeS

Naval Institute Press (in co-operation with the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies), Annapolis MA, 2021, 305pp, £54.95.

The war against ISIS was complex at all levels from the political and strategic through the operational down to events on the ground. In this volume Ben Lambeth has sought to unravel some of the major issues surrounding the employment of air power by coalition forces from 2014 to 2019.

A 27th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron pilot disengages an F-22 Raptor from the boom of a 908th Expeditionary Air Refueling Squadron KC-10 Extender on 22 August 2017, in the skies over southwest Asia, as part of the Air Force Global Strike Task Force, members of the 27 EFS take the fight directly to ISIS. USAF photo by Senior Airman Preston Webb.

A 27th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron pilot disengages an F-22 Raptor from the boom of a 908th Expeditionary Air Refueling Squadron KC-10 Extender on 22 August 2017, in the skies over southwest Asia, as part of the Air Force Global Strike Task Force, members of the 27 EFS take the fight directly to ISIS. USAF photo by Senior Airman Preston Webb.

Lambeth is certainly well qualified to produce such an analysis; he is a non-resident senior fellow with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. He served briefly with CIA followed by 37 years with the RAND Corporation. His other works include The Unseen War: Allied Air Power and the Takedown of Saddam Hussein and NATO’s Air War for Kosovo: A Strategic and Operational Assessment (Project Air Force Series on Operation Allied Force. Lambeth is a popular and well-respected air power analyst and a regular on the air power conference circuit. As becomes very evident from some of his quotes and discussions, he is also very well connected and has close relationships, forged over his years with RAND, with many senior US Air Force officers. These include Lt Gen Dave Deptula who provides the forward to this book. He will be well known to air power scholars and practitioners alike both from his operational background, including his pivotal role in the planning of Gulf War 1 and from the conference circuit. Neither Lambeth nor Deptula mince their words.