Book Reviews

By John Sweetman

Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2019. £25.

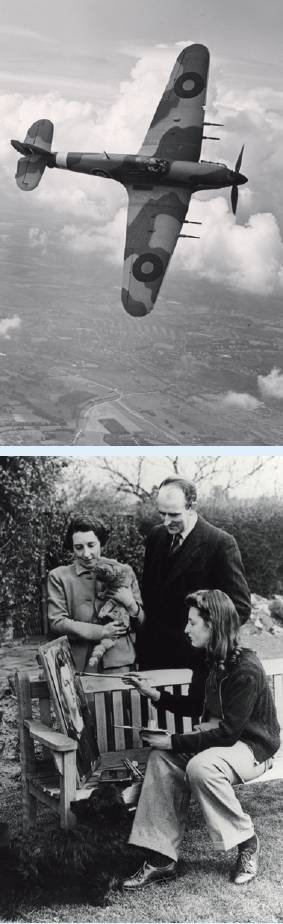

Top: Hawker Hurricane IIC, PZ865/G-AMAU, The Last of the Many!, the final production Hurricane. This aircraft remains airworthy with the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight. Above: Sydney and Hilda Camm with their daughter, Phyllis, a student at Kingston Art School in 1941. Monty and Carlo are the family dog and cat. Both RAeS (NAL).

Top: Hawker Hurricane IIC, PZ865/G-AMAU, The Last of the Many!, the final production Hurricane. This aircraft remains airworthy with the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight. Above: Sydney and Hilda Camm with their daughter, Phyllis, a student at Kingston Art School in 1941. Monty and Carlo are the family dog and cat. Both RAeS (NAL).

John Sweetman is perhaps best known for his books on bomber operations but this is a whole-life biography of one of the great fighter aircraft designers, Sydney Camm (Sir Sydney from 1953). This detailed account focuses on Camm’s interactions with the people around him, complementary to the technical aspects of his work already well reported.

In his boyhood, Camm was an avid reader of aviation magazines and, as a founder of the Windsor Model Aeroplane Club, he wrote articles for the journal Flight.

The club built a biplane glider but a powered craft project was ended with the start of WW1 when Camm moved to Brooklands as a ‘shopfloor woodworker’ with the firm that became Martinsyde. A move into the drawing office provided his first mature experience of aircraft design.

He had no formal engineering training but his ready comprehension of technical matters was shown by his first book Aeroplane Construction of 1915, which was well-received in Britain and the US. It included a section on monocoque or stressed skin construction, which Sweetman notes ‘he would resist for almost twenty years in his own work’, referring to his caution in moving on from methods that he had tried and tested.

He remained with George Handasyde until moving in 1923 to Hawkers as a draughtsman. After the Chief Designer (Wilfred) George Carter left, after an interregnum of ten months Camm was appointed to the post in 1925. Receiving strong support from one of the founders T O M Sopwith (Sir Tom from 1953), he remained with the firm in its various guises for the rest of his life.

Reports show that at work Camm was a martinet, with a quick temper accompanied by shouted ‘industrial language’, particularly if a component design seemed not to have the lowest possible weight for its duty but he was respected for his high standards and leadership.

Being basically a shy man, he was uncomfortable in company and social life in general, but he made a happy marriage. Sweetman duly records details of their daughter and granddaughter and many relatives. Examples of his ‘unobtrusive thoughtfulness’ included giving lifts to female staff and relatives in his E-type Jaguar. [This first appeared in 1961, so the earlier references should perhaps be to SS Jaguars, produced from 1936.]

The central chapters of the book deal with the evolution of the Hurricane and its operations throughout its service life. This is interwoven with extracts from contemporary Hawker archives detailing the interactions between the firm and the Air Ministry, principally by Camm in person.

The term ‘Saviour of Britain’, quoted in the title of the book, was a typical attribution in the media storm following the contribution by Hurricanes in the Battle of Britain and his award of the CBE in 1941.

Camm’s designs for potential successors for the Hurricane entered service only towards the end of the war, as the Typhoon and Tempest. His last piston-engined type was the Sea Fury, becoming the mainstay of the RN carrier force. The graceful Seahawk naval fighter was Camm’s first jet aircraft to enter service, followed by the Hunter, considered by many to have been his most elegant design.

A supersonic air-superiority fighter project had to be abandoned when the White Paper of 1957 decreed that fighters would now be replaced by missiles. However, contact with Stanley Hooker of Bristol Engines Ltd had led Camm to envisage a new aircraft concept, using the BE53 engine, developed to provide both jet lift and propulsion.

The resulting project P1127 was led by Ralph Hooper, one of the first graduate engineers that had joined the team after the war, but Camm closely followed all matters relating to design at every stage. Appointed Chief Engineer of Hawker Aircraft Ltd in 1959 and moving to ever more senior positions in the Hawker Siddeley Group, he remained at the front of representations about future projects with key Ministry and Services figures.

In the later chapters of the book Sweetman details from Hawker archives the fruitless discussions and project submissions made to promote the Harrier and derivatives, throughout which Camm showed remarkable persistence. Meanwhile, the P1127, a private venture up to the prototype stage, demonstrated the practicality of the short take-off and vertical landing (STOVL) principle, gaining widespread publicity.

With more support provided by the US and Germany, an evaluation squadron was formed, the aircraft now to be named Kestrel. Camm lived to know that this led to an order for a pre-production version for the RAF but the eventual order for the Harrier, and versions for the RN and US Marine Corps, did not come until after his death in 1966.

As a biography, the story ends at that point. There are photographs of Camm’s relatives and even one of his dog but only one each of the Hurricane and Harrier of the title.

The level of detail is notable and given the wide range of archived material consulted by Sweetman, it seems unlikely that any significant interaction in Camm’s life has been overlooked. A well-presented account, in which this reader readily became absorbed and thoroughly recommends.

Prof Brian Brinkworth

CEng FREng FRAeS